“The atrocities perpetuated at Amritsar have proved that Imperialism run mad is more dangerous, more vindictive, more inhuman, than a frenzied uncontrollable mob.”

Kishwar Desai begins her book with words by Lala Lajpat Rai, which were written as a foreword to Pandit Pearay Mohan’s An Imaginary Rebellion and How it Was Suppressed.

In Desai’s Jallianwala Bagh, 1919: The Real Story, one finds accounts of the horrific misdeeds of a colonial regime that are often spoken of along with the reports that are on record, but which are inevitably distanced from the mainstream narrative. These are the tales of ordinary people fighting an oppressive regime, of atrocities against civilians, the widespread prevalence of racism and a pre-planned effort to divide and rule a diverse community.

Official figures indicated that the firing at Jallianwala Bagh on 13 April, 1919 exhausted 1,650 rounds of ammunition and killed 379 people, wounding 1200. The Indian National Congress reported more than a thousand people dead and nearly 1,500 were injured.

In her book, Desai writes about a multitude of incidents that led to this massacre nearly a hundred years ago and the aftereffects of the attack on the residents of Amritsar. “It all started with a photograph,” she says.

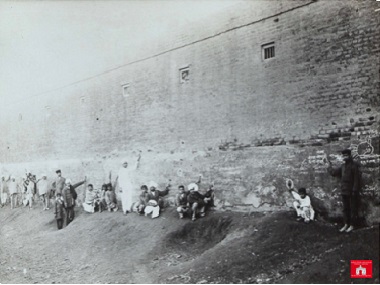

Desai, who is the chair of the Arts and Culture Heritage Trust that set up the Partition Museum in Amritsar, was gathering material on the history of the Town Hall (situated next to the Bagh) with her team. One day, she came across a photograph of the Town Hall burnt down during riots. It was dated 1919.

Extensive research led her to more photographs around the same timeline as the incident on that Baisakhi day, and she was able to draw a picture of how the people of Amritsar were trapped by the British, not only at Jallianwala Bagh, but in the whole city. Accounts of the humiliation they underwent also surfaced in her readings.

The history of Amritsar is one of great significance to the author. Her grandmother was a little girl during the attacks. Not many families spoke up back then about the atrocities inflicted on the people. One of the reasons, Desai concurs, was perhaps that any anti-British protest such as those against the Rowlatt Act would have led to immediate arrests and torture.

Desai elaborates in her work using reports of the Hunter Committee, those of the Indian National Congress and other archives — the testimonies that changed the way she looked at Jallianwala Bagh.

She put together material from those few accounts of the people who were actually present at the Bagh on 13 April. And slowly she came to realise that the story was not just about Amritsar; it was about the undivided Punjab that witnessed scores of riots when the British tried to suppress the protests against Mahatma Gandhi’s arrest. And after reading about the two officials infamously associated with Amritsar — Colonel Reginald Dyer and Sir Michael O’Dwyer — Desai says, “I formed very different opinions about both of them.”

The historical narrative that has been handed down has always suggested that Dyer was responsible for what transpired, but while researching, Desai realised that it was a series of wrong decisions by O’Dwyer – the arrests of Saifuddin Kitchlew and Satya Pal, the oppression inflicted through the Crawling Order, punishments following an attack on an Englishwoman – that instigated a reaction from the people of Amritsar prior to the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh. “Dyer was in fact just one of the many officers following orders in Amritsar. None of them were operating on their own.”

The British pinned the blame on Dyer, she says, and made him look like an aberration for fear that people would never look upon them as being fair and just again.

Holding Dyer accountable for the massacre and the atrocities in Punjab shifted the blame from the system as a whole to one bad individual.

The repercussions of these incidents were felt all over Punjab but for the British, the author states, it was all pre-planned.

If Jallianwala Bagh was the end of any coexistence of the colonised with the imperial power, it was the incidents that occurred in the days before the massacre that dealt the final blow.

The British recruited a bulk of their army from Punjab to fight during World War I and the people of Punjab believed in mutual trust between Indians and the colonial regime. Before Jallianwala Bagh, the Indians and the British were working together. Atrocities inflicted were sporadic and the freedom movement was in its nascent stages. Indians travelled abroad and returned inspired by ideas of liberty and home rule.

But Jallianwala Bagh was the first time that atrocities were inflicted on defenseless people, and Indians saw a very different side to the British. Slowly, the society realised that this was a deeply racist colonial power. “Punishments were all meant for Indians,” Desai explains and it was when Amritsar was put under pressure that the idea of freedom completely solidified. “One by one all the leaders started distancing themselves from the British,” she added.

The massacre caused social and economic mayhem, however, the immediate impact was that the Hindu-Muslim unity that was being forged was impacted greatly, Desai opines. The immediate impact was that the British took away members from each community and made them confess against each other. Brutalities rose to the extent that individuals were shot dead in front of their relatives for no reason. “There was no media, no one to turn to,” Desai says. The situation became a question of survival.

Those wounded were arrested by the British and when doctors who treated them spoke to the survey officials, they were left wondering if their statements would have led to further problems. “Some of these things happened inadvertently, but the British were very clear that they were not going to give any treatment to Indians.” Many, Desai writes in her book, succumbed to their injuries months after the incident for want of medical aid.

Economically, Amritsar suffered. Many traders, doctors, lawyers were not able to work for months – they were sick, or in jail or simply prohibited under curfew. Coupled with the Partition and the world people woke up to after Jallianwala Bagh, according to Desai, one wonders whether Amritsar ever recovered, because the constant pressure put on the city by the colonial regime never stopped.

Yet, it was the ordinary people who were really carrying forward the battle in each of these places; people that we don’t even know of, Desai says mainly, because they are considered minor actors in a larger historical context. But it was the smaller characters, these nameless individuals in all the cities, that made possible a massive freedom movement.

Desai says that she still has a lot of questions about how Amritsar fared in the years to come. She is currently working on a subsequent addition to the book that details what happened after the attack and the martial law that followed.

Kishwar Desai’s Jallianwala Bagh, 1919: The Real Story is published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications

)

)

)

)

)