New York: The blighted poor still roam the streets of India and China, but an all-out obsession with lifestyle has a cash-rich generation flocking to spas, restaurants, movie theatres, and spending on everything from cars to appliances.

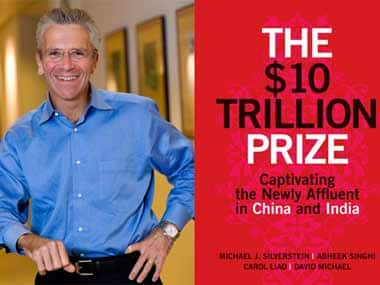

Consumers in India and China are the new kings of the global economy, Michael J. Silverstein, Carol Liao, David Michael, and Abheek Singhi, point out in their new book, “The $10 Trillion Prize.”

China and India are in the thick of a revolution in growth - not unlike the US economy in its early days - and volatility is part of the bargain. But both countries are on track to have 1 billion middle-class consumers by 2020 whose annual spending will reach $10 trillion, says the stats-filled book.

The authors, who work for the Boston Consulting Group, have calculated that between 2010 and 2020, Chinese and Indian consumers will spend $64 trillion on goods and services.

[caption id=“attachment_608392” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

The book predicts a jump in spending by Indian and Chinese consumers.[/caption]

The book predicts a jump in spending by Indian and Chinese consumers.[/caption]

Chinese consumers will spend approximately $41.5 trillion, with annual expenditures reaching over $6 trillion in 2020. Indians will spend $22.5 trillion, with annual spending hitting an estimated $3.6 trillion by 2020. Combined, they will be spending $10 trillion per year by 2020, more than three times what they spent in 2010.

Following recent dips in GDP growth in China and India, many are asking: Have the two countries lost their way? Is China a bubble about to burst? Are India’s bureaucracy, corruption and creaky infrastructure impossible?

Impact Shorts

More ShortsThe answer is simple. The authors believe China and India show the kind of unbridled optimism that used to be the hallmark of America. Many Chinese and Indian entrepreneurs expect their companies to grow by factors of 10 over the next decade.

“Risk and volatility are part of the bargain. We remain convinced that by the end of this decade, there will be 1 billion middle-class consumers in China and India and both countries will have delivered long-term annual growth averaging 8 percent,” says Silverstein.

The accelerator mindset

“The $10 Trillion Prize” says entrepreneurs in China and India display an “accelerator mindset.” They talk of their “ten-by-ten” strategy, tenfold growth in the next 10 years. Their outlook is marked by huge ambitions, a big-picture vision, and no limits on opportunities. They describe themselves as “Ph.D.’s” - “poor, hungry and driven.”

The book notes that companies like Tata, Lenovo, Huawei Technologies, Reliance Industries and the Godrej Group have set their sights not only on home-market dominance but on cracking open Western markets.

“As these leaders take their companies global, they are taking their mindset with them and it could be their most enduring export,” says the book. “Ambitious, audacious, adaptive, aggressive when necessary - these business leaders have what we call the accelerator mindset.”

The authors lament that Western firms are hard-wired to follow “tightly defined rules.” Their corporate strategy hinges on earning the cost of capital, growing at a higher rate than the overall market, and pruning poorly performing businesses. With Wall Street analysts ready to applaud CEOs for meeting their targets or pulverize them for a one percent share miss, there is often little opportunity to change course.

On the other hand, Indian and Chinese CEOs, think about strategy in a strikingly different way. They recognize that traditional return-on-investment calculations are not always relevant. They believe that when growth is this dynamic you need to be faster, more creative, and willing to learn as you go. For them, value creation rests on confidence and comfort with ambiguity, backed up by investment, talent, and fast cycles - not on preprogrammed business plans and projections to two decimal places.

“These entrepreneurs are unlike their Western counterparts,” says Silverstein.

“They don’t feel beholden to anyone and are not bound by textbook business rules. They are natural risk-takers. They focus on execution, they’re not afraid of mistakes. They believe instead that they can grow past their mistakes thanks to the rising tide of demand. These qualities make them highly unpredictable and formidable competitors.”

Godrej’s chairman Adi Godrej first defined the “ten-by-ten vision,” by creating new markets through innovative partnerships with Western appliance-makers. Its tiny ‘Chotukool’ refrigerator broke new ground by tapping rural customers with unreliable electricity.

The book also provides an insight into Chinese telecom giant Huawei Technologies chairman Ren Zhingfei, an army veteran who leads his “pack” with a “wolf spirit,” allowing them to “swarm the market” with a huge service staff. He applies Maoist principles to management, emphasizing a “rural-first” strategy, promoting self-criticism, combining theory and practice by rotating managers upwards and downwards.

“What sets the leaders of these companies apart is their extraordinary inventiveness, an enormous capacity for industry, and exceptional willpower. They really do not take ’no’ for an answer,” Silverstein says.

Paisa Vasool

The book shows Indian and Chinese consumers are in love with the idea of ‘paisa vasool’ or value for money. It’s a penchant for frugality that characterizes most Asians.

[caption id=“attachment_608397” align=“alignright” width=“380”]

Asian consumers seek more value for money in the products they buy. Reuters[/caption]

Asian consumers seek more value for money in the products they buy. Reuters[/caption]

“The Indian consumer is not like any consumer. They want Western technologies, features and Indian cost,” says Pawan Goenka, president of Mahindra & Mahindra’s auto and farm equipment business.

The book tells companies to take a leaf out of Mahindra & Mahindra which built India’s first fuel-efficient SUV. At a time of soaring gas prices, Mahindra’s competitively-priced diesel vehicles are going to have one big thing in their favor: superior fuel economy. India’s $4.5 billion sports utility and tractor-maker has consistently beaten analyst estimates by selling its Scorpio SUVs and tractors to export markets.

Mahindra & Mahindra is 64-years-old and entered the car business in 1949 by building Willys Jeeps in India. In an interview with Business India, chairman Anand G. Mahindra said of his global truck and SUV strategy: “We want to be the next Land Rover.”

Ironically, many analysts said India’s Tata Motors, was making an expensive mistake when it acquired Jaguar Land Rover from Ford Motor for $2.3 billion in June 2008. Five years after being bought by Tata, the iconic but somewhat faded British brand is regaining some of its lost luster, racking up big sales from Shanghai to London.

)