“India trades up, finds census,” declares the cheery Mint headline. “Analysts say the upward material mobility creates the basis of a new consumer boom,” adds the subhead. More Indians have mobile phones, electricity, access to drinking water from taps, toilets, even banks. The demand economy is up, up, and away!

Other newspapers have been less exultant, like, say, The Hindu which prefers to belabour less pleasant aspects, like defecation: “Only 46.9 percent of the total 246.6 million households have toilet facilities. Of the rest, 3.2 percent use public toilets. And 49.8 percent ease themselves in the open. In stark contrast, 63.2 percent of the households own a telephone connection — 53.2 percent of mobile phones."

We Indians now head out to the fields, lota in one hand and our mobile in the other. A bit embarrassing, perhaps, for a wannabe superpower. But even this is merely a cultural problem according to Registrar-General and Census Commissioner C Chandramouli, who says, “Cultural and traditional reasons, and lack of education seemed to be the primary reasons for this unhygienic practice. We have to do a lot in these areas."

For all that, most seem to agree – such minor shit, aside – our “quality of life” is better than ever.

But is it? In my unexpert opinion, not really.

When I was a kid back in bad old socialist India, I couldn’t wait for my US-based relatives to come visit with their bag of precious goodies: chocolates, jeans, sneakers, cameras and VCRs. Now all I need to do is hop across to the nearest mall in Bangalore. But here’s all the stuff I can no longer do: drink water from the tap, let my kids play out in the streets, have a garden, and on really bad days, breathe the air. And I’m a privileged upper middle class Indian.

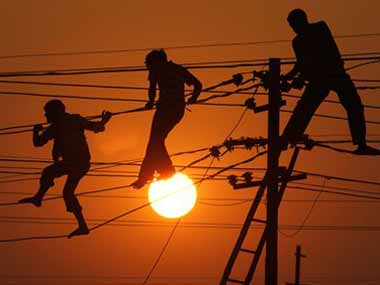

How about my maid, Bhagya, who is among the 92.7 percent of urban households who have electricity and 62 percent with access to treated tap water? She doesn’t get electricity for up to four hours a day, but that is entirely respectable compared to many others in the country. In Tamil Nadu, eight hour power cuts are routine, which is similar to crisis-stricken Andhra Pradesh.

For the average Indian, life is a bit like that Airtel commercial where the villagers have to head to the big city to charge their mobile phones. Except the big city doesn’t have much juice either. In our financial capital, Mumbai, power outages range between 6-8 hours. And never mind the escalating electricity bills that will soon make it unaffordable to turn on that aspirational air conditioner, if we can afford one.

The implications of the power crisis are, of course, far wider than a dead mobile phone. There’s the impact on industry: “Across the power sector, alarm bells are ringing, threatening to short-circuit the already unravelling growth story. Manufacturing has pulled down to its lowest in three years, export growth is petering out, while rising input costs and a significant fall in capacity utilisation across sectors have stymied hiring and investment outlook further. At least five states have declared power holidays and another eight have load-shedding plans lined up.”

Alas, our “access to electricity” is increasingly of the theoretical kind.

The other downside of the power shortage is that it exacerbates the ongoing water crisis. Lucky Bhagya does indeed have access to that much-vaunted “treated water through taps.” Too bad, those taps run mostly dry. The blessed Cauvery water graces her with its presence only once every two weeks at the height of summer, and once a week in the cooler months. It descends upon her household with divine unpredictability, early in the morning, in the middle of the night, or sometimes in the middle of the day – when she has to rush home to fill her many buckets, bottles and tubs.

According to The Wall Street Journal, “In the past 60 years, per capita availability of water, an indicator of water scarcity, has plummeted 70% in India to 1,544 cubic meters per year. (This makes India “water stressed,” a step before “water scarce,” for which the cut-off point is 1,000 cubic meters per capita).” The World Bank has long predicted that major Indian cities will run dry by 2020.

Where there is no water, there is no sanitation – whether or not there is indeed that much-disdained toilet. No wonder, people prefer shitting out in the fields. At this rate, more – not less — of us will be joining their ranks.

And as any self-respecting middle class Indian knows, when it comes to water, “potable” is a relative term. We all realise that water – be it from the rivers or the bore wells – is more unsafe than ever. So we boil, AquaGuard, even buy our ticket to safety. As for the rest, it is surely better to die of water-borne diseases or toxic chemicals that arrive in your home than to trek 20 Km for the privilege. A study by the Energy and Resources Institute and Unicef reveals that one in four children living along Delhi’s Yamuna river have more than 10 micrograms of lead in their blood. I assume they do indeed have “access” to water.

We all have more money, and therefore more stuff. But where traditional luxuries have become more affordable, basic amenities are becoming increasingly scarce. Soon we will have washing machines but no electricity or water to run them. We will have more toilets that we can’t flush. Cars and motorbikes will be increasingly too expensive to ride. Safe drinking water will likely be more expensive than a diet Coke.

Does checking a box on the census form really add up to a better ‘quality of life’? I don’t think so.

The rise of prosperity in the West was accompanied by an accompanying improvement in the environment. We don’t seem to be worried that it’s been exactly the reverse in India. Sumeet Gulati in Globe & Mail cites the Yale University’s Environmental Performance Indicators (EPI) for 2012 which rated India as having the world’s worst air: “Overall, India’s pollution ranked 125 out of 132 countries. Responding to the report, a Department of environment scientist said: ‘it is a non-issue, we have other pressing problems like poverty.’"

But how do we get rid of poverty? Condemning Indians to die of emphysema with a mobile phone in hand? Long live the consumer boom!

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)