On a warm late-autumn afternoon, the sun slanted through the open stable corridors just beyond Gate no. 24 of the Rashtrapati Bhavan.

This is the President’s Bodyguard (PBG) lines, the heart of India’s oldest mounted unit, where an ancient tradition is lived, breathed, and meticulously maintained every single day.

Firstpost gained rare access to these exclusive stables within the presidential estate to understand the emotional and institutional meaning of the animals that form the mounted regiment.

Within this remarkable setting, where the most significant ceremonies of the world’s largest democracy are conceived and prepared, stand the horses — majestic, disciplined, and utterly central to the regiment’s identity.

The story of the PBG, therefore, is not merely a military narrative; it is an intimate tale of equine excellence, unbroken martial tradition, and a deep, almost spiritual bond between human and animal.

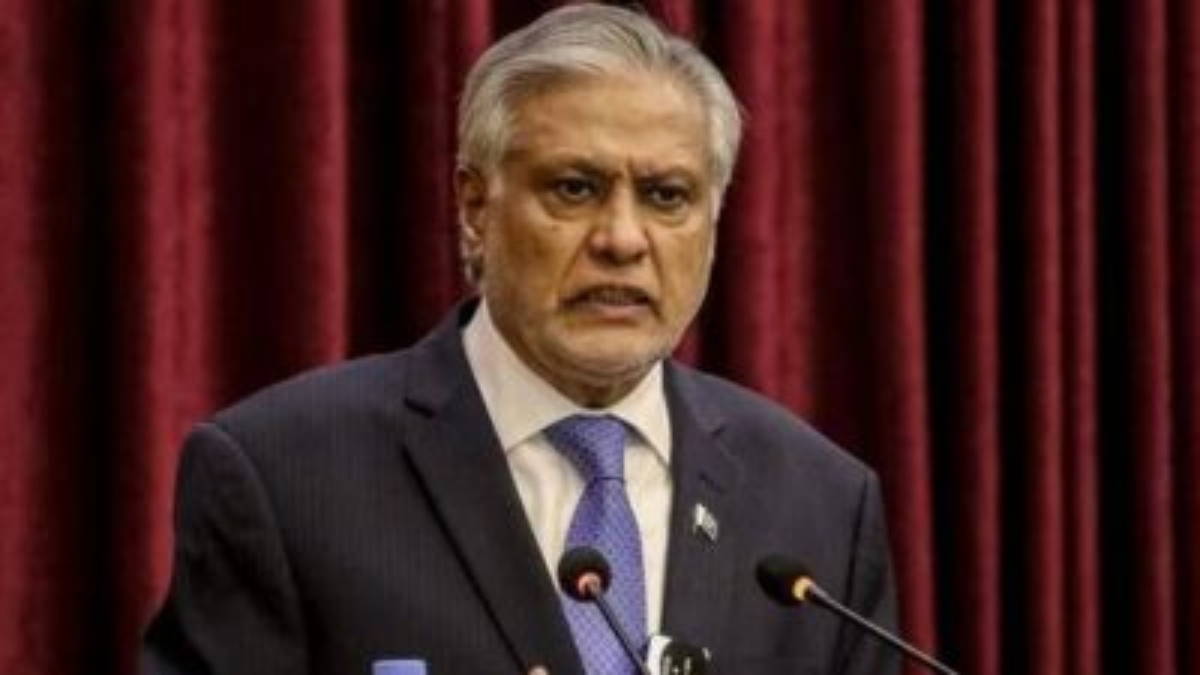

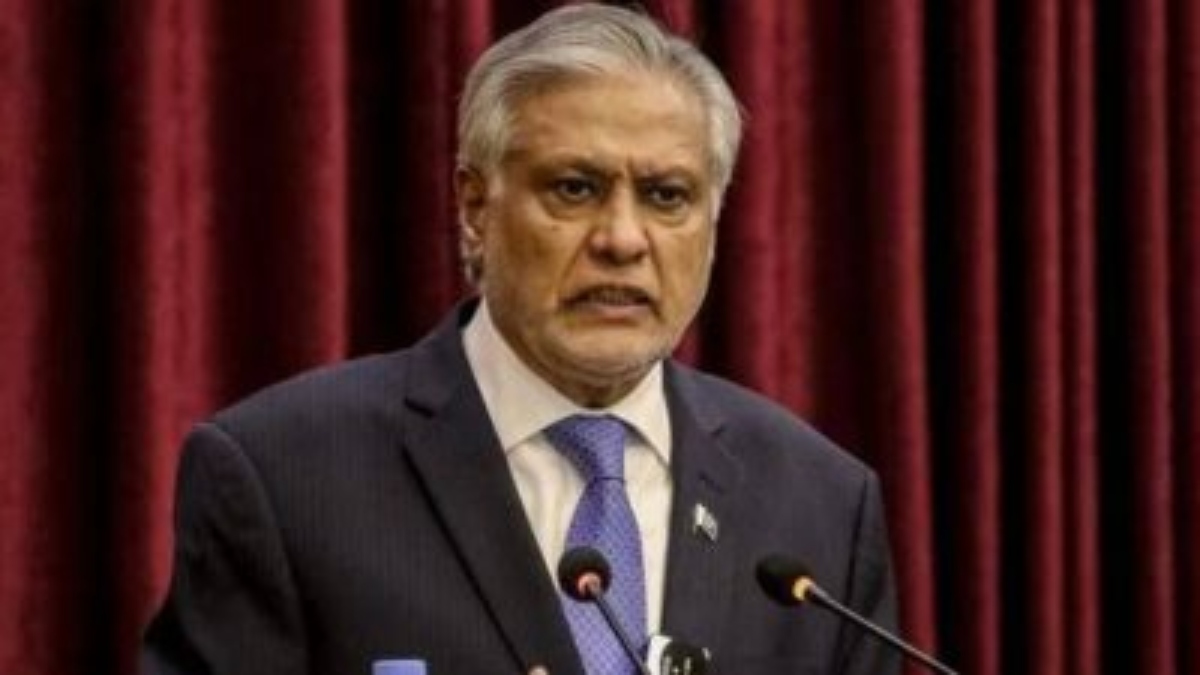

The insight into this unique world comes directly from Colonel Amit Berwal, Commandant of the President’s Bodyguard, who has been posted at the Rashtrapati Bhavan since February 2023, speaking to Firstpost’s Anmol Singla about the unit’s philosophy and future.

250 years of mounted dignity

The President’s Bodyguard is unlike any other military unit in India. It is the first uniformed presence visible to any incoming head of state, tasked with presenting an image of India’s poise, discipline, and historical grandeur.

This responsibility is carried on the backs of its ceremonial mounts.

The PBG is the oldest and senior-most unit of the Indian Army, maintaining the prestigious distinction as the ‘Right of the Line’.

It was originally raised in 1773 when Raja Chet [Chait] Singh of Varanasi (formerly known as Benaras) provided 50 horses and 50 men to the then-Governor-General Warren Hastings.

In 1950, after India became a Republic, the unit formally became the President’s Bodyguard, which coincidentally are now celebrating 75 years being designated as.

The PBG’s ceremonial role, while modern in its political context, is deeply steeped in this historical martial heritage.

The regiment stands ready to execute any critical diplomatic function during state visits at a moment’s notice, such as the arrival ceremony of a visiting head of state.

“We present the national salute, there’s a contingent of horses there and we have two and a half minutes to thereafter escort the incoming head of state in front of our Honourable President and the PM,” Berwal revealed to Firstpost.

The horses are the defining visual element of this moment. They must communicate India’s dignity, discipline, and power.

“So our salute, our drill, the disposition of our horses and the whole package must be such that the incoming person must get a sort of an introduction of what Indians are, what is India all about and you have to sort of make sure that the person is in awe of India.”

What makes a horse worthy of the President’s Bodyguard?

Not just any horse can carry the weight of the nation’s ceremonial duties. The PBG mounts are an elite class of their own, bred and trained for specific attributes that place majesty and composure above all else.

They are dramatically different from their more agile counterparts, the polo ponies.

These ceremonial giants, often Hanoverian and warmblood horses, are large, disciplined, and trained to remain unflinchingly calm amidst the flashing lights, deafening sounds, and massive crowds of national events.

Berwal stressed the required physical profile needed for this imposing ceremonial display.

“So our horses must be like that. They must be tall, handsome, big,” he noted.

The physical difference between a ceremonial mount and a sporting horse is stark, measured in hundreds of kilogrammes. The mounts are specially configured for precision and bearing, sacrificing the quick movements required for sport.

“They are at least 250 kgs heavier than a normal polo horse which you see,” the Commandant revealed. “Polo can’t be played on big tall horses because these horses have a different configuration.”

Ceremonial horses must move in slow, precise cohesion, commanding attention without betraying a single flicker of nervousness. Agility and acceleration, the core attributes of a battlefield or polo horse, are not their primary requirements.

The horse who became a national symbol

Every stable has its star, and in the PBG, that star is Virat.

A Hanoverian warmblood, Virat is 25 years old — an ancient age by Indian standards — and holds the distinction of being the most decorated horse in the regiment, a true legend.

The horse has stood before presidents, prime ministers, state dignitaries, and thousands of spectators along Rajpath for more than a decade.

“Virat has done 13 Republic Day parades,” Berwal shared, noting the immense pressure this involves, which includes “about 45 to 50 days of gruelling practise on tarmac.”

His exceptional service was formally recognised.

“He has been awarded a commendation card by the COAS [Chief of the Army Staff] in 2022,” Berwal said. The ultimate honour, however, came during one of the most visible moments on the national calendar.

“He’s been patted personally on parade during the 26th January celebrations by the then Honourable President and the PM.”

Retired at the age of 22, Virat now lives out his years in dignified, cherished comfort within the PBG stables, enjoying a “very special status” that is a testament to the regiment’s reverence for service.

But why is horsemanship still essential?

In an age of drone warfare and mechanised battalions, the emphasis on horsemanship within the Indian Army, and particularly the PBG, might seem anachronistic.

Berwal argues the exact opposite: equitation is not a relic; it is a vital component of leadership training. It is a training that allows soldiers to overcome fears and develop confidence by being in sync with a non-verbal animal.

“Any worthwhile army or institution in the world has got equitation as part of its leadership programme,” he asserted, citing even the training of civil servants at the IAS academy in Mussoorie.

The reason is simple and profound: interacting with a horse builds character essential for command.

“It lets you overcome your fears. It helps you become confident. It helps you understand an animal who cannot speak, be in sync with it, have empathy, sympathy.”

Horsemanship demands discipline, composure under stress, swift decision-making, and emotional restraint — traits that define a successful leader. The Commandant draws a direct line between equestrian skill and moral fibre, suggesting that riders possess an inherent gentleness and restraint.

“You will seldom come across good riders who are not gentlemen or who are not perfect ladies. They will seldom be irrational. They will always have a lot of sympathy, empathy, good people and horses have a good role and an effective role to sort of shape their personalities.”

Where does polo in the PBG come in?

If ceremony is the PBG’s external display, then polo is its internal laboratory — a continuation of martial lineage disguised as a sport.

Polo has been inseparable from the Indian cavalry tradition for centuries, having originated as a traditional sport in Manipur and Ladakh before being formalised by the army.

Berwal, a top polo player himself, explained that the army adopted polo because it provides an excellent opportunity to train a rider and a horse to the situations they might face on a battlefield, demanding agility, balance, timing, coordination, and situational awareness.

Even after cavalry charges vanished, the sport’s utility for training readiness persisted.

It simulates the chaos of war — demanding rapid acceleration, sudden turns, balance, timing, and split-second intuition between rider and mount.

Today, the PBG is actively working to restore its standing in the sport.

“We are now trying to revive polo in the PBG after a short gap,” the Commandant stated.

Till date, coinciding with the Indian polo season, the President’s Bodyguard (PBG) Parade Ground witnesses the President’s Polo Cup every year, attended by none other than the President of India.

This revival is significant, signalling a renewed commitment to a tradition that saw the Indian Polo Association itself operate from within Rashtrapati Bhavan until 2004.

How are polo ponies different from PBG’s ceremonial mounts?

The polo horses needed for this revival are a different breed entirely.

They must be configured for speed and agility, not bulk.

The Commandant noted that competitive polo horses require a short turning radius, explosive speed, and the ability to stop instantly.

“For polo you need a very agile, flexible horse with a very short turning radius, a horse which can almost instantly stop, turn back on its hind quarters again with an exploding speed, and accelerate rapidly,” Berwal explained.

To achieve this level of competitive speed, the PBG is strategically adapting its breeding and procurement policies. Traditionally, the army relied on its own bred horses, but the need for competitive quality is leading to a new approach involving faster lines.

“We are now being permitted to look at thoroughbreds to play for polo. I am sure in times to come we should be able to produce speed and quality of game which is now available in the city street,” he told Firstpost.

This strategic ambition is supported by the highest levels of the institution, ensuring alignment between ceremonial duties and sporting goals.

“There is a lot of support from the army… and we have all the required support from Rashtrapati Bhavan for all initiatives which are in good faith for the welfare of horses and for the welfare of troops.”

How are horses tended to at the PBG stables?

Beneath the gleam of ceremonial brass and the blur of the polo field lies the quiet foundation of the entire institution: the relationship between the rider and the horse.

This relationship, according to the Commandant, is one of total, dependent trust, exceeding professional routine.

“Tending to a horse is like tending to your child,” Berwal admitted. “The horse is completely dependent on the human athlete.”

He elaborated on the horse’s inherent vulnerability, pointing out that anatomically, they lack the offensive capability of carnivores.

“The horses don’t have claws… They don’t have nails… The horses don’t have canines like the carnivores. They can bite you but they can’t bite you to kill you and eat you.” Their evolutionary instincts favour flight, not fight, making the rider the ultimate protector and guide.

Its survival, especially in stressful or chaotic situations, hinges entirely on the human rider’s judgement, composure, and care.

“So, if the rider and the horse are in unison, they can do wonders. That is the kind of care which you must give to the horse and that is the kind of care which the horse expects.”

The consequence of a lapse in this bond is immediate and profound, leading to loss of performance and trust. “If there’s a disconnect, then there’s loss of performance. There’s loss of faith.”

This high-stakes dependency — in which a horse will only stop when it physically “cannot move any further” — makes the PBG’s daily routine a continuous practice of responsibility.

What happens to the horses after service?

A common public misconception is that old military horses are disposed of or euthanised. Berwal categorically dismissed this notion, stating the institution’s commitment to dignity in retirement.

“No, it doesn’t happen,” he said plainly.

“A horse dies as peacefully and naturally as possible… just like a human being. As we see, our elders pass away, a horse passes away like that unless he’s ill.”

Once they retire from service, army horses are sent back to their original depots.

“They lead a retired life. They are not subjected to work. They get their rations and food and they’re free to graze,” ensuring their final years are lived in quiet peace and comfort.

And in the end, the ultimate sign of respect is afforded.

“Horses are buried,” he stated simply, maintaining a standard of honour anchored in profound respect for an animal that has given its life to the service of the nation.

The horses are not simply ornamental; they are functional assets essential for maintaining the constitutional dignity and diplomatic spectacle required of the world’s largest democracy.

The unit’s continued excellence in drill, equitation, and leadership training confirms the functional relevance of the mounted regiment in the 21st century.

At Firstpost, we extensively covered Indian polo through the 2024-25 season, first focusing on the origins of the sport, and then diving deep into the role of the Indian Armed Forces in reviving polo as well as the challenges the sport faces in the subcontinent.

Now we have begun with a new series of features focusing on the 2025-26 Indian polo season.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)