On Tuesday, the Supreme Court delivered a verdict that empowers the ordinary Indian citizen to take on the corrupt. Among other things, the court’s verdict, delivered by Justice AK Ganguly, said that any citizen of India can seek an enquiry or prosecution against people suspected of corrupt practices.

When sanction had to be sought for a prosecution from government authorities, there has to be a timeframe within which this has to be given. The court deemed three months to be adequate for sanctioning prosecution of public servants or ministers.

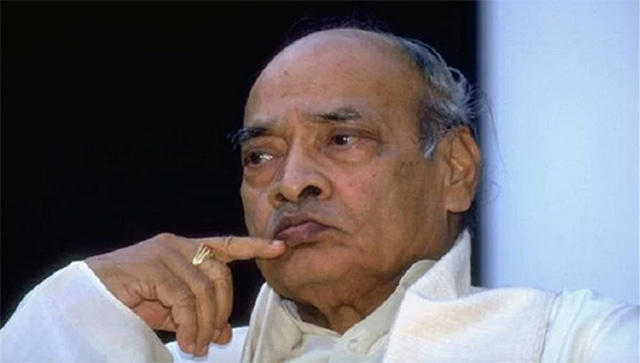

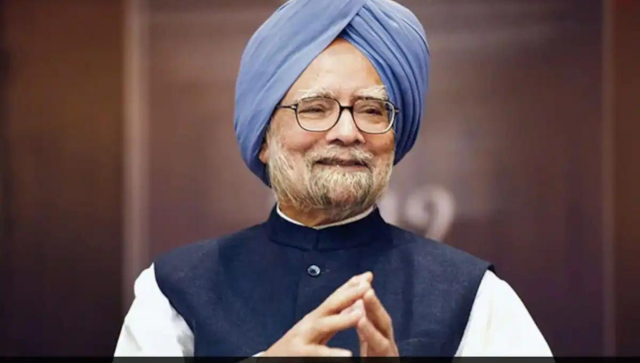

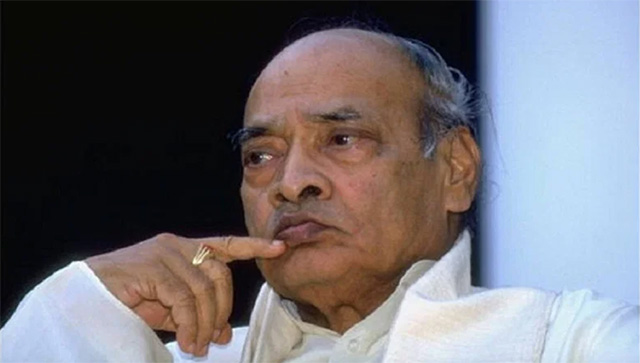

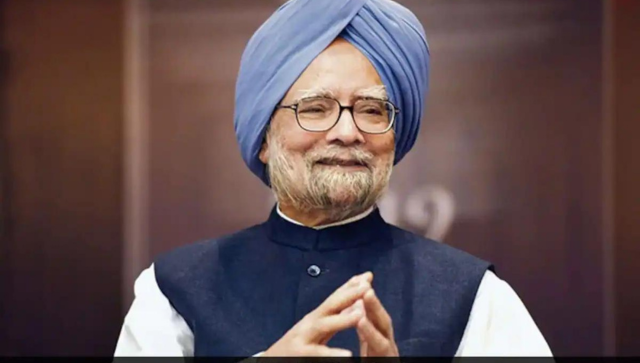

Politically, the judgment comes as a slap in the face of the UPA government, and especially Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, for the verdict is really a moral indictment of his inaction in the 2G scam.

The case was brought by maverick Janata Party chief Subramanian Swamy seeking a direction to the PM to allow the prosecution of Andimuthu Raja in the 2G spectrum scam.

The PM sat and sat on the prosecution – and this is why the court’s verdict on setting a finite timeframe for sanctions is direct indictment of his conduct in this issue.

Consider what happened.

On 29 November 2008, Swamy wrote to the PM seeking sanction to prosecute Raja for the 2G spectrum scandal.

The PM did not reply till 19 March 2010 – that’s 16 months of sitting on his hands — and when he replied he claimed that any sanction would still be “premature” since the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) was investigating the matter.

The PM has not publicly stated the reasons for his silence or his inability to sanction the prosecution of Raja, but his arrest – which happened a year later in February 2011 – suggests that Manmohan Singh’s failure to accord sanction gave the former communications minister more time to cover his tracks.

The judgment also means that governments cannot use the CBI as an argument to delay sanctions. This is the reason the PM gave to deny Swamy his right to prosecute Raja.

The Supreme Court order essentially says that the PM (or any government authority that has to accord sanction for enquiry or prosecution) has to give a decision within three months, with an additional month given in case it requires the opinion of the attorney general.

Thus, four months is the maximum time a government will have to delay corruption cases brought up by the public.

In fact, the verdict is not just a vindication for Swamy, but the entire citizenry, since it empowers anyone to chase the corrupt.

The Supreme Court order sets aside an earlier verdict of the Delhi High Court which declined to direct the PM to take a decision on prosecuting Raja. In overturning the high court, the Supreme Court said that the right to complain against a public servant under the Prevention of Corruption Act is a right under the Constitution.

However, to make the right a reality, Parliament will still have to legislate it: what happens if the government does not sanction a prosecution within four months?

The logical answer is that a new law will have to make it explicit that on the lapse of four months, sanction will automatically be deemed to have been given.

But this law will have to be drafted and passed, and till Parliament acts citizens will still have to move the courts for action in corruption cases.

Perhaps, this is the right comeback situation for Team Anna.

Watch video of the Supreme Court accepting Swamy’s plea against PMO

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)