A simple constitutional amendment that has shifted back political power to the armed forces after decades of ‘guided democracy’ in Pakistan, promises of new constitutions/political systems in Bangladesh and Nepal, an oft-repeated ‘commitment’ (?) by successive governments to come up with a new statute in Sri Lanka and the opposition’s fears of the backward entry of autocracy after nearly two decades of faulty experimentation with multi-party democracy in the Maldives – and India suddenly gets the feeling of being surrounded by unsteady and/or autocratic regimes whose possible failures could affect the region as a whole in the coming years.

This leaves out extended neighbours in Myanmar in the East and Afghanistan in the West, with both regimes still battling for global recognition and acknowledgement without yielding an inch. Of the two, Myanmar went back to the control of the military junta after a short honeymoon with multi-party democracy, and Afghanistan is back in the hands of the religiously radicalised Taliban after twenty long years of sham democracy, imposed by the US from outside, with no hopes of successes at any point in time. As was known, the ‘democratically elected’ government, even in the best of times, did not go beyond the heavily barricaded and manned capital, Kabul, all of 275 sq km in a country whose total area remains 6.53 lakh sq km.

Similar Authority

The greatest significance of the emerging change is in Pakistan. Short of accepting military rule, the nation has adopted a new constitution that confers more power and authority on army chief Gen Asim Munir. He is now the constitutionally created Chief of Defence Staff (CDS), yes, but the real reactions from within the nation’s Navy and Air Force are not clearly known yet. Only the future will tell if the constitutional mandate is applicable to Munir, who got himself elevated as field marshal before the constitutional amendment. The alternative could be that his successor CDS too could enjoy similar authority, whether they come from the Army, Navy or the Air Force.

It is thus the institutionalisation of constitutional authority that Pakistanis and the rest of the world should be looking at, not just Munir’s term. Recalling how Maj Gen Ayub Khan became field marshal and how long and how far martial law went in the country – and took the country with it – is a lesson that needs to be remembered. Long before Munir, Ayub Khan was the one who opened strategic relations with the US, allowing Pakistani air bases to be used for spying on the erstwhile Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Quick Reads

View AllThe seed of the current developments in Pakistan lies in the people’s protest against elected Prime Minister Imran Khan a few years back. Those that spearheaded the protests and participated in them might not have thought about the possibilities, despite the nation’s long and arduous history involving military dominance in political affairs. That’s when the military was not in power. It is thus that the maxim, ‘Every country has an army, but in Pakistan, the army has a country’, came out of nowhere but has stuck – and stuck with Pakistan.

Ideology, Not Ideals

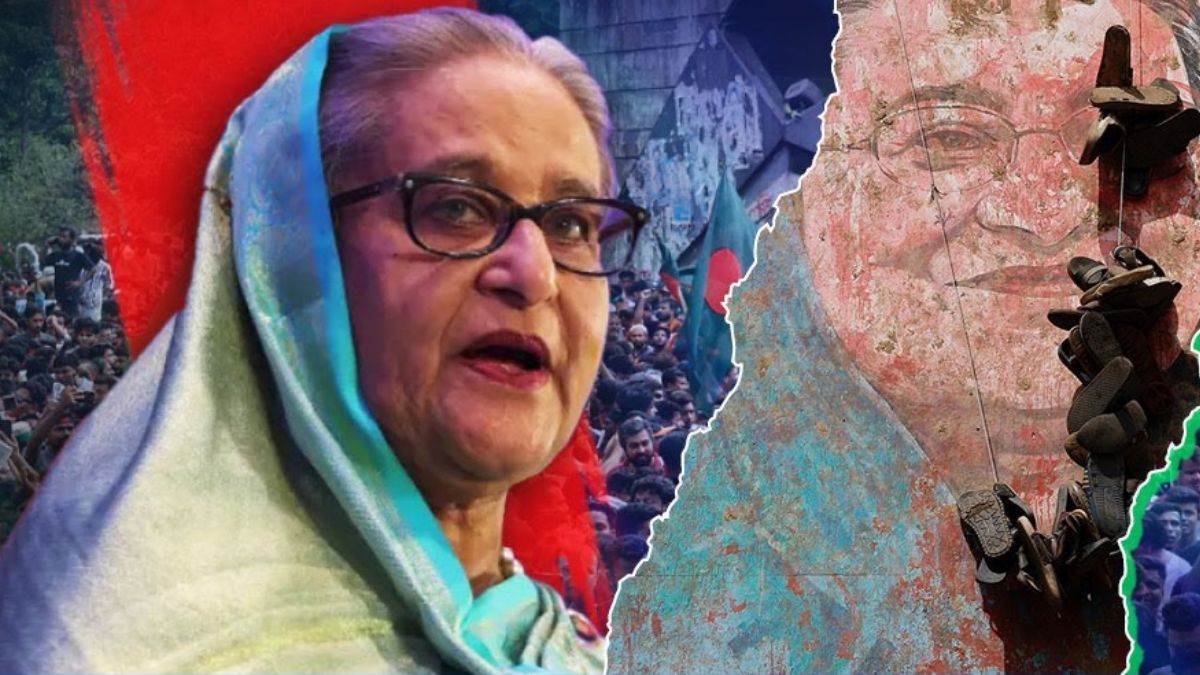

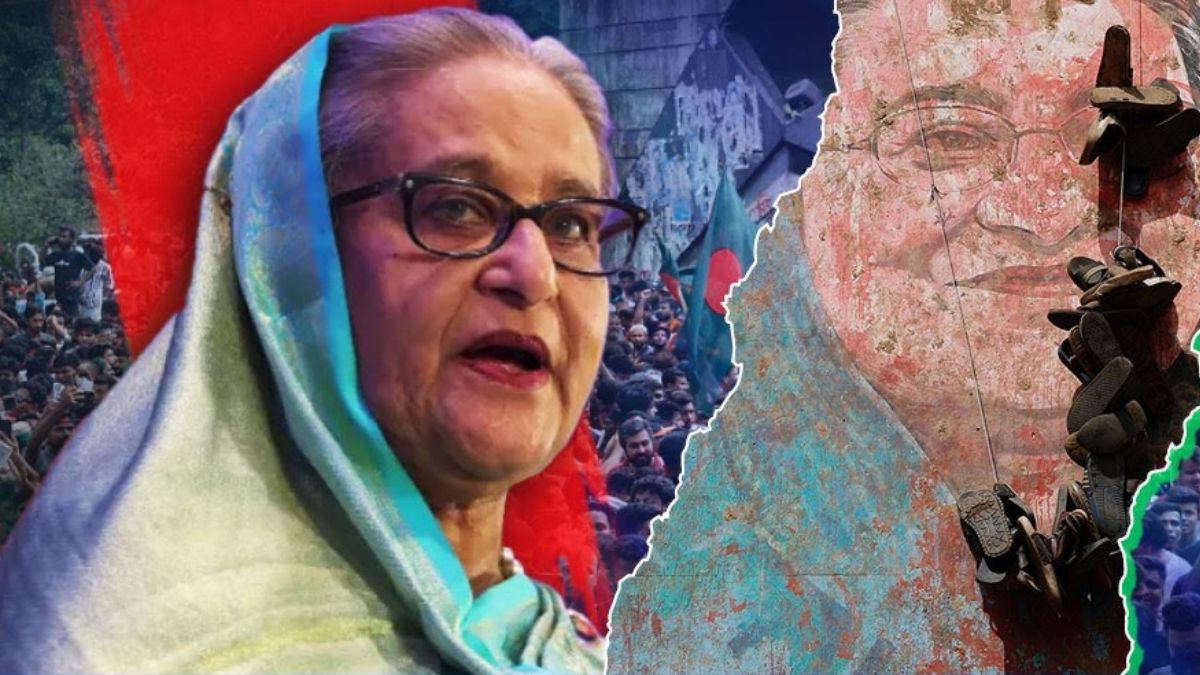

Then, we have Bangladesh, where the Gen-Z protests toppled the elected government of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. It is, however, anybody’s guess if the protestors, minus the student outfits and their leaders, actually knew or even cared to visualise what was in store. Yes, Bangladesh is nowhere close to becoming a military-controlled nation, but the growing influence of religiously oriented student groups may pose an even greater concern.

The aim seems to be to take Bangladesh back to the dark ages, or at least the ages when, as East Pakistan, it also suffered the consequence of military rule in the western wing. To be fair, post-Independence military administrators like Gen Ziaur Rahman and Gen H M Ershad were not known to be biased or cruel towards the local Bengali population, which manned the society and dominated the polity. Today, all sections of the policy, including the radicalised Jamat and the new student groups, too, are Bengali in character, but only in name.

Through a new constitution, they do not want to restore the ideals for which the nation was born in 1971 but to implant an ideology that is archaic and an assault on human dignity in many ways. The apprehension is if given to rule the nation for a full ‘elected term’, will the radicalised groups end up making Afghanistan out of Bangladesh? Indications are that they won’t be criticised or condemned for want of trying. The democratic alternative stares at the nation, but whether democracy will remain as free and active as in the intermediary past may be a question. That Sheikh Hasina contributed to the current situation through her ‘democratic autocracy’ cannot be overlooked as well.

Bringing to the Table

The other nation on which all eyes in the region have set their sights on is Nepal. Here after the Gen Z protests, ten communist parties have come together to form a new political party, with Puspa Kumar Dahal ‘Prachanda’, who was the darling of the Marxist militancy in the country once upon a time, as the coordinator. It means that post-unification, they could continue to fight over the leadership question, which was at the bottom of the continuing national crisis since the end of Marxist militancy. That a couple more communist parties have also not joined the new outfit, at least as yet, should show what Marxism and Leninism have come to in Nepal.

The question thus remains if the non-Marxist polity in the country, once centred on the Nepali Congress, could provide a viable electoral alternative. Like the Marxists, this section has also broken into multiple parts, in the name of ideology and principles – but actually owing to personal egos and political leadership issues. Or, is there going to be a third alternative, comprising and representing the student protestors? If so, what are they going to bring to the table in the name of form and reform – political, constitutional and administrative?

The question facing the tiny Himalayan Republic – the chances of the nation returning to royalty are remote – is as to what next in the name of restoring full-fledged democracy, when and how. No, it is not that democracy is the best form of government. But in the post-War, post-Cold War world, more and more nations and peoples have come to believe in it. This has made a visible and identifiable return to democracy the ideal way to keep the nation going. A military ruler or an autocrat otherwise cannot continue to enjoy political stability, nor hope to leave behind it as a legacy. Despite all the difficulties that the nation had/has lived with through the past years after the royalty, the Nepali armed forces have not been known to have usurped administrative power, nor known to have aspired for the same.

Aragalaya and After

That takes us to India’s southern neighbourhood, comprising Sri Lanka and Maldives, in the immediacy of IOR. The Aragalaya mass protests in Sri Lanka for regime change in 2022 did yield results, but only after the nation’s economy had been totally destroyed. What was pleasantly surprising for democracy-lovers inside the nation and outside, and equally shocking for the perpetrators of Aragalaya-linked violence, was the way the well-entrenched parliamentary democracy scheme ‘hijacked’ it all from those that had aspired to capture political power through a shortcut that was not overtly militant in form and content.

Once it became clear that parliament alone would elect a new president to complete the term of the ‘ousted’ Gotabaya Rajapaksa, as enshrined in the Constitution, the nation quietened. The fear of political instability vanished almost overnight. It gave the new president, six-time Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, and his team, time to focus all their energies on economic restoration. In context, the possibility of democratic elections just two years after the mass ‘struggle’ as Aragalaya in Sinhala means, is an apt lesson in establishing democratic credentials for the rest of them all, both in the South Asian neighbourhood and elsewhere.

Today’s unspoken problem in the island-nation could erupt through a new constitution that the present rulers under the once militant, JVP President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, and his NPP allies, had promised in their poll manifesto. Truth be told, every president since the mid-nineties – five, excluding the incumbent – has promised a new constitution, and some even went through the motions of drafting a new statute. It means the JVP’s promise of a new constitution is only old wine in an older bottle.

What they want to mix instead of the promised elixirs from the past is ‘systems change’, which they have left beyond what individual Sri Lankans have understood from the JVP’s militant, Marxist past. Whether they mean it the same way as they used to in a bygone era too is unclear. They are also not talking anymore about the abolition of the ‘Executive Presidency’, as promised earlier, and the kind of promise that every other president had made to the nation before getting elected – but not afterward.

There is also a lot of haziness in the JVP’s interpretation of ‘power-sharing’ with the minority ethnic Tamils. But they seem keen on upstaging the politically stymied 13th Amendment, mooted by India as far back as 1987, which created Provincial Councils, now all defunct, after successive governments delayed and denied periodic elections, citing new legal hassles that they themselves had created for the purpose. That is to say, when the mass protests did not destabilise the democratic process, a new constitution, if the ruling JVP is serious about it, has the potential to achieve precisely the same.

Maldivian DNA

Bhutan and Maldives are the youngest democracies in the region. Both became one in 2008. Democracy is said to have taken deeper roots in Bhutan, which is still governed by the royals, but mainly owing to the initiatives of the rulers, who readily surrendered their inherent powers and powers to people’s representatives through a constitutional arrangement. In a way, barring India, Bhutan is the only South Asian power where democracy, as visualised generally, has taken root. That is when you leave out the Sri Lanka story.

The same cannot be said of the Maldives, where parliamentary democracy is in full steam, but on paper, some would say. The archipelago nation has had the history of being the longest ‘parliamentary autocracy’, under President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, for 30 long years, from 2008. Today, nearly after 20 years and four presidents, the tentativeness of the nation’s democratic path should be worrisome for those that had high hopes on this score. The irony is that the internal squabbles within the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP), which was the backbone of the nation’s democratic endeavours from the start, are to blame for much of the continuing chaos.

Maybe it is in the Maldivian DNA, but the spirit of one-man royal rule dates back prior to the nation becoming Islamic in the twelfth century – when it still had Hindu and Buddhist kings – but even today, elected leaders act as if they are ‘elected sultans’, whose administration and politics should not be questioned, nay, challenged. With the result, today we have the youngest of ‘em, Mohamed Muizzu, literally an ‘accidental president’ since the 2023 elections, acting as if he were the lord of all he surveys.

Muizzu has gone one up on even Gayoom and the latter’s half-brother Abdulla Yameen, who in turn was the incumbent’s mentor, when it comes to de-democratising democracy in the Islamic nation. He is sitting pretty on a conservative vote bank (not all of them radicalised) passed on by Gayoom through Yameen and has been targeting every democratic institution, including Parliament and the Supreme Court. He provided a sample when he had inconvenient Supreme Court Justices out of work on corruption charges just an hour before they were to hear an anti-defection law that he had heavily one-sided Parliament pass hastily.

The domestic debate is if Muizzu will go the whole hog in becoming an autocrat – and if so, how much more – before his re-election bid in 2028. The irony is that in the place of multiple political parties, most of them active with a certain voter base, at democratisation, the nation’s Opposition has been reduced to a demoralised MDP, whose leaders are still un-united, and Yameen’s People’s National Front (PNF), created out of nowhere after President Muizzu had hijacked the two parties he had headed – the Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM) and the People’s National Congress (PNC). To cut the long story short, Maldives today is at the democratic crossroads, and the years until the next presidential poll (2028) are crucial in deciding which way the nation will go.

Docile Democrats

Barring Bhutan, thus, India’s neighbourhood is going through politically unstable times. It is not just about the domestic consequences that New Delhi would have to be concerned about. In the contemporary context, the fact that among the immediate neighbours, Pakistan, Bangladesh and the Maldives are Islamic comes with its own burden in terms of internal security for the Indian nation and people.

Any further eruption of unsettling situations in any or all these nations can push new refugees across India’s borders. Democratic elements in these countries, like most elsewhere, are also docile and discreet. They would not want to encounter mobs, as witnessed in Bangladesh and Nepal. In Sri Lanka, in comparison, the Aragalaya protests were relatively civilised.

Even there, no answers have been found about the why and how of the coordinated arson that targeted the property of the ruling elite of the time, starting with President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and his successor, Ranil Wickremesinghe. The sudden end to the arson, just as it came, and the fact that no one was frightened out of his wits under the circumstances, too, augured well for the nation’s people and entrenched democracy. But it cannot stay that way all the time. Thankfully, no one is predicting another Aragalaya-kind of mass uprising any time soon, despite the perceived failure of the incumbent centre-left leadership to arrest prices and inflation, as expected and promised.

Guarded all the Time

Whether it is the importation, re-routing or out-sourcing of Kashmir-centric cross-border terrorism, or the mere arrival of a mass of refugees, including Rohingyas from Myanmar, where there is unending unrest and civil war-like situations even otherwise, India needs to be guarded all the time. Early indications that the perpetrators of the recent Delhi car-bomb blast were trained by a Turk should be a cause for concern – whether it was accidental that he came from Turkey or is reflective of the recent strategic forays that Turkey has been making in India’s neighbourhood, in Pakistan, Nepal and the Maldives? Or is it that Pakistan has outsourced its job to Turkey, a distant player, after Surgical Strikes and Operation Sindoor?

Of course, the Indian agencies would have their answers any time soon, but that knowledge could give only limited solace. It’s so because the unsettling socio-political conditions in India’s neighbourhood trigger enticing possibilities for all those wanting to create problems for the nation – whatever the reason and whoever the motivator and enforcer. After all, behind Sri Lanka’s Aragalaya, the names of very many nations were mentioned, though the sudden death of the protests once President Gota quit overnight ended the speculation and consequent debate – but without answers.

(N Sathiya Moorthy, veteran journalist and author, is a Chennai-based policy analyst and political commentator. The views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)