Policy is a manifestation of astute follower-ship, a balancing act — an act of judgement of which action from a plethora of possibilities will work to address the problem (and in some cases seen to address the problem), and gain (or at the very least not lose too much) democratic gratitude of a section of society that votes. Three resources used in solutions are money, cross-functional, local expertise in generating effective solutions, and political capital required to choose and implement a solution. I would argue that any solution needs to score high on the third resource to be adopted. The winter North Indian pollution crisis, aka the Delhi Pollution crisis, provides a timely example to test this theory. Despite the millions of lives being affected, this problem is not getting any better. However, behind the scenes, something is moving. Tourism suffers – who wants to wheeze on a vacation? Those who can move, move; Urban Clap, an online marketplace of on-demand home services, is said to be

building up a second headquarter in Bengaluru. Start-ups are building technologies that address this (including my investee companies — Nanoclean and Chakr Innovation). Lobbying efforts intensify. Longer-term, politically-feasible solutions are implemented. But, the problem does not appear to be getting much better. There are two factors behind this that have little to do with politics or policy. Identifying Herbie – the data To solve manufacturing issues, one often conducts a de-bottlenecking exercise. The Goal by E Goldratt speaks of a protagonist guiding a group of schoolboys on a hike. The boys are too slow. By observing the gap between the boys, the protagonist realises that the group can only move as fast as the slowest walker, Herbie. But, if he can make Herbie walk just a little faster (by distributing the weight of Herbie’s backpack with the other boys), the whole group speeds up. Essentially ‘Herbie’ represents the one process (or thing or person), whose performance improvement can have dramatic impact on the overall process. What is the Herbie in solving the winter air pollution crisis? To identify our Herbie, we need data. China had excellent, hourly, source-apportioned data for its cities and neighbourhoods. This, along with a different political reality, helped the country to significantly address its air pollution issue. India has overall PM 2.5 levels available by location, which gives us no idea of which source is driving the pollution. CEEW’s

brief on emission inventories lays out the uncertainties in current efforts to understand the sources of the pollution. Such uncertainty can be hijacked by vested interests to ensure effective policy is delayed or diluted. I cannot overstate the importance of accessible, clear robust data in enlisting public support, and thereby political support. China’s battle against air pollution received a great shot in the arm by the documentary Under the Dome, which made the pollution data accessible, and was viewed, by some accounts, a 100 million times within two days of its release. India does not have hourly, source-apportioned data across cities and neighbourhoods in an accessible format. Which means we all don’t publicly agree on who our Herbie is. This obfuscates public understanding and dilutes political will. Dispersed pain, short attention spans Einstein put it well when he defined insanity as doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. We have a wonderfully choreographed cotillion in place: October, silence in the media, paddy harvests begin. Fields begin to burn. October end: Diwali. October/November: Meteorological changes; winds die down, temperature falls, vertical mixing decreases. November/December: wheat planting continues; media attention peaks and shrills, ‘noted public figures’ begin to tweet, political bickering notches up, gas masks are donned, air purifier sales increase, knee-jerk policy (primarily of the seen-to-address variety) ensues, health deteriorates, flights delayed/cancelled, prayers for rain and wind increase. January: tapering begins. Put another way, the charade looks like this:

![delhi-pollution-1]()

This is the Google trends report on air pollution in India with ramifications for political decision making. Tough decisions are hard because they have to overcome vested interests by continually exercising political will. The kind of staccato concern we show on air pollution cannot compete with the sustained focus of lobbying efforts. There is enough funding available in the private sector, whose lives are affected by the pollution, to fund the infrastructure necessary to get the needed data. Sequencing is important here. Unless and until we fix data/public interest, it is highly unlikely that meaningful solutions will be found. What we will get is half-baked do-nothing policy. Or, in the words of my erstwhile colleague, ‘rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic’. Policy action (the realm of government) follows, not leads. Even with the data we have, what is the Herbie? It’s the money Two causes stand out in the emission

inventories: vehicular emissions, and the one responsible for the winter pollution spike — biomass burning. Let us deal with the latter today, and leave vehicular emissions for another time. The

financial embrace between the government and the farmer is complex. The farmer’s income is determined by procurement, the Minimum Support Price (MSP) scheme, fertiliser, electricity and interest subsidy, and, of course, skill. Access to these schemes is

typically lop-sided with well-connected farmers walking away with a lion share of benefits. While that becomes important later, for now, let us understand that the farmer, much like the baker and the butcher of Adam Smith, is acting in his self-interest when he chooses to grow paddy and wheat. Why? Food subsidy In 2018-19, the food procurement subsidy allocated to the Food Corporation of India (FCI) was Rs 140098 crores. Wheat and Rice account for 99 percent of the grain procured by FCI.

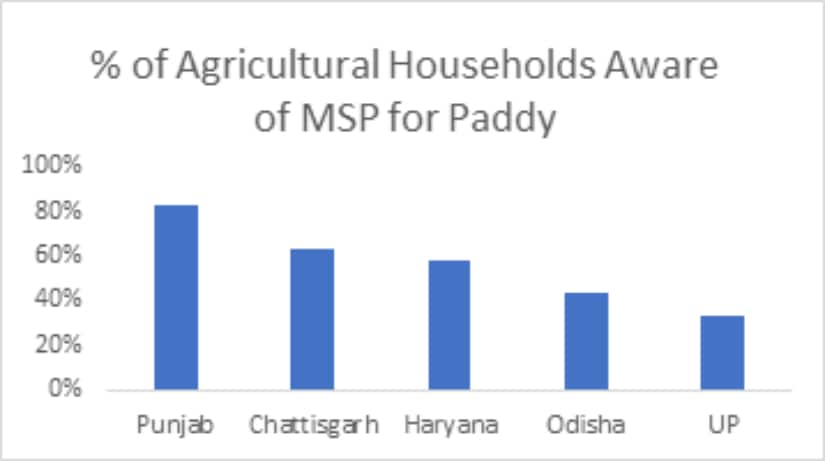

Punjab and Haryana rank among the biggest beneficiaries of this subsidy – given that they supply 58 percent of the rice and 68 percent of the wheat procured by FCI. As a rough ballpark figure, 60 percent of the subsidy works out to Rs 84000 crores. Great procurement – no market risk Ironically, paddy burning in Punjab and Haryana results from the local government in those states doing their job – extension, procurement and payment – very very well. Farmers are both aware of Minimum Support Price (MSP) and are able to sell their crop at that price – a rare thing in India (See Figure 1 and Figure 2). [caption id=“attachment_7612611” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Percentage of agricultural households aware of MSP for paddy, Kharif 2012; Source: Some aspects of farming in India, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_7612621” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

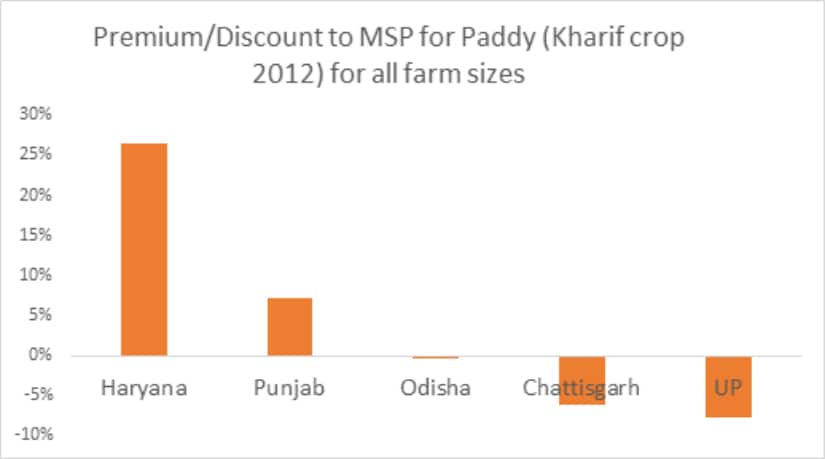

Premium/Discount to MSP for Paddy, 2012; Source: Some aspects of farming in India, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation; Note: The premium for the smallest farmers, ie those with < 0.5 Ha land seems abnormally high in Haryana, which distorts the overall premium for Haryana[/caption] Haryana’s procurement is so damn good, that

farmers from other states sneak in to sell their paddy at the Haryana mandis. For farmers in this state, there is little market risk or marketing effort required to offload their paddy and wheat – an important point to keep in mind as we lament about crop diversification. Fertiliser subsidy Punjab and Haryana’s share of the Rs 70,000+ fertiliser subsidy

works out to over Rs 8000 crores. Moreover, the incentive to convert stubble to compost is dampened when free fertiliser is available. Power subsidy and UDAY – all carrot, no stick The 2018-19 power subsidy for farmers in Punjab is

budgeted to cross Rs 6000 crores. Haryana’s equivalent

was Rs 5933 crores in 2016-17. Not all of the subsidy flows to farmers growing wheat and paddy of course, but most does. There is an added nuance here: the Punjab government

signed up for the UDAY scheme in 2016, whereby the Punjab state government would take over part of the debt of the state electricity board (resulting in cheaper financing), in return for operational efficiency. However, what happened is different. Punjab’s UDAY dashboard tells a disturbing story –cheaper bonds have been issued and both the Punjab state government and the Punjab state electricity board have financial breathing space. But, the other side of the

MOU has not seen movement. The MOU states: “Punjab DISCOM will endeavour to reduce AT&C losses from 16.66% in FY14-15 to 14% by FY18-19”. In reality, AT&C losses have ballooned to over 30 percent! UDAY has lessened the pain of free electricity to the State, without the necessary operational tightening. All carrot, no stick. Expertise and extension Lastly, Punjab farmers in particular, are experts at growing paddy and wheat, thanks in part to great extension support from Punjab University, which results in substantially higher yields. A one lakh crore subsidy Putting all this together, in 2019, farmers from Punjab made a premium of Rs 10 per kilogram of paddy, substantially more than the premium of the average Indian farmer — Rs 5.8 per kilogram. The cost base here is A2+FL cost, which is fertiliser, pesticides, hired labour, seeds etc plus an imputed cost for family labour engaged. A one lakh crore subsidy coupled with efficient procurement and skill ensures that the farmers of Punjab and Haryana will grow paddy and wheat while their water lasts. Money talks. The eloquence of this financial calculation manifests in the falling water table of the Punjab, and the smoky skies over North India. The Supreme Court has recently weighed in, saying the state and the local bodies should be held accountable for stubble fires, on the Polluter Pays principle. Subsidy/fine/subsidy/pollution. What a mess. What problem are we trying to solve? There is a larger point to made here, we will optimise what we focus on. If we want to optimise water use and soil health and lower pollution, we must change crop patterns. This is a map produced using WRI’s India water tool. The angry red of Punjab and Haryana, with little local rainfall, is almost entirely due their crop choice and irrigation practices incentivised by the MSP, procurement efficiency and practically

free electricity.

![delhi-pollution-4]()

If our problem statement was ‘How to reduce the impact of pollution from stubble burning’, the obvious starting point, or the Herbie, appears to be changing crop choice.

![delhi-pollution-5]()

We could do that by removing subsidies, right? While there have been rumours that the Rs 70,000 crore fertiliser subsidy might be tapered down, a recent government

press release opened unequivocally: “There is no proposal to cut Fertilizers Subsidies.” Influencing crop choice by pricing electricity is also a non-starter. Punjab’s Chief Minister has been recently

quoted as saying: “his government was committed to the supply of quality power, in addition to 100% cost subsidy for agriculture and free power to various categories of consumers.” On the contribution of his state to the North Indian pollution crisis, he

tweeted: “Compensation by Central Govt to the farmers for stubble management is the only solution in the circumstances. I had written to PM @NarendraModi ji on 25th Sep & had written to him yesterday as well. The central govt has to step in and find a consensus to resolve the crisis.” The central government could step in and say no more MSP. Or, for less of a shock, say MSP applies to only those farms that don’t burn (tackles pollution but not water). This expends political capital in a limited fashion, and may be far more effective than the solutions peddled today. All these options are cheap in terms of ‘money’, but profligate in terms of political capital required. They don’t happen because the bottleneck resource is not money, it is political capital. When we optimise political capital, the problem we are trying to solve is: ‘What is the politically cheapest solution seen to address air pollution caused by stubble burning.’ Very different problem statement. Accordingly, today’s solutions play about in the margins. One of these is the Happy Seeder. The problem in paddy fields begins when the combine harvester harvests the rice but leaves a few inches of stalk standing. Farmers would burn the remaining stalks (stubble) to clear the fields for their wheat crop. The Happy Seeder cuts and lifts the standing stalks, spreads them over the entire field and plants the wheat seeds. It addresses the labour and the urgency issues in gathering the stubble. But it is an added cost in the eye of the farmer. The government gave a subsidy – an allocation of Rs 1151.8 crores (fully funded by the Centre) – towards machinery capital subsidy, awareness and setting up Farm Machinery Banks. Expensive, credible, and seen to address stubble burning. But, the subsidy given was a capital subsidy – which predictably increased the price of the machine (by some accounts almost doubled it). Smaller farmers did not find it accessible – Rs 70,000 (even with the subsidy) is a lot of money for a smaller farmer. Farmers also complain that using the machine is too expensive (the combine harvester needs an additional straw management system for the Happy Seeder to work well, which sucks up more diesel) and that they should be paid another subsidy to not burn. Other solutions include alternate uses for straw including biogas, pellets for thermal plants or even cutlery. But the prerequisite for all of these is an efficient and cheap logistics network that can collect straw from thousands of farms in the span of two weeks. Not impossible, but not easy. At least, not until fertiliser subsidies lower the attractiveness of substitutes. Sameer Nagpal, who runs Sampurn Agriventure, the only biogas plant in India that works off paddy straw, cites several issues in scaling up. One is that the economics of his biogas plant work only if he sells the compost it generates as a by-product. Organic compost is among the most expensive (and effective) fertilisers available. But farmers, traditionally fearing a new face, are wary of buying expensive black ‘stuff’ from a new entrant, and can, moreover, make the compost themselves. The other is that the current power purchase rates offered by state electricity boards do not cover the costs. In late-2018, the Indian government introduced the SATAT, or the Sustainable Alternative Towards Affordable Transportation, initiative that looks at a decentralised model for biogas with committed offtake by a large petroleum company like IOC. The has made the economics of biogas more compelling, which is a positive sign. The bottleneck remains logistics, or the financial incentive for creating the logistics infrastructure. Something that today’s subsidy regime is clouding. The impact of the peripheral measures in the time series of images from NASA FIRMS from 2017 to 2019 from 15 October to 4 November in each year*****: [caption id=“attachment_7612671” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

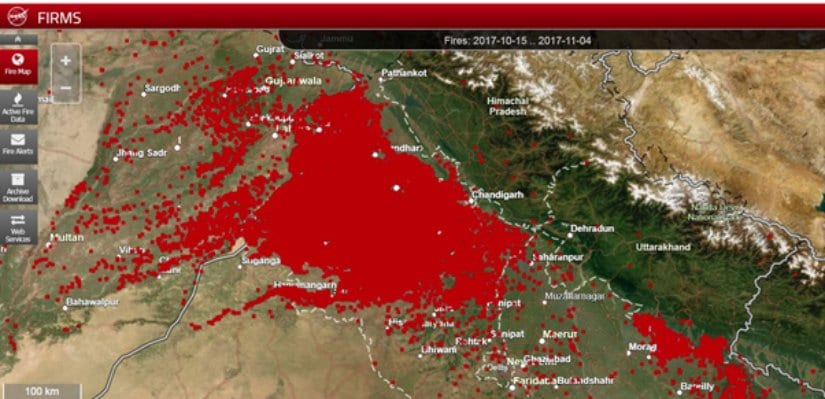

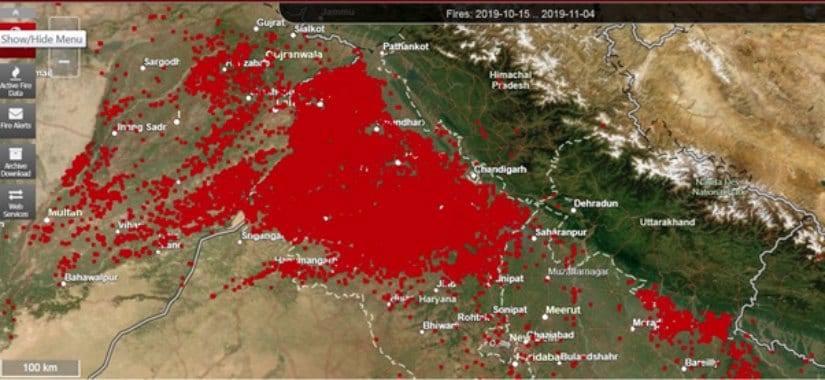

NASA Firms Image of 2017 fires between Oct 15 - Nov 4[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_7612681” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

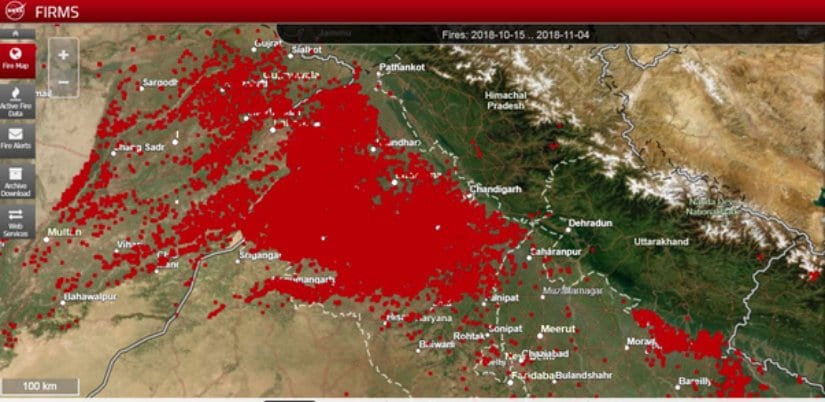

NASA Firms Image of 2018 fires between Oct 15 - Nov 4[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_7612691” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

NASA Firms Image of 2019 fires between Oct 15 - Nov 4[/caption] Negligible reduction. Let’s be clear: Only granular, frequent, source-apportioned, publicly-accessible data will reveal the true ‘Herbie’ to all constituents. This will (hopefully) engender the unwavering public attention, which will strengthen political will to take action on the true ‘Herbie’. Everything else is waffling. *****We acknowledge the use of data and imagery from LANCE FIRMS operated by NASA’s Earth Science Data and Information System (ESDIS) with funding provided by NASA Headquarters The writer is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, cleantech angel investor and author of

The Climate Solution — India’s Climate Crisis and What We Can Do About It published by Hachette. Follow her work on her

website; on

Twitter; or write to her at

cc@climaction.net.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)