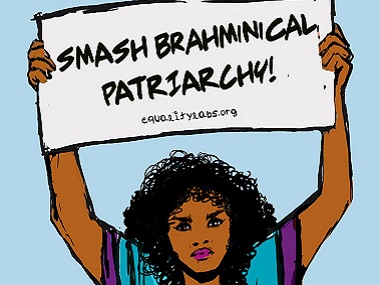

Editor’s note: A photo of Twitter CEO holding a poster that read “Smash Brahminical Patriarchy” — it was presented to him by activist Sanghapali Aruna during a meeting in Delhi — stirred up strong reactions on social media. Debates over how casteim and patriarchy operated in India ensued, as did discussions over whether or not Dorsey’s posing with a poster was an example of hate speech, whether Brahmins were being targeted, and the semantics of the term Brahminical (or Brahmanical) patriarchy. In this debate, we ask the question — ‘Is Brahmanical patriarchy just a slogan?’ Arguing against the motion is Vasudha Katju, who teaches Gender Studies at Ambedkar University, Delhi. Katju points out that the term offers a meaningful way of talking about the relationships between gender, caste, the economy, and the state. Read the counterpoint to this debate by Shrikanth Krishnamachary here . *** To say that ‘Brahmanical patriarchy’ is just a slogan implies that this term has no meaning: it is catchy and memorable, but doesn’t convey anything. However, I find that ‘Brahmanical patriarchy’ conveys ideas that are deep and complex. It describes how we live in societies that are shaped by gender, caste, and economic relationships, and in turn shape them through our decisions and actions. Many of us know that women face various disadvantages in a society structured in ways that give men power while withholding it from women. We have seen statistics on sex ratios, on malnutrition, on violence; we hear of schemes to save the girl child or campaigns to prevent gender-based discrimination. We believe there should be equality between men and women. We may relate to these ideas at a personal level. We have faced and witnessed sexism, harassment, domestic violence, discrimination. Often, a term like patriarchy does not teach us something new but rather affirms and gives a name to something we already knew. Brahmanical patriarchy has a similar effect. It adds to our knowledge, and also gives us a language to identify and give voice to our experiences. [caption id=“attachment_5664841” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  (L) The Smash Brahminical Poster that went viral. Image via Twitter/@dalitdiva; (R) The meeting at which Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey was gifted the poster. File Photo[/caption] Brahmanical patriarchy is a way of talking about the relationships between gender, caste, the economy, and the state. These relationships have been examined by various scholars over the decades. Dr BR Ambedkar, in his 1916 paper, ‘Castes in India’, pointed to endogamy (the principle or custom of marrying within a particular group) as the basis of the caste system. Endogamy worked through the practices of sati, enforced widowhood, and ‘girl marriage’ (what we today would term child marriage). Control over and regulation of women’s sexuality is, in his account, the basis of the caste system. Uma Chakravarti, who coined the phrase ‘Brahmanical patriarchy’, has examined how, in ancient India, the control of land (an economic asset) by certain caste groups, is maintained through similar regulations over women’s sexuality which are sanctioned by the state. Padma Velaskar has described how, within the village economy, certain jobs and tasks are divided between women of different caste groups. ‘Brahmanical’ patriarchy does not mean patriarchy in Brahman castes. Rather, it refers to the particular form of patriarchy in societies organised on the basis of caste. While the term has been theorised through examinations of Brahmanical texts, it offers insights into current social practices. All this might seem very abstract. Yet I have found that the term conveys ideas which help me to understand both my own life and the world around me.

Taking Brahmanical patriarchy seriously requires a shift in focus, away from ourselves as individuals, to ourselves as part of groups — families, castes, religious communities, genders, classes, nations. It requires us to acknowledge that our experiences are shaped not just by our being men or women, but by being men and women of certain castes, classes, and communities.

It requires us to think of how our actions reproduce those communities. It requires the recognition that our most personal decisions — what to study, what kind of a job to do, how to dress, what to eat, whom to marry, if and with whom to have children — have implications that go far beyond us. It requires me personally to think of why, while I was growing up, I never considered that I would have a job that required me to work with my hands. It makes me wonder why I have always assumed that a single woman who wants to be a mother would consider adoption before bearing a child. Also read: The story of Jack (Dorsey) and the smashing (Brahmin) backlash, told in memes ‘Brahmanical patriarchy’ appeals to me because it makes me ask certain questions which I otherwise might not have asked. For example, why should governments that have overt commitments to combating violence against women, hesitate to criminalise marital rape? Why should they wish to prevent women from accessing an equitable division of household assets upon divorce? Why should families, hostels, and paying guest accommodations be interested in restricting women’s mobility? What credence can we give to arguments that restrictions are placed on women for their own safety? Women students across the country have reported instances where hostels and PGs locked them out at night when they returned after the curfew. Did this make them safer? In another case, a PG owner refused to unlock the gate during an earthquake. Were the residents who remained trapped within the building safe? The perspective that Brahmanical patriarchy offers is difficult to accept. We tend to think of ourselves as capable of making our own decisions and thinking for ourselves. It’s hard to counterbalance this self-image with the idea that our tastes, desires, ambitions, choices, and decisions are shaped by wider social patterns that we often cannot even identify, let alone combat. It’s even harder to accept that sometimes, we will identify these patterns, recognise the harm they do to us and to others, and yet not change. Yet its strength is that points us in certain directions, which, if we take them seriously, will help us to examine our own lives. I do not use this term because it has all the answers. On the contrary, I appreciate it because it opens up the world in a new way – one that is challenging and painful, but might one day be liberating. The writer teaches Gender Studies at Ambedkar University, Delhi

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)