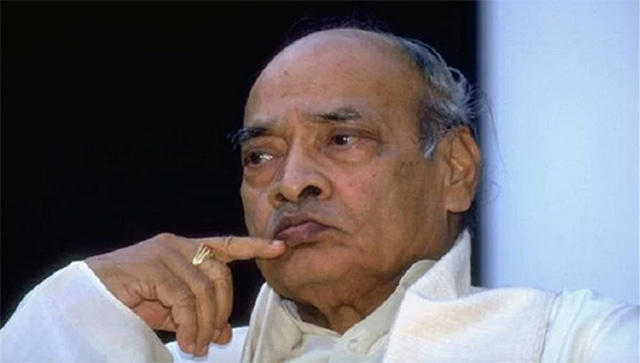

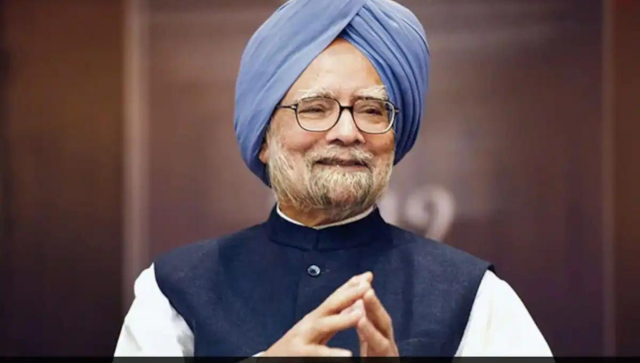

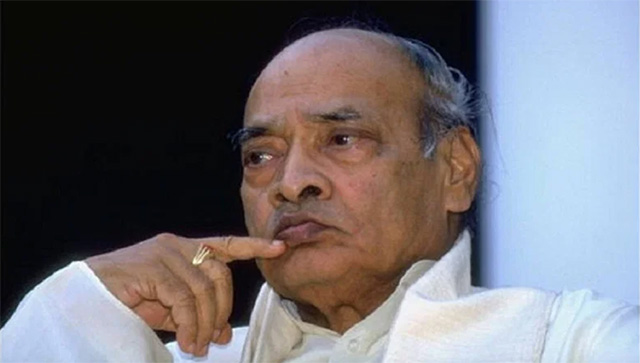

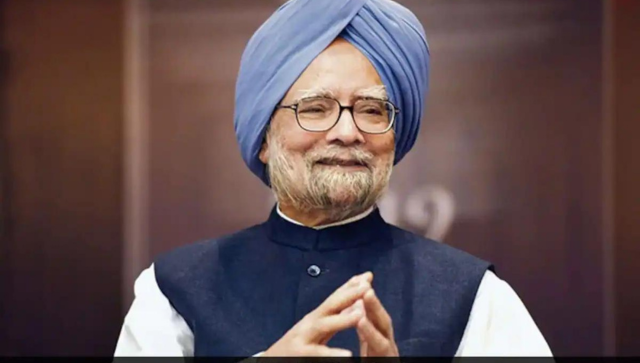

Manmohan Singh is a quiet man. He speaks sometimes in Parliament, rarely at public meetings or to the Indian media, except when absolutely required. This remarkable reticence has become a source of public exasperation, even a Twitter campaign, in recent months.

On Wednesday, the media-fuelled crescendo finally culminated in a meeting with five newspaper editors, the first of a newly instituted weekly media powwow. And his answers to all our pressing questions were, er, unsurprising: yes, he’s in command; of course, he is listening to civil society; no, he won’t commit to anything specific on anything; and as for the Marans/DMK, ah well, c’est la vie.

The behind-the-doors meeting with select editors did not unfortunately earn Mr. Singh any kudos. “A boys club meeting with editors is hardly the way to reach out to the nation. Shame!” tweeted CNN-IBN’s Sagarika Ghose. And while his comments were widely reported, they were mostly dismissed as PR-speak doled out to cherry-picked journalists. An outcome predicted —ironically — by Loksatta editor Kumar Ketkar, one of journalists invited to the press meet.

“Talking to the media is not important,” and more so because “if government has lost credibility so has the media lost credibility. [This would be> one non-credible agency talking to another non-credible agency,” said Ketkar on NDTV’s The Buck Stops Here the night before his tryst.

Ketkar’s remarks marked a rare moment of self-honesty that cut through much of media clamour surrounding Singh’s I-no-speak policy. In some news outlets, the demand that Singh redeem himself as a leader has been conflated with the demand that he be more media-friendly, using strategies borrowed from the West.

On the Barkha Dutt show, for example, his silence was recast as a bad PR strategy out of step with a new generation of Indians. “In age of hyper-communication, image is king and silence a shroud for a possible political grave,” opined the voiceover in the introductory segment flashing images of Barack Obama, David Cameron et al looking suitably cool. A claim reiterated by Dutt who accused political leaders, especially in the ruling party, of being stuck in the Stone Age.

“Culture of communication hasn’t evolved. The style is distant, remote and formal,” she complained. “Don’t citizens have a right to hear from their leader?” It is indeed imperative that a Prime Minister address the nation at regular intervals — more so in a moment of crisis — but must he also tweet, hang out on talk shows, hold town-hall meetings, and give countless media interviews?

The standard rebuttal to this demand will cite cultural differences, an argument offered up dutifully by Salman Khursheed, who said, “Our political culture doesn’t accept that kind of informality, and doesn’t accept that level of accessibility.” He’s not entirely wrong. Sure, Obama might get brownie points by coming on Jon Stewart’s show, but do we really want Manmohan-ji navigating the Rapidfire Round on Koffee with Karan? How about being watching our Prime Minister being hectored by our over-loud news anchors?

Besides, TV appearances in Western politics are media-savvy photo-ops, carefully choreographed to offer the illusion of intimacy and connection. They have little do with the more serious stuff of democracy, i.e. accountability and true communication. No one did them better than George Bush, who presided over a White House notorious for its high-handed secrecy.

Then there’s all this fuss over social media. New York Times reporter, Lydia Polgreen, said she’d love to see Rahul and Sonia Gandhi on Twitter “and that kind of give-and-take.” Even BJP General Secretary Ravi Shankar Prasad sang praises of Omar Abdullah’s tweets. If Angela Merkel has a Twitter account, why not hamara Manmohan. We’re all about talking directly to the people, right?

“This generation of voters seeks intimacy from its leaders. Old style of netagiri where you stood behind barricades with lakhs of people standing below just won’t work,” declared Dutt. Yet tweeting to tens of thousands of followers is hardly more intimate than a rally – one reason why it is favoured by Bollywood. Omar Abdullah’s tweets may be a hoot but they don’t make a whit of difference to his constituents, i.e. the Kashmiris. Most of them can’t access the Internet and certainly none are likely to think any better of him if they could.

Twitter does indeed promote “give-and-take”, but mostly with the chatterati in their social media bubble which includes, duh, reporters. Better yet, celebrity tweets make for eye-catching headlines. Journalists prefer their politicians hip, modern, and techno-savvy, but for reasons that have little to do with democracy.

All this fretting over the PM’s lack of visibility begs the real question: do we want Manmohan Singh to be a better Prime Minister, or just get better at PR? Politics in the United States is as much about image as substance. Hence, Obama’s 70-person media strategy team. If the camera doesn’t love a candidate, neither will the voters. But what makes for great press doesn’t always make for good governance – a fact that experts, citizens, and leaders bemoan alike come election season in America.

Singh’s problems of governance won’t be resolved by an image makeover aimed at “winning the hearts and minds” of his citizens. Unlike Americans, we don’t vote for a leader because, hey, we’d like to have a beer with the guy. We want a leader who clear sees our problems and has the strength, vision and —above all — a plan of action to resolve them. We want to feel like we’re in ‘safe hands’.

This is why we respond not to sound bytes and photo-ops but to issue-based leadership. We are the country of stodgy garibi hatao andholans, five-year plans, economic reforms, and Hazare-style anti-corruption movements. Indira Gandhi could connect with the masses, but she never pretended to be one of them. She made them believe that she could get things done. Mamata and Jayalalithaa epitomise the very same tough, can-do spirit today.

Yes, Manmohan Singh must speak, but to foster not so much a sense of connection – ‘I feel your pain’ – as a sense of security, i.e. ‘I can fix this’. We don’t need him to tweet, hold a town-hall meeting, or schmooze the media. Nor do we need to know about his pet dog or date-night with the wife. We want a Prime Minister who can tell us what we need to know when we most need to know it – and mean every word of it.

So, Mr. Prime Minister, do talk to the media but in open, transparent press conferences – just so everyone, including the journalists, are in the public eye. And an occasional televised speech won’t go amiss, especially when your cabinet ministers are in Tihar. Above all, just tell us this: what’s the goddamn plan? If you can sum it up in less than 140 characters, feel free to get yourself a Twitter account.

Audio extra: Firstpost’s Sanjeev Srivastava dissects the outcome of the PM’s meeting along with senior journalist T.R. Ramachandran:

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)