The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India’s (Trai’s) recommendations on media ownership need to be thrown into the nearest dustbin. Even assuming they are well-intentioned, and meant to create a free and fair media, they are premised on the wrong assumptions and will end up achieving the opposite: a less free, non-transparent and unviable media.

Barring the recommendations for having an independent media regulator and putting in place some checks to prevent the dominance of one media group across platforms (TV and print), the rest of the principal recommendations are a complete waste of time. For the most part, the recommendations are unimplementable, undemocratic and unbalanced. They also suggest a paternalistic mindset where unwary media consumers need protection from rapacious vested interests.

Moreover, if we were to implement Trai’s suggestions in toto, in letter and spirit, half of today’s media organisations - which fall exactly into the categories Trai wants to ban - would have to be shut.

Consider what Trai Chairman Rahul Khullar said yesterday (12 August) while releasing his report. “Ownership is a huge concern… how do you know that a TV channel operated out of Bhopal owned by a local MLA or MP is conveying the truth rather than a tinted version of the truth?”

The counter-question: how do we know a media house not owned by a politician is telling the truth too? We will know that only over time - as we match news reports with reality. This is how consumers will learn to discriminate against a newspaper published by a political party which may be telling lies.

On corporate ownership, Khullar asked: “To what extent the editorial is actually independent and how thin is the line between the newsroom and the boardroom? Second problem with media corporate ownership is this business of advertorials, private treaties… I am sorry to say it has reached scandalous position… You cannot carry on by passing out advertisements as news.”

The counter-question: Does non-ownership of media houses prevent a corporate house from influencing it? Is the advertising rupee, or indirect benefits to media editors, any less influential in the media?

The unstated premises on which the recommendations are built are these: that ownership is the reason for bias and partisanship, that bias and neutrality can and should be avoided, that restricting commercial, political and religious organisations from running news media is somehow good for a healthy democracy, and so on. There is a presumption that the entry of these interests is bad for media freedom.

All the premises are flawed. To explain why, let’s start with the opposite case. Let’s say I start a media company with my own resources, using no corporate money, religious funding, government or political support. Can I declare myself free from collateral motives? Or claim to be neutral and unbiased?

You may say yes, but think: every free blogging site is created precisely on this foundation of no commercial interest. And few people think bloggers are unbiased.

Clearly, bias is not the problem. Nor is neutrality - which means disinterest in the actual content of a report - a great virtue. In fact, the only requirement of any media owner should be the declaration of his interests openly. If Network18 is owned by the Reliance Group, this fact should not be hidden. And so on. If Ganashakti is run by the Communist Party of India (Marxist), and if Saamna is run by the Shiv Sena, these facts should be up there with the title of the newspaper. Nothing more is required. Bias is immaterial if stated upfront.

Even assuming we have a newspaper or website funded by, say, a public trust, why should one assume it has no biases? Is The Economist magazine unbiased when it has a worldview that rubbishes all counter-views? I have often found its views semi-racist and patronising. For that matter, is our national media unbiased about, say, Pakistan or our neighbours? Or is neutrality relevant only when the subject is not Pakistan?

Or take the large newspapers of yesteryears, where there were strong walls separating editors from ad space sellers and commercial interests. Did we have neutral editors then? Editors were powerful people who were courted by other powerful people. How free were those newspapers then when they wrote nothing controversial? We are not talking bribery or corruption, but did those newspapers reflect any views beyond those of their editors? Would a sub-editor with contrarian views have gotten equal space with the editor he disagrees with? Is media freedom only for the editors or also for the rest?

Point one: Bias and neutrality cannot be eliminated by any system. It is embedded in individual editors and media persons as much as in the institutions that own them. The best one can achieve is transparency in declaring one’s interests and biases. This is what ownership rules should focus on.

Next, consider the effort to exclude corporate, religious and political interests in media ownership. Given the growing non-viability of media, a lot of corporate money has come in to support news media. Network18, which publishes Firstpost and several digital and TV news platforms, is owned by the Reliance group. The corporate money came in as the group needed a financial bailout.

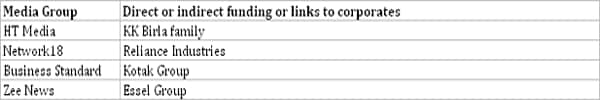

Similarly, the Ananda Bazar Patrika group sold Business Standard to Uday Kotak when it could not afford to finance this daily. The Birla group has historically run the Hindustan Times group, and now has stakes in the India Today group’s media empire. Politicians run several newspapers all over the country, and so do religious organisations or social groups. (See accompanying list of who owns whom, and the links of media to corporate or political parties).

Point two: If big media is anyway becoming unviable, how is restricting funding from new sources going to do it any good? Will neutral media be run by starving journalists?

Then, let’s come to freedom. Is ownership more important than freedom? If freedom to propagate a religion is a constitutional right, then curbing a church group or religious organisation from running television channels could be challenged as an attack on religious freedom. Of course, religious broadcasts may not be curbed, but a channel like Fox News, which is a Christian, Right-wing propagandist channel, can theoretically be banned under Trai guidelines. If it cannot, the recommendations are pointless. If it can, it is against freedom of speech.

To be sure, governments can legislate anything, but legislating the Trai recommendations would mean making something unimplementable the law of the land. We will all be living in sin, but no one will get caught.

Take TV. In an era of DTH and pay channels, who can stop any media group from broadcasting to India from a neighbouring country or even from the US? In the digital age, where text, photographs, voice and video can be uploaded from anywhere, can government really prevent me from launching a corporate-sponsored news website from Mauritius? Or Maldives? Any news organisation, however it is funded, can now publish from anywhere. So what is the point of privileging one kind of media ownership over another? If corporates want to run media houses, they will do so, Trai or no Trai.

And can any ban - on religious, political or corporate interests - even be policed? A newspaper called Sakal in Marathi is alleged to be run by Sharad Pawar. But it is his brother who actually runs it. Is this a politically-run newspaper, and hence worthy of Trai’s ban, or does it escape by being run by a politician’s brother? Is Sun TV, which is owned by the brother of former DMK cabinet minister Dayanidhi Maran, a political channel or neutral?

Or take corporate interests. If Hindustan Unilever wants to run a TV channel to promote its products, and offers news as an additional offering to attract more viewers, is this banned? Why should it be? What if it is called Unilever News and makes no bones about its corporate linkage? What’s so criminal about it?

Point three: Trai’s recommendations will have the unhealthy effect of pushing straightforward ownership of the media into surrogacy or benami holdings. This is a move away from transparency, not towards it. Trai will push more ownership issues underground.

Then there is the question of cross-media ownership. Trai wants to prevent media houses from being dominant in both TV and print. While this may have been relevant in the age when these media were dominant and could influence public opinion unduly, in five years’ time, when broadband penetrates most of the world, including India’s small towns and villages, anyone with a phone, camera or basic equipment can upload news and stuff anywhere. Print and TV will be less dominant in media and news dissemination will be fragmented and multi-sourced.

Did Narendra Modi get his message across by having friendly TV and print access? He completely bypassed them and still got his message across. In the end, it was the mainstream media that went around asking for sound-bytes from him. Even without cross-media restrictions, no one can stop a message from getting across today.

While there may be some merit to restricting excessive market share concentration in media, this aspect should be dealt with in the Competition Commission of India on grounds of monopoly power. Trying to restrict media ownership and cross-holdings is not of much help.

Point four: The issue is competition. This is what should be facilitated, not restrictions on current ownership or market shares, which may anyway start falling in the internet age. By trying to keep people out, Trai is actually ensuring that all media ownership will get more concentrated. It is reducing competition in the news space.

The last point is one of locus standi. What is Trai’s locus standi in making recommendations in areas outside telecom? Is Trai a telecom regulator or media regulator?

Trai exceeded its brief on media regulations. But even if it had jurisdiction, it recommendations are not fit for serious consideration. It is on the wrong side of change.

)

)

)

)

)