For some inexplicable reason, the media has greeted Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) chief Mohan Bhagwat’s speeches and comments at the organisation’s three-day conclave with a mixture of

confusion

and

adoration

. This is indeed ironic considering that adherents and sympathisers of the RSS are so often wont to characterise the media as leftist and anti-Hindu. Over the three days of the ‘outreach’ programme, entitled ‘Bhavishya ka Bharat: Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh ka Drishtikon (India of the Future: A Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh Perspective)’ and held between 17 and 19 September in Delhi, Bhagwat said nothing fundamental that the RSS hasn’t been saying for decades. The only difference was the smoke and mirrors that led many sceptics to conclude that the RSS is a liberal, garden-variety nationalist institution after all. It’s an entirely different matter that he barely said anything about his organisation’s vision of a future India. But that wasn’t unusual given that he was busy defending the RSS from real and perceived slurs and repackaging his organisation to meet mainstream concerns. Let’s look at what Bhagwat actually said that is fundamental to concerns about the ‘idea’ of India and how the nation ought to be politically organised. On the first day, Bhagwat said that the RSS had an inclusive ideological framework and was

not in favour of excluding people and communities

. He also rebutted the allegation that the organisation wanted its philosophy to be hegemonic. In fact, he said, it favoured a ‘festival’ of diversity in keeping with India’s rich social, cultural, linguistic and religious plurality; the challenge facing the RSS, he said, was to be the thread that strung all the pearls together. This latter statement, with its allegorical, metaphorical ambiguity, is typically obfuscatory and perhaps contributed to Bhagwat’s celebration as a visionary liberal.

On the second day

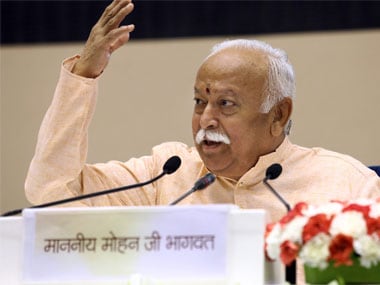

, the RSS sarsanchalak stepped into what has become over the decades the crux of disputation between the ‘secular’ and ‘communal’ versions of India. In response to the oft-levelled allegation that the RSS did not accept the Constitution as it stood, he clarified that it did, in fact, believe that the document was foundational, representing the ‘consensus’ of the country. He added that not only did the RSS accept the Constitution, it had never done anything against it. He also said, for good measure, that although the words ‘socialist’ and ‘secular’ were added to the Preamble in 1976 through a constitutional amendment, the RSS had to accept them too. Note the imperative in the locution. [caption id=“attachment_5221431” align=“alignleft” width=“380”] RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat speaks on the last day at the event titled ‘Future of Bharat: An RSS perspective’, in New Delhi. PTI[/caption] So far, so anodyne. But it did not take long for Bhagwat to give the game away. While reiterating that the RSS respected diversity, he repeated the well-worn claim that all of Indian society was Hindu society. “Some people know they are Hindus but they are not willing to accept it because of political correctness,” he said. “According to us the entire society is a Hindu society. We have no enemies, neither in the country or outside it.” Dropping an explosive paradox on the proceedings, Bhagwat then said, “We do not want to finish our enemies. We want to take them along with us.” Where exactly, if we may make so bold to ask. There was a lot more along these lines. None of it washes the slightest bit. Proceeding through the medium of densely oracular pronouncement, Bhagwat told the assemblage, “The Sangh talks of a global brotherhood. This brotherhood envisages unity in diversity. This is the tradition of Hindutva. That’s why we call it a Hindu rashtra.” There were two equally Delphic explications of these contested concepts on the concluding day, but for the moment, Bhagwat was content to defend the RSS’ unifocal resort to the idea of Hindutva by saying that while the RSS was considerate about all, its primary aim was to embrace those who accepted they were Hindus. Unity in diversity? Huh? Along the way, Bhagwat repeated some old, discredited claims: That the RSS was not political but had views on the national interest; that the idea that the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was

remote-controlled by the RSS

was untrue; and that it never asked swayamsevaks to work for a particular party, but it did ask them to support those who worked for the aforementioned national interest. What exactly ’national interest’ means or is can obviously not be taken as self-evident, and since Bhagwat did not provide any explicatory commentary, we may take it that this whole segment of the argument exists in a black hole.

On the final day

of this moderately successful public-relations exercise, Bhagwat, as we have mentioned, provided some gloss on earlier statements. None of them even remotely support the supposition that the organisation he heads is a model of liberal inclusiveness. We’ll concentrate, as we have been doing, on Bhagwat’s fundamental political and social ‘vision’. He stated again the idea that all Indians were Hindus by identity and that Hindutva was all about unity and inclusion. “The RSS is trying to unite all Hindus… All Indians are Hindus by identity. Hindutva is the balance between all religions. A Hindu’s true belief is unity,” he said, “No one is an outsider in India. Hindutva is different from Hinduism. Hindutva is about unity.” It’s difficult to decode what the last bit means. We all know that Hindutva is different from Hinduism: The former is an exclusivist, majoritarian political ideology whichever way you slice it, the latter is a religion. We’ll investigate what Bhagwat could have meant when he said Hindutva was about unity. And what Hinduism is about, in that case.

RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat speaks on the last day at the event titled ‘Future of Bharat: An RSS perspective’, in New Delhi. PTI[/caption] So far, so anodyne. But it did not take long for Bhagwat to give the game away. While reiterating that the RSS respected diversity, he repeated the well-worn claim that all of Indian society was Hindu society. “Some people know they are Hindus but they are not willing to accept it because of political correctness,” he said. “According to us the entire society is a Hindu society. We have no enemies, neither in the country or outside it.” Dropping an explosive paradox on the proceedings, Bhagwat then said, “We do not want to finish our enemies. We want to take them along with us.” Where exactly, if we may make so bold to ask. There was a lot more along these lines. None of it washes the slightest bit. Proceeding through the medium of densely oracular pronouncement, Bhagwat told the assemblage, “The Sangh talks of a global brotherhood. This brotherhood envisages unity in diversity. This is the tradition of Hindutva. That’s why we call it a Hindu rashtra.” There were two equally Delphic explications of these contested concepts on the concluding day, but for the moment, Bhagwat was content to defend the RSS’ unifocal resort to the idea of Hindutva by saying that while the RSS was considerate about all, its primary aim was to embrace those who accepted they were Hindus. Unity in diversity? Huh? Along the way, Bhagwat repeated some old, discredited claims: That the RSS was not political but had views on the national interest; that the idea that the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was

remote-controlled by the RSS

was untrue; and that it never asked swayamsevaks to work for a particular party, but it did ask them to support those who worked for the aforementioned national interest. What exactly ’national interest’ means or is can obviously not be taken as self-evident, and since Bhagwat did not provide any explicatory commentary, we may take it that this whole segment of the argument exists in a black hole.

On the final day

of this moderately successful public-relations exercise, Bhagwat, as we have mentioned, provided some gloss on earlier statements. None of them even remotely support the supposition that the organisation he heads is a model of liberal inclusiveness. We’ll concentrate, as we have been doing, on Bhagwat’s fundamental political and social ‘vision’. He stated again the idea that all Indians were Hindus by identity and that Hindutva was all about unity and inclusion. “The RSS is trying to unite all Hindus… All Indians are Hindus by identity. Hindutva is the balance between all religions. A Hindu’s true belief is unity,” he said, “No one is an outsider in India. Hindutva is different from Hinduism. Hindutva is about unity.” It’s difficult to decode what the last bit means. We all know that Hindutva is different from Hinduism: The former is an exclusivist, majoritarian political ideology whichever way you slice it, the latter is a religion. We’ll investigate what Bhagwat could have meant when he said Hindutva was about unity. And what Hinduism is about, in that case.

There is also the reiteration in the belief that India must be a Hindu rashtra. Through an equally breathtaking logical leap, this Hindu rashtra becomes the symbol of unity in diversity and global brotherhood. The unity is very visible in Bhagwat’s dissertation, but the diversity has been exorcised. Then there is the strange distinction between Hindutva and Hinduism. Hindutva is about unity, Bhagwat said. That is an admission, a wholly comprehensible one. But he also says a Hindu’s true belief is unity and that no one is a stranger in India. It doesn’t make a lot of sense unless you go back to the position that all Indians are essentially Hindu.

To buttress this outlook, Bhagwat then says that a mandir must be built at the disputed site in Ayodhya. Negotiations are possible, but the Ram Mandir Samiti will be the ultimate arbiters, not the state, nor the courts. That doesn’t seem to sit too well with the assertion made in vacuo that the RSS respects the Constitution, which represents a national consensus, and has never done anything against it. Neither, for that matter, does the opinion that cow protection is too important a matter to be ’left to laws’. Despite Bhagwat’s rhetorical bow to the sanctity of the law, when he says that matters should not be taken into one’s hands, this sounds suspiciously like an apologia for vigilantism. In other words, despite the curious outpouring of support for Bhagwat’s ’liberal’ position, what the sarsanchalak said over three days is a barely concealed reiteration of the classic, majoritarian RSS position: We are inclusive, but only when you agree to eliminate all ideas of difference and diversity. India is a Hindu rashtra in which cultural, social and religious unity is paramount. And, despite Bhagwat’s once again in vacuo claim about the RSS not wanting its ideology to be hegemonic, what he is saying is that the RSS’s ideology and vision of India — encapsulated by the term ‘Hindutva’ — must be the exclusive template for national construction. One report has said that in response to a question that there was a contradiction between his statement that Muslims are not unwanted and MS Golwalkar’s view that they were internal enemies, Bhagwat replied that the RSS recognised as valid only those elements of the RSS ideologue’s view that remain relevant. To upgrade its ideological position, it had thus replaced Bunch of Thoughts, a collection of Golwalkar’s writings with an in-house publication entitled Guruji: Vision and Mission. This has been hailed in the report as a significant public shift in the RSS’ position. Given that the question was itself misconceived — Bhagwat, as we have seen, has merely restated old RSS positions, this conclusion is unreal. Nothing is known in the public sphere about the new book — the RSS website provides no information about it and Bhagwat did not spell out what elements of Golwalkar’s thoughts have been junked to keep in sync with the times. As of now, we may treat this shift as a red herring. On the caste question, Bhagwat is, at best, equivocal. We can possibly accept that the RSS has come to accept that inter-caste integration is important, especially because caste oppression divides the Hindu ‘community’ and hurts the RSS’ attempts at majoritarian mobilisation. But it is difficult to forget that in 2015, he had mooted a review of the existing policy of reservations, making the BJP scurry for cover in an election year. The rest is mostly just window dressing. Saying the LGBTQ community must not be isolated in front of a cosmopolitan crowd, including a bevy of Bollywood stars, can’t hurt. Most of those present at the conclave, will not follow up on what RSS swayamsevaks are doing on the ground to ensure this. And on the women’s question, as we have seen, Bhagwat is as retrogressive as it is possible to be. The suggestion that all Indian men treat all women except their wives as mothers quite obviously means that only wives and mothers are worthy of respect, not women in any other category. To wind up this discussion, it may not be inappropriate to point to another curious position that many, including sections of the media, have been going on about: The failure of the Opposition to attend the conclave despite being invited. Explicitly or by suggestion, the opposition has been criticised for failing to grasp this olive branch. What olive, what branch? Why on earth should the Opposition go out of its way to legitimise a public-relations exercise mounted by an organisation that provides the mobilisational sinews to the BJP, whatever Bhagwat might say? And why should, say, the Congress or the Left parties, lend their imprimatur to a divisive, sectarian ideology they have been contesting for decades? On close examination, the RSS conclave is exposed for what it has been conceptualised as: An exercise to blunt an Opposition growing somewhat in confidence even as the ruling BJP finds itself on the back foot on a number of issues, with crucial elections around the corner.

)