Editor’s note: Kolkata and the Sundarbans face a deadly melange of climate change impacts: Intensifying heat waves and rainfall extremes, an exceptionally rapid rise in sea levels and intensifying cyclones. Chirag Dhara, a climate physicist, visited Kolkata and the Sundarbans in November 2018. He interviewed a wide cross-section of people – college students and professionals, taxi drivers and street dwellers – on their experience of changes in their city’s climate. He also spoke to experts and activists working in health, science and environment. This five-part series integrates public perception with expert opinion. It contextualises local climate trends within country-wide and global trends, using photographs, videos, satellite imagery, infographics, concept schematics and the latest developments in climate research. Important scientific concepts have been simplified to better explain the causes and consequences of these changes. This is the first part of the series. Read all the stories in the series here

A deserted street in Kolkata during a heat wave. Image: Sagarika Bose[/caption] These were sentiments echoed by the entire spectrum of people I spoke to in Kolkata. Students and professionals, cycle-rickshaw and taxi drivers, street dwellers and businessmen — all agreed that the city sees longer summers, more intense heat waves and diminished winters. Rising temperatures are a fact of life in Kolkata and are, it would appear, in line with global climate change. Despite the strong convergence in public opinion, caution is warranted in interpreting the changes that the city is seeing. As Bertrand Russell once eloquently quipped, “The fact that an opinion has been widely held is no evidence whatever that it is not utterly absurd!” That makes it imperative for us to ask some fundamental questions: - Do the records in Kolkata bear out public perception? - Why are these changes happening? - Does it matter? - What does the future hold? Has Kolkata warmed and by how much? (Temperature rise in the region around Kolkata from 1850 to 2017 using the average of 1951 – 1980 as baseline. Data:

The Carbon Brief

) Temperature records for Kolkata show that there have been substantial fluctuations in temperature from one year to the next. For instance, not only was 1971 a much colder year on average than 1970 and 1972, it was also colder than 1900! Yet, for all these short-term fluctuations, a clear-long term trend emerges. There has been a robust long-term rise in temperature around the city by about 1.2 degrees Celsius in the past 170 years (methodology for the calculation is

explained here

). Q&A: How do we know temperatures from as far back as the 1850s? In the more densely populated parts of the world, temperature records exist since the 1850s. Older records are unsurprisingly sparser, more patchy and error-prone than data from satellites and modern equipment available for recent decades. Yet, error-estimation techniques, consistency checks with

alternative methods

and historical climate modelling have made even older data useful to formulate a long-term historical perspective on temperature rise. Kolkata is warming more rapidly than the global average as well as most other megacities in South Asia. Kolkata’s temperature rise is, of course, happening within the broader canvas of anthropogenic global warming that is afflicting the entire planet. The earth’s average temperature has risen by about

1 degree Celsius

since pre-industrial times. What this fact conceals is that different parts of the world have warmed at significantly different rates. This non-uniformity, for which there are

several reasons

, is beautifully visualized in

this NASA simulation:

A deserted street in Kolkata during a heat wave. Image: Sagarika Bose[/caption] These were sentiments echoed by the entire spectrum of people I spoke to in Kolkata. Students and professionals, cycle-rickshaw and taxi drivers, street dwellers and businessmen — all agreed that the city sees longer summers, more intense heat waves and diminished winters. Rising temperatures are a fact of life in Kolkata and are, it would appear, in line with global climate change. Despite the strong convergence in public opinion, caution is warranted in interpreting the changes that the city is seeing. As Bertrand Russell once eloquently quipped, “The fact that an opinion has been widely held is no evidence whatever that it is not utterly absurd!” That makes it imperative for us to ask some fundamental questions: - Do the records in Kolkata bear out public perception? - Why are these changes happening? - Does it matter? - What does the future hold? Has Kolkata warmed and by how much? (Temperature rise in the region around Kolkata from 1850 to 2017 using the average of 1951 – 1980 as baseline. Data:

The Carbon Brief

) Temperature records for Kolkata show that there have been substantial fluctuations in temperature from one year to the next. For instance, not only was 1971 a much colder year on average than 1970 and 1972, it was also colder than 1900! Yet, for all these short-term fluctuations, a clear-long term trend emerges. There has been a robust long-term rise in temperature around the city by about 1.2 degrees Celsius in the past 170 years (methodology for the calculation is

explained here

). Q&A: How do we know temperatures from as far back as the 1850s? In the more densely populated parts of the world, temperature records exist since the 1850s. Older records are unsurprisingly sparser, more patchy and error-prone than data from satellites and modern equipment available for recent decades. Yet, error-estimation techniques, consistency checks with

alternative methods

and historical climate modelling have made even older data useful to formulate a long-term historical perspective on temperature rise. Kolkata is warming more rapidly than the global average as well as most other megacities in South Asia. Kolkata’s temperature rise is, of course, happening within the broader canvas of anthropogenic global warming that is afflicting the entire planet. The earth’s average temperature has risen by about

1 degree Celsius

since pre-industrial times. What this fact conceals is that different parts of the world have warmed at significantly different rates. This non-uniformity, for which there are

several reasons

, is beautifully visualized in

this NASA simulation:

The average temperature rise in India is roughly the same as the global average. As before, this conceals the fact that some parts of the country have warmed much more than others. In what amounts to an unhappy validation of Kolkata’s public opinion, it is this city that has seen the highest rise in temperature among the largest megacities of the Indian subcontinent.

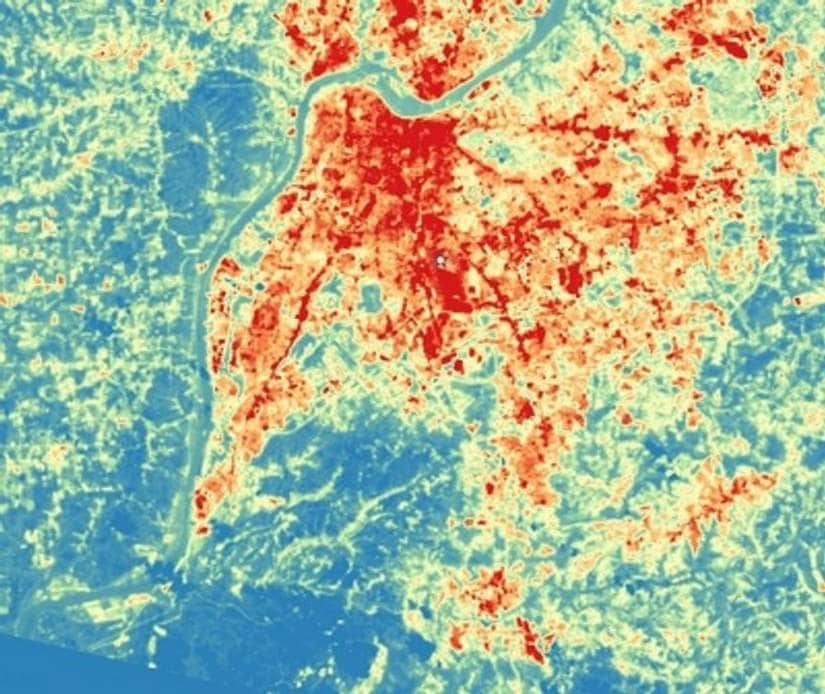

Higher temperatures in the city of Louisville

in the US relative to the countryside measured by satellite: the Urban Heat Island Effect. Credit: Climate Central.[/caption] This effect can be powerful enough at the scale of a city, or sections of it, to swamp temperature rise because of greenhouse gases. However, this effect being localised to city scales only affects the microclimate of the city and has little effect on the global average temperature (most of the Earth’s surface is covered by water or is sparsely populated). Why is a mere 1.2C rise in temperature a cause for concern for Kolkata? “Summers are especially difficult for people like us who work on the streets. Heat strokes are very common”, a street worker told me. He cycles around the city all day with bags full of cigarettes delivering them to the local stores. Extremes, though rare, pose the gravest risks to our lives and livelihoods, as evidenced by the

thousands that died

during the record 2015 heat waves in India and Pakistan. Prolonged heat waves can also devastate crops

as happened in Europe

in summer 2018, sending food prices rocketing, and disrupt power plants because of a spike in load. [caption id=“attachment_6107561” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Higher temperatures in the city of Louisville

in the US relative to the countryside measured by satellite: the Urban Heat Island Effect. Credit: Climate Central.[/caption] This effect can be powerful enough at the scale of a city, or sections of it, to swamp temperature rise because of greenhouse gases. However, this effect being localised to city scales only affects the microclimate of the city and has little effect on the global average temperature (most of the Earth’s surface is covered by water or is sparsely populated). Why is a mere 1.2C rise in temperature a cause for concern for Kolkata? “Summers are especially difficult for people like us who work on the streets. Heat strokes are very common”, a street worker told me. He cycles around the city all day with bags full of cigarettes delivering them to the local stores. Extremes, though rare, pose the gravest risks to our lives and livelihoods, as evidenced by the

thousands that died

during the record 2015 heat waves in India and Pakistan. Prolonged heat waves can also devastate crops

as happened in Europe

in summer 2018, sending food prices rocketing, and disrupt power plants because of a spike in load. [caption id=“attachment_6107561” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Melting asphalt during a heat wave in Delhi on 27 May, 2017. Image: Harish

Melting asphalt during a heat wave in Delhi on 27 May, 2017. Image: Harish

Tyagi/EPA[/caption] In much the same way as smoking elevates the risk of lung cancer, rising average temperatures have an outsized effect in amplifying the intensity and duration of heat waves.

Research published in 2015

found that “very intense heat waves” occur three times as often in a world warmer by 1.2 degrees Celsius and “extremely intense heat waves” occur about ten times as often as they would in the cooler pre-industrialized world. To be clear, the likelihood of heat waves does not depend on local temperatures alone. Yet, the world is already warmer on average by 1 degree Celsius and is on track for a rise of

at least 3.2 degrees Celsius

in the next 70-80 years, at which point “extremely intense heat waves” would occur a horrifying 50 – 100 times as often. The exacerbating effect of humidity What makes heat waves in Kolkata far more dangerous than just the rise in temperature would suggest is the city’s high humidity, averaging 75 percent in May and higher during the monsoon. The dry heat of Delhi or Hyderabad is not as physiologically taxing as the humid heat of Kolkata, Chennai or Mumbai. The 2015 India/Pakistan heat waves turned out as deadly as they did because there was a simultaneous spike in both temperature and humidity, events that

were magnified by global warming.

It is the conspiring combination of high temperature and humidity in the entire Gangetic plain, in which Kolkata lies, that makes this region one of the most heat stressed parts of the country. It has made summer conditions in Kolkata

already push very dangerous levels of heat stress today

. [caption id=“attachment_6107571” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

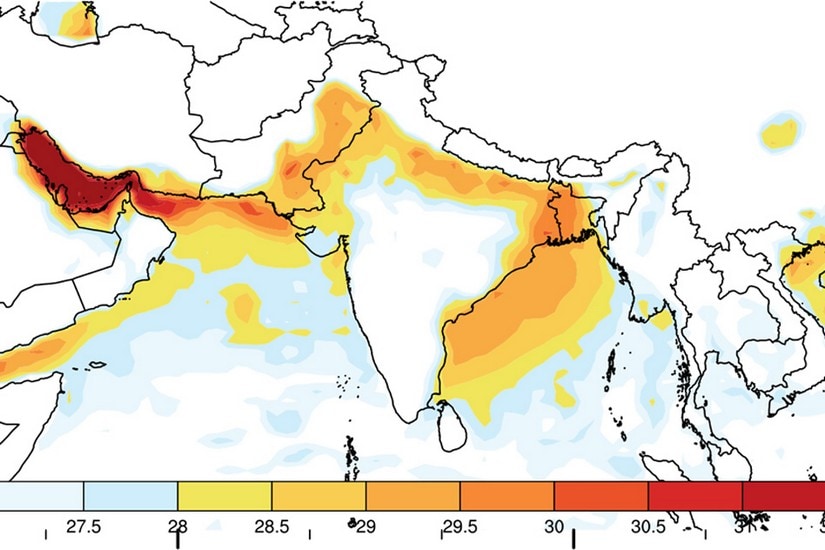

Regions of maximum heat stress in the country (more precisely: maximum “wet-bulb

Regions of maximum heat stress in the country (more precisely: maximum “wet-bulb

temperatures”). The entire Gangetic plane including Kolkata and the Sundarbans are already

among the most heat-stressed parts of South Asia. Image:

Courtesy of the researchers

[/caption] Q&A: How heat stress is measured: The “wet-bulb temperature”. When ambient temperatures are high, the human body cools itself through perspiration by regulating sweat. Water in the sweat evaporates by absorbing heat from the body. While the body controls the sweat glands, the rate of evaporation is limited by the saturation level of air. The closer air is to 100 percent humidity, the slower is the rate of evaporation, compromising the ability of the body to cool itself, thus causing heat stress. A quantitative measure of heat stress is called the wet-bulb temperature that expresses the combined effect of temperature and humidity on the human body. Prolonged exposure to a wet-bulb temperature over 30 degrees Celsius is considered very dangerous and likely to provoke heat strokes, especially among outdoor workers and the elderly. At a wet-bulb temperature of 35 degrees Celsius, it is physiologically impossible for the human body to cool itself. Exposure for even a few hours is fatal regardless of age and health. Presently, wet-bulb temperatures even during the most extreme heat waves on land rarely exceed 32 degrees Celsius, but worst-case climate change scenarios may see many parts of the world, including South Asia, regularly exceeding even the survivability threshold of 35 degrees Celsius within the lifetime of today’s children. Humid heat waves in the future: one of the gravest future concerns for Kolkata “The government schools were supposed to re-open on 20 June after the summer vacation, but will now open on 30 June,” West Bengal’s education minister Partha Chatterjee said last year. In the summer of 2018, the West Bengal government ordered schools to reopen

ten days later

than scheduled. The reason was the extreme humid heat that had gripped the state. In what is a cause for immense alarm for the city, recent

research led by Tom Matthews

published in the journal PNAS found that humid heat waves of the devastating intensity of those in 2015 may strike Kolkata on an annual basis for a global average temperature rise of “as little as” 1.5C. These temperatures will be met in about 20 years at the current rate of warming. Heat stress impacts children, the elderly and outdoor labourers the most, leading to the possibility of organ failures and heat strokes. It is an issue we will revisit in the last article in this series, in which Dr Dhires Kumar Chowdhury, a geriatrician based in Kolkata, speaks about the health impacts of climate change that he has observed over the years. The science is in and the threat is real. It is absolutely critical to quantify the risk that this entire region faces on account of heat waves. The people of Kolkata are recognizing these changes, even if it may not necessarily be clear exactly how much worse it is about to become. Kolkata cannot stave off this terrible future by attempting to mitigate global climate change in isolation. What is certainly within its means is mitigating some of the risk posed by climate change through urgent and innovative adaptation measures (

efforts in Ahmedabad

may serve as inspiration). Q&A: Why Kolkata? It is not immediately obvious why Kolkata should be vulnerable to intense heat waves in the future any more than, say, Mumbai or Chennai, both also hot and humid cities. In an email, Matthews hypothesised that humid air from over the Bay of Bengal flowing towards Kolkata during summer may be the reason for Kolkata’s seemingly larger propensity for heat waves. Testing this hypothesis will require the use of climate models (and Matthews suggested a methodology). Yet, it leaves open the question about Mumbai and Chennai. It is one of the general features about modern climate models that include so many detailed and interacting dynamic processes governed by physics, chemistry and biology (vegetation, for instance), that it can be difficult and time consuming to identify the exact reasons for specific projections made by the models. A rough analogy would be modern Operating Systems (MS Windows, Mac OS) that generally work well but whose complexity make it a difficult task to track down the source of a bug. The author is a climate physicist currently freelancing for Firstpost. You can get in touch with him on chirag.dhara@protonmail.ch

)