In her prime, Zareena Begum would be carried to mehfils organised by Thakur families in a palanquin. The last singer of the courts of Awadh was accorded respect which has eluded women of her ilk, tawaifs, for ages. However, she spent the last few years of her life in sickness and destitution, an account of which Kathak dancer Manjari Chaturvedi shares hours before she is scheduled to perform at Mumbai’s Royal Opera House.

It was in Lucknow that she came face to face with Zareena again, over a decade after having first performed with her in 1999. However, this was a Zareena far from what she had remembered — there she sat on a takht in a hot, stuffy room with a sheet of tin as a makeshift roof, weakened by a stroke of paralysis. “She was flipping through a book when I asked her if I could do anything for her. She looked me in the eye and said, ‘ek baar Benarasi saree pehen kar stage par gaana hai.’” Shortly after the confession, Zareena and Manjari performed to a packed arena in Delhi, fulfilling the singer’s desire to have one final rendezvous with the stage and leaving Chaturvedi with what she describes as a mission: erasing the ambiguity of contemporary perspectives on courtesans which has relegated them to the peripheries of India’s art and culture panorama despite having kept a multitude of song and dance traditions alive.

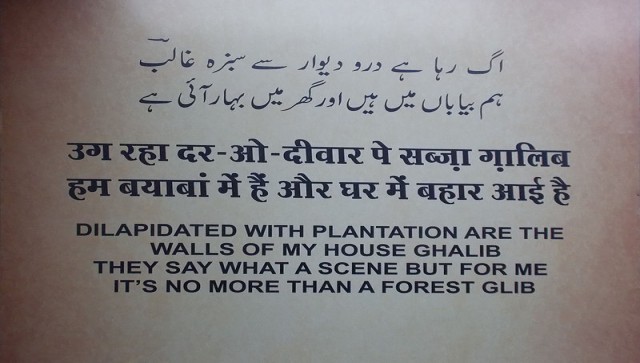

A major step in that direction is her exploration of a mystifying aspect of Mirza Asadullah Baig Khan’s life — his fondness for an unnamed courtesan. After a decade of research, Chaturvedi has put together a song and dance production, The Legend of Nawab Jaan and Mirza Ghalib, where she plays the courtesan while actor Ekant Kaul transforms into the 19th-century poet. Although multiple renditions of this relationship exist, in Chaturvedi’s production, the focus shifts to the muse who was able to inspire one of the world’s greatest literary treasures.

Chaturvedi’s Nawab Jaan isn’t an ordinary singer incidental to Ghalib’s couplets. She is a fully-realised character, imagined to re-write the narrative around tawaifs. “The women of those times were not well-read. However, it was the baijis and the tawaifs who could read and write Persian because they needed the language for their shayari. Because they were well-read, they could hold conversations on society and politics, and communicate through poetry which ultimately became their forte,” explains Chaturvedi. She refers to tawaifs as “the first actors” who ended up being sidelined because no records were made of their contribution to arts and literature. “The patriarchy did not know what to do with these women because they were ahead of their times. Therefore, they were stigmatised as ’the fallen ones’. But the truth is that they were educated women who were in control of their finances and exercised freedom — even while choosing partners.”

The Legend of Nawab Jaan and Mirza Ghalib takes place in 1857, as an old Ghalib wonders what could have been. As the story travels back into time, we are made aware of his friendship with Nawab Jaan through the material gathered from his couplets and letters. In the theatrical presentation, even though Ghalib is aware of his charm, he admits that it was her who understood him enough to make sense of his poetry, when very few could. “That is a mark of Nawab Jaan’s literary genius,” Chaturvedi adds.

Surprisingly, it is not the ‘doomed’ courtesan but the character of Ghalib that takes on an almost penitential tone as he looks back on a lost opportunity, which could have turned into a fully-developed romance. Nawab Jaan, on the other hand, is portrayed as “a tawaif with a mind of her own”. Although we see her pining for Ghalib, what sets this interpretation of her apart from the rest is that she allows herself to be vulnerable, never once dancing around the tired trope of ’the other woman’. It is this characterisation that Chaturvedi uses to address the pith and core of how tawaifs are viewed in performance art. “It is the way of the world. The art may be important, but not the muse. In this case, it is because the muse is a woman, a nachnewali," she points out.

Translating her research into commercial success has been a challenge, but Chaturvedi wants this part of history to be remembered by those who are at the forefront of the country’s arts and culture movement. “People have this misconception that I want to take Kathak back to the kotha. What is a kotha anyway? It is a performance space, like this one. We need to be able to separate our understanding of tawaifs and their profession to acknowledge their art, for which we need to bring our art forms out of the classrooms and into the real world,” says Chatuvedi while pointing at the stage she’s set to bring Nawab Jaan to life on.

Manjari Chaturvedi and Ekant Kaul performed at the Royal Opera House on 8 February, 2020.

)

)

)

)

)