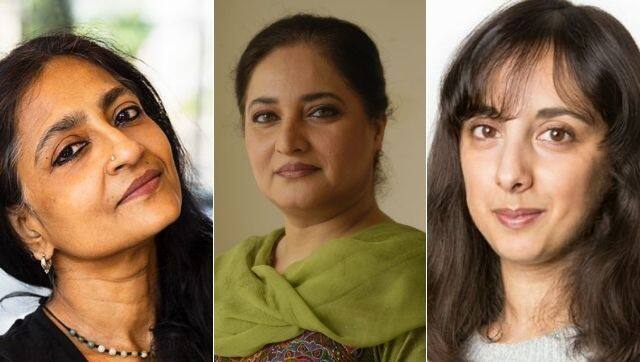

The following article includes mentions of sexual abuse. Reader discretion is advised. *** In 2017, the Madras Music Academy, a leading training institute in the performing arts, did something unprecedented — it set up an internal complaints committee for sexual harassment, after one of its secretaries featured in Raya Sarkar’s contested List of Sexual Harassers in Academia (LoSHA). However, it was not until 2018 when the second wave of #MeToo swept through the expansive world of the Indian arts, alongside cinema and media, that questions began to be raised explicitly on its abusive hierarchical structures and culture of silence. How does one challenge a centuries-old system of learning founded on skewed power dynamics that allows unquestioned access to a disciple’s body and being? How does one then, institute and formalise the questioning of said access and its systemic abuse? As skeletons began tumbling out of the closets of several hallowed halls of learning, social media was rife with allegations of sexual harassment against powerful men who, until then, held the reins of some major cultural and creative empires in the country. From fine arts to classical music, the rot was deep. And while the knowledge of such widespread sexual misconduct in the fields was acknowledged as an “open secret”, its institutional redressal became a disputed terrain as establishments found themselves largely ill-equipped to deal with the fallout of the watershed moment. Earlier last month, as I tuned into a webinar titled ‘Abuse of Power: Sexual Harassment In the Arts’ hosted by the India Habitat Centre, I wondered if three years down the line, cultural organisations in India are any better endowed to socially and legally cope with incidents of sexual abuse. Supreme Court Lawyer Mihira Sood, who specialises in women’s rights, had Dr Ananya Chatterjea – Professor of dance at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and an exponent of Odissi — for company, with Dr Arshiya Sethi, dance scholar and media personality, moderating the conversation on Zoom. It was the first in a five-part webinar series titled ‘Arts and the Law: What they don’t teach in art class’. Right at the outset, Sood laid the foundation for the dialogue by establishing how an asymmetrical distribution of power between the student and the teacher in the Indian arts — especially in the classical performing arts — makes this traditional sphere especially vulnerable to incidents of sexual abuse. “I do believe that anyone who is serious about the preservation of the arts will appreciate the need for reform precisely for that reason, however uncomfortable or difficult it may be in the beginning, and however difficult it may be particularly to go against icons and stalwarts of these arts one has always looked up to. It’s not easy,” she said, before adding that in the event of an incident of sexual harassment at an institution, “whether or not one is open to the idea of reform in the arts, the legal obligation to address these issues already exists through a range of legislation.” The presence of the Sexual Harassment Act, along with the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act and the Indian Penal Code, provide an umbrella of existing legislation, which, according to Sood, “in a way fills in the gaps that another legislation may have left out.” The principle premise of the Indian arts is that of devotion, which, more often than not, translates into worshipping custodians of the form through the guru-shishya parampara (teacher-student tradition) perpetuated via the institution of the gurukul. It is an immersive form of residential learning, as Mihira elaborates, conventionally lending itself to assuming the features of a religious cult. The figure of the guru, thereby, attains a divine and invincible halo, which in turn significantly skews the power scales in favour of the teacher, who is granted unbridled and unchallenged access to their disciples’ bodies. “The Sexual Harassment Act, however, is limited to women,” Sood noted. “Its intent was to provide a civil remedy to people who do not wish to necessarily take a more aggressive route of criminal complaint, which entails going to the police station, and having the perpetrator perhaps face a prison sentence. This Act, however, does not preclude the filing of a criminal complaint. And in cases where the Sexual Harassment Act may technically not be applicable, the option of a criminal complaint under the Indian Penal Code already exists,” she said. She also underlined that individuals who can be aggrieved under the Sexual Harassment Act include “people in the position of apprentices. It includes people who are working in any kind of institution, including a domestic dwelling house, whether or not for paid wages. And that will then cover a lot of people who are in the tutelage of gurus in performing arts as well.” [caption id=“attachment_8919241” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  From left: Ananya Chatterjea (image courtesy: ananyadancetheatre.org); Arshiya Sethi (image courtesy: Arshiya Sethi); Mihira Sood (Twitter/mihira_sood)[/caption] The POCSO Act, in the context of Indian arts, therefore acquires heightened relevance considering the young age at which individuals usually begin training in an artistic discipline in India. The Act does not permit any clemency, owing to the absence of informed and active consent in case of survivors who are minors. The consequences of not addressing such grievances institutionally are both legal and social, the latter having manifested into the #MeToo movement, social media call out and cancel cultures, and de-platforming of perpetrators, as has been witnessed in the past. Celebrated artist Riyas Komu stepped down from a platform of his own making, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, after allegations of sexual harassment were brought against him in 2018. (Komu refuted the accusations, whilst apologising if he had inadvertently caused hurt.) Sotheby’s India’s former managing director Gaurav Bhatia resigned post a month-long leave of absence after four allegations ranging from inappropriate touching to physical assault were levelled against him. There has also been pushback: The artist Subodh Gupta sued the Instagram account @herdsceneand in the Delhi High Court for defamation, for airing anonymous allegations of misconduct against him. The parties later reached a settlement in court. The insular world of Indian classical performing arts was stirred by the Madras Music Academy debarring seven Carnatic musicians, named in various #MeToo accounts, from performing at its Margazhi music festival in 2018. More recently, the founders of Bhopal’s residential music institute Dhrupad Sansthan — the late Pt Ramakant Gundecha, pakhawaj player Akhilesh Gundecha, and chairman Pt Umakant Gundecha — have also been accused of sexual harassment by current and former students. “While one may have legitimate criticism of these movements, it’s important to acknowledge that they have arisen, in a very large part, as a result of non compliance with both the letter and the spirit of the law,” Sood observed, during the webinar. “And that is an important point to make, that even where the letter of the law allows for some leeway, there is really very little excuse for not complying with what is the spirit of the law, which is to prevent the abuse of power in a manner that is sexual in nature. And that’s a specific problem because it has enormous implications, not just in terms of the physical violation, or the loss of dignity that a person may suffer, but also the loss of talent to an entire industry when people are afraid to become a part of it; when they see there is no redress.” One may therefore surmise that as powerful as the reach of social media is, the reactions it births are largely knee-jerk, paving way for — but not necessarily ensuring — fundamental reform. This brings us also to the concept of the gurudakshina, a significant spin-off of the gurukul, which entails repayment offered to a teacher for their guidance in the discipline, after having surrendered oneself to their mercy. The deep-seated flaw of this construct nurtures personality cults, which in turn commodifies individuals at a lower rung in the hierarchy, stripping them of agency. Consequently, the spotlight shifts from the art to the artist, encouraging a practice that corrodes the form at its core. In the performing arts like dance, physical contact between individuals might often become unavoidable, especially when the teacher is required to “correct” the postures of a student. How, then, can this be achieved consensually? Moreover, what of instances when the student is in love with the teacher, and is willing to forswear themselves in ways that are bound to generate conflict among fellow students and members of the ecosystem? In response, Sood emphasised on the importance of steering clear of such relationships in professional spaces, “because there isn’t really any way that it can be fair to the other students, or the person really has a way of saying no, or exercising agency in any way.” She added that it is “really up to the guru in that case to draw those lines, and to be a lot more professional and sensitive about it. And when it comes to younger students, minors in particular, then the question of consent does not even arise, and it is straight away a criminal offence that invites very serious punishment.” Do these ‘provisos’, then, threaten to dismantle the already endangered guru-shishya parampara and the gurukul tradition? (At this point, one must also remember that informal learning is not exclusive to the Indian arts, and is often practiced in other countries and disciplines like sports and academia as well.) Mihira dismissed the concern, stating how the idea of reformation in the Indian classical arts should not instigate the formulation of a false dichotomy of tradition versus modernity. That was never the debate to begin with. While nouveau art forms have lent themselves to greater public criticism and scrutiny, the traditional arts have largely remained insular to it, allowing very little dialogue and change to trickle in. “I think anybody would agree that the essence of this guru-shishya relationship is one of respect, and that it need not be one of worship. And while there is a certain beauty in the idea of complete surrender and devotion, I think it’s important to remember that that devotion is to the art, and not to the artiste, or to the teacher,” she said. Ananya Chatterjea weighed in on this distorted dynamic of power in the traditional arts, talking about how this grave disparity plagues the world of contemporary dance as well. “There are choreographers who are called out because they have favoured sexual relationships with artistes they are working with, and casting depended on that. And the dancers are in (such) a position, while they are on tour, that it is difficult for them to speak up,” she said. Performers, while on tour, have often had to compromise on their privacy, safety and comfort upon being asked to share rooms with an individual above them in the hierarchy, due to budgetary constraints. “It is important to understand that even when there is consent, these are hierarchical relationships, so they will always land as acts of power,” said Chatterjea. She reads the discrepancies in this system as repercussions of its foundation built on the “unquestioned access” granted to the guru, which is “exemplified in the story of Dronacharya asking for Ekalavya’s thumb” as gurudakshina: “I bring this up because our Dalit activists have so clearly pointed out that without an intersectional analysis of caste being at the core of this (phenomenon), and any kind of power analysis, we are actually missing the kinds of violences — the levels of violences — that are implicit in the system.” The question, then, is what constitutes a safe space for the arts, and how does one restore balance and equity in a heavily unequal relationship, thereby further redirecting the conversation to the central argument of who ultimately has access to my body, besides me. This triggers traumas stowed away in dark, unremarkable corners of my mind, from the time I was nine-years-old: On the pretext of helping me with “corrections”, my art teacher’s hands had roved under my frock for weeks and months, while my parents went about their routines in the adjacent rooms of our home. I was at an age when I did not even know the words for what was happening to me in the three languages I was fluent in. It was only much later that I finally mustered the courage to tell my mother that I did not want to continue with the lessons, even though I was over a decade away from putting into words the magnitude of the violence I had been subjected to.

My body and mind, in response to the inexplicable suffering, had revolted — by expunging my ability to draw human figures, or anything that resembled the man who had taught me how to draw them to perfection. Today, I can barely manage to scribble stick figures, trees and huts.

This makes me wonder if children are now any better equipped to deal with traumas born of sexual abuse, emotionally and mentally. It is also at this juncture that I ask myself when and how my body had learned to discern the difference between the goodness and the badness of the same touch, on the same spot, by the same person on different days.

As if on cue, Chatterjea responded to my train of thought with her next comments: “What I have come to understand is that while touch maybe okay on one day, it may not be okay on another”.

“I feel like what you have called for is ‘pedagogical innovation’. How can we offer feedback without touch; how can we offer feedback about alignment; how can we set up an atmosphere in the classroom, so that the students can place the cards and can actually say ’no’. Because it is one thing to say, yes, there are possibilities I could have said no. But did I feel comfortable, given that everyone else was saying ‘yes’? Did I want to stand out?”

The dilemma is real, and crippling. Chatterjea further illustrated lucid instances of how an environment of hostility and distress is perpetuated through unspoken and unthought gestures, especially for subordinates in the ecosystem. “What we have learned a lot from theatre here, is that there are what you call ‘intimacy choreographers’. So, you know, if I go towards the students [with hands held out] and say, ‘Can I touch you to offer this feedback?’ — my hands are already out. There is already a power system that has been set up by the teacher-student relationship, and then me coming towards them with my hands out — it’s awkward for them to say no,” Ananya explained. The objective, then, is to create a culture of consent as teachers, without objectifying the bodies of the performers. The aim is to also demolish the voyeuristic gaze that systemically incriminates the survivor more than the perpetrator, through a stifling culture of silence. However, it is crucial to remember that such violence is certainly not exclusive to the artistic gurukul, but is also prevalent in domains where bodies of individuals lying on the lower layers of the pyramid are easily accessible. “I would also like to mention it’s not just the guru, but because of the uncertainties involved with the arts — similar kind of uncertainties are involved in sports as well — they are such that even sponsors, promoters, organisers of your programmes, anybody who can project themselves in this unequal power relationship, has exactly the same position. Maybe they’re lacking the divinity aspect that the guru has, but it is much larger than the guru-shishya parampara. Unfortunately, it has been restricted to the guru in the imaginations, but the issue is far larger than that,” said Arshiya Sethi. The perversion of the craft beyond the guru-shishya tradition in societies — like the West — where students are encouraged to question and debate with their mentors can be attributed to the “culture of scarcity”, or paucity of jobs in the field, observed Ananya Chatterjea. In order to safeguard one’s means of livelihood, people are often compelled to not disturb the status quo. In this event, the onus falls largely on governments and institutes to regulate patronage granted to accused individuals, thereby increasing accountability. (It made me wonder if my perpetrator had received any monetary help from the State, thereby laying claim on taxpayers’ money…my money.) “While it may be a personal choice for an accuser, or for somebody to consume or not consume somebody’s art or performance, I think there’s certainly a far higher obligation on institutions and government bodies when it comes to looking at who they’re going to be supporting monetarily, and in terms of awards,” said Mihira Sood. This led Ananya Chatterjea to round off the conversation with her thoughts on how perceptions of accounts can often perpetuate “lateral violence” — an act that entails an investigation of the manners in which we listen to and dismiss other’s stories. This implosive and contagious channel of toxic communication leaves individuals at the same level of powerlessness further disenfranchised, on account of hostility directed towards one’s peers, resulting in a person feeling irrelevant and invisible. As the discussion concluded, I was left pondering the far-reaching implications of unspoken intent, seemingly innocuous gestures, and a machinery of trust that precludes — even incriminates — consent. It demands the autonomy of one’s mind, body and resources, failing to grant which invites expulsion from an exclusive club — founded on the exploits of caste, class and gender.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)