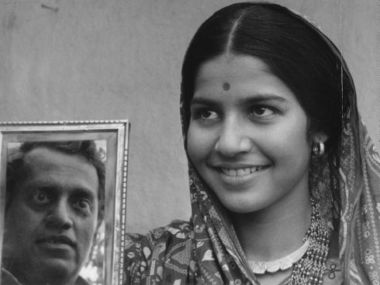

In 1969, after a long run of disappointing failures, Mrinal Sen tasted success for the first time with his first Hindi film Bhuvan Shome. With a cast and crew comprising primarily of inexperienced people, the film went on to win three National Awards, and was instrumental in cementing Sen’s position as a progressive filmmaker with rich independent thought. [caption id=“attachment_5814671” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A still from Bhuvan Shome. Twitter[/caption] The story of the film is a simple one, adapted from a short story by veteran Bengali writer Balai Chand Mukhopadhyay, who wrote under the pen-name of ‘Banaphool’. Bhuvan Shome (played by Utpal Dutt) is a strict, uncompromising, workaholic civil servant working for the Railways. Shome has shaped his entire life to serve as a model for honesty, integrity and righteous ethics, without letting emotions get the better of him. When he decides to take a break and go on a duck-hunting trip, he finds himself in an alien land in some remote and rustic corner of Saurashtra – a land where, unlike in his home ground, he is more revered as a guest than feared as a disciplinarian, thus making him equal to everyone else in more ways than one. During the hunting trip, he befriends a village belle named Gauri (Suhasini Mulay, in her debut), who leaves a rather strong impression on what had once seemed as Shome’s barren mind. His brief journey through the striking locales of a foreign land with a charming village girl seems to make him go through a transformation of sorts. Shome returns to his workplace an entirely different man. What is really striking to see in Bhuvan Shome is the way in which the subject has been treated on screen. Consider, for instance, the ending of the film, which depicts the protagonist having returned to his familiar workplace – his ‘throne’, so to speak – after a life-altering journey. Shome is now a changed man. The preceding sentence is easy to write on paper, but to portray it on screen using conventional cinematic norms would have been a mere caricature of Victorian values and principles. What Sen does, instead, is to call upon an old life-altering moment of epiphany from his own life, and asks his leading man to portray that on screen. The outcome is several precious minutes of cinematic brilliance, with the hard-boiled civil servant giving way to his inner child – right there, in front of our eyes. Sen takes the term ‘transformation’ in its most elemental, its most literal sense and places it before us sans any ornamentation at all. And in doing so, he taught us a valuable lesson in cinema – that with the right actor and the right crew, even the ordinary can be made to look beautiful on screen, and that – more often than not – it is the ordinary, instead of the extraordinary, that works in the film medium, simply because it is relatable. What that final scene also tells us is the absolute truth that no matter how many transformational journeys we go though, the world around us does not change. What changes is the way we look at that same old world. In an elaborate essay written in response to the instant popularity of the film, eminent filmmaker Satyajit Ray had famously attributed the success of the film to the undeserving glorification of a style of filmmaking that audiences found mystical, as opposed to the love one showers upon a film thanks – first and foremost – to the joys of comprehension. Ray argued that in the garb of what was being branded as the ‘new wave’ of cinema, Bhuvan Shome was old wine in a new bottle, for all practical purposes, and that it employed – among other things – most of the popular, crowd-pleasing tropes of conventional cinema, albeit repackaged to come across as a novel offering. Sen offered his retort, and this led to what is now widely known as a bit of a tension between two masters of cinema in this country. Ray was, of course, entitled to his thoughts and opinions about the film, and Sen to his defense. But one thing is sure, and pretty obvious to admirers of both legends, sometimes to humorous effect. There is no denying the fact that like two little children, Mrinal Sen and Satyajit Ray, both drew from each other – minute nuances, easy-to-miss notions, an idea here, a clever little filmmaking trick there. So, while there is a bit of Charulata in the swinging scene of Bhuvan Shome, there’ is a bit of Bhuvan Shome in the narration and animation scenes of Shatranj Ke Khilari. But that is alright and all fair, because as they say – all great minds think alike.

Mrinal Sen showed no matter how many transformational journeys we go though, the world around us does not change. What changes is the way we look at that same old world.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)