One hundred and fifty years ago, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay penned a poem, titled Vande Mataram, which translates to “Mother, I Bow to Thee”. It was first published in the literary journal Bangadarshan on November 7, 1875.

Later, it was set to music by Rabindranath Tagore and become an integral part of the nation’s civilisational, political and cultural consciousness. Years later, in 1937, the Congress adopted a modified version of Vande Mataram as the country’s national song, and in 1951, it was adopted by the Constituent Assembly at the instance of Rajendra Prasad as the national song, while Jana Gana Mana was designated the national anthem.

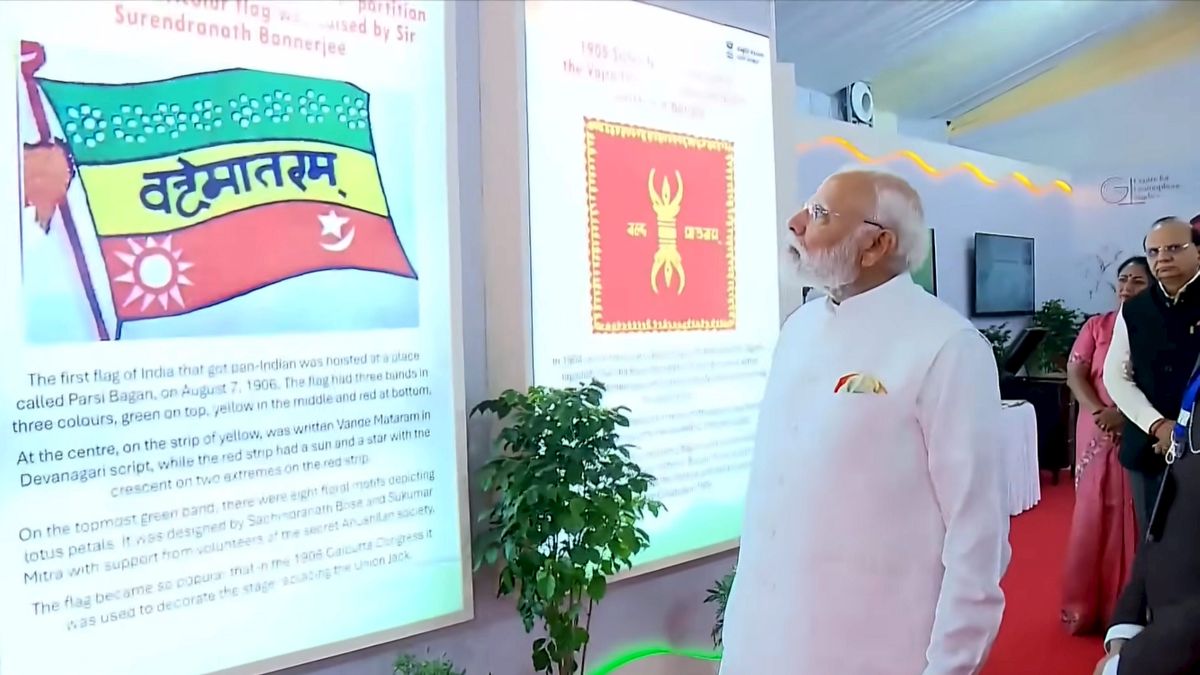

Now, after so many years have passed, on Monday (December 8), Parliament is holding a special session on the song, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi leading the charge for the government in a special session starting at noon in the Lok Sabha, while Home Minister Amit Shah will take up the matter in Rajya Sabha, the upper house, on Tuesday.

But why has the song that was penned years ago become a topic of discussion in Parliament?

The Vande Mataram debate in Parliament

To commemorate 150 years of Vande Mataram, Parliament earmarked time to have a discussion on the national song in Lok Sabha as well as in Rajya Sabha.

Lok Sabha, the lower house of Parliament, set aside a 10-hour discussion on the matter with Prime Minister Narendra Modi beginning the discussion at noon.

In his remarks, Modi accused the Congress of breaking the song under the guise of social harmony, and said it was still following the politics of appeasement.

He cited a letter written by Jawaharlal Nehru to Subhas Chandra Bose claiming that the background of Vande Mataram could antagonise Muslims. He said the letter was written following a protest by Mohammad Ali Jinnah in Lucknow.

Quoting the letter, Modi said, Nehru had written that he had read the background of the song and it could spark anger amongst Muslims.

He alleged, “On October 26, Congress compromised on Vande Mataram. They broke it into pieces under the mask of social harmony, but history is witness… This was Congress’s attempt at politics of appeasement. Under pressure of politics of appeasement, Congress agreed to divide Vande Mataram… This is the reason Congress also bowed to the demand for partition.”

The debate, in Parliament, titled ‘Discussion on the 150th Anniversary of National Song Vande Mataram’ forms part of the government’s ongoing year-long commemoration of the iconic poem written by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee. “Many important and unknown facets related to Vande Mataram will come out in front of the nation during the debate,” a senior government official said.

A similar debate will also be held in the Rajya Sabha, albeit tomorrow (December 9) with Home Minister Amit Shah leading the discussion followed up by Leader of the House JP Nadda.

Reason behind the debate in Parliament

The Vande Mataram debate in Parliament stems from the charge made by Prime Minister Modi that the Congress “removed important stanzas” from the song, thereby “sowing the seeds of partition”.

In November, the PM sharply criticised the Congress, claiming: “Vande Mataram became the voice of India’s freedom struggle, it expressed the feelings of every Indian. Unfortunately, in 1937, important stanzas of Vande Mataram… its soul was removed. The division of Vande Mataram also sowed the seeds of partition. Today’s generation needs to know why this injustice was done with this ‘maha mantra’ of nation building. This divisive mindset is still a challenge for the country.”

He added further that Vande Mataram was not merely a word but a mantra, an energy, a dream, and a solemn resolve. “This one phrase takes us back into history. It fills our present with self-confidence and gives us the courage to believe that there is no goal that Indians cannot achieve.”

Earlier, members of the BJP also alleged that the Congress had “brazenly pandered to its communal agenda under Nehru”, adopting only a truncated version of Vande Mataram as the national song.

BJP spokesperson CR Kesavan in a lengthy X post wrote, “It is imperative for our younger generation to know how the Congress party brazenly pandering to its communal agenda under the presidentship of Nehru, adopted only a truncated Vande Mataram as the party’s national song in its 1937 Faizpur Session.

“…The glorious Vande Mataram became the voice of our nation’s unity and solidarity, celebrating our motherland, instilling nationalistic spirit and fostering patriotism. Chanting it was made a criminal offence by the British. It did not belong to any particular religion or language. But the Congress committed the historic sin and blunder of linking the song with religion. Congress under Nehru citing religious grounds deliberately removed stanzas of Vande Mataram which hailed Goddess Ma Durga.”

It is imperative for our younger generation to know how the Congress party brazenly pandering to its communal agenda under the Presidentship of Nehru, adopted only a truncated Vande Mataram as the party’s national song in its 1937 Faizpur Session , while PM @narendramodi ji today… pic.twitter.com/13NBta11OV

— C.R.Kesavan (@crkesavan) November 7, 2025

He added that while Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose was in favour of releasing the song’s “full original” version, Nehru thought that Vande Mataram was “not suitable” as a national song. “On October 20, 1937, Nehru wrote to Netaji Bose claiming that the background of Vande Mataram was likely to irritate Muslims. He went on to say that there does seem to be substance regarding outcry against Vande Mataram and people who are communalistically inclined have been affected by it.”

The Congress, however, rejected this allegation, referring to the 1937 Working Committee decision that involved Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, Subhas Chandra Bose, Rajendra Prasad, Maulana Azad and Sarojini Naidu.

The CWC noted that only the first two stanzas of Vande Mataram were usually sung while the remaining contained religious imagery that some objected to. The Congress in its defence said that the decision was taken to ensure unity within the freedom movement. It also referred to a letter sent by Rabindranath Tagore to Nehru in which the former urged that only two stanzas be used.

The Congress further accused PM Modi of distorting history and of attempting to divert attention from current national issues.

Moreover, Congress president Mallikarjun Kharge added that his party has been the proud flagbearer of Vande Mataram, which awakened the collective soul of the nation and became the rallying cry for freedom, whereas BJP and RSS have “avoided” the national song despite its universal reverence. “RSS and BJP, who claim to be self-proclaimed guardians of nationalism, have never sung “Vande Mataram” or the national anthem, “Jana Gana Mana”, in their shakhas or offices,” Kharge claimed.

Vande Mataram — from rallying cry to national song

But what exactly is the history of the national song?

It is reported that one day, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, a civil servant by day, who was inspired by the Sanyasi Rebellion and Revolt of 1857, penned the words of Vande Mataram while sitting in a white house by the Hooghly river.

It quickly became popular and by 1905 became a rallying call during the Swadeshi agitation in Bengal. Rabindranath Tagore himself led nationalist protest processions in which Vande Mataram was sung.

In 1915, Mahatma Gandhi addressed a meeting in Madras that opened with the singing of Vande Mataram. Gandhi remarked: “You have sung that beautiful national song, on hearing which all of us sprang to our feet. The poet has lavished all the adjectives we possibly could to describe Mother India… It is for you and me to make good the claim that the poet has advanced on behalf of his Motherland.”

According to professor Sabyasachi Bhattacharya by 1920, Vande Mataram was possibly the most widely known national song in India. It was translated into numerous Indian languages: Marathi (1897), Kannada (1897), Gujarati (1901), Hindi (1906), Telugu (1907), Tamil (1908), and Malayalam (1909).

But in the 1930s, some contested Vande Mataram, claiming it was idolatrous, as the Indian Express reported. Some argued that the song was incompatible with the secular ideals of the country. Among the strongest to object were Muslim League leaders, including Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Their argument was that Vande Mataram referenced Hindu goddesses such as Durga and Lakshmi.

Moreover, a Cabinet note written by Nehru in May 1948, reveals the reason he was in favour of Jana Gana Mana and not Vande Mataram to be the national anthem of India. “A national anthem is, of course, a form of words, but it is even more so a tune or a musical score. It is played by orchestras and bands frequently and only very seldom sung. The music of the National Anthem is, therefore, the most important factor. It is to be full of life as well as dignity and it should be capable of being effectively played by orchestras, big and small, and by military bands and pipes. It is to be played not only in India but abroad and should be such as is generally appreciated in both these places. Jana Gana Mana appears to satisfy these tests … Vande Mataram for all its beauty and history is not an easy tune for orchestral or band rendering. It is rather plaintive and mournful and repetitive. It is particularly difficult for foreigners to appreciate it as a piece of music. It has not got those peculiar distinctive features which Jana Gana Mana has. It represents very truthfully the period of our struggle in longing and not so much the fulfilment thereof in the future,” wrote Nehru.

He further added the language of Vande Mataram was “very difficult for an average person”, while Jana Gana Mana “is simpler though it is capable of improvement and some changes are necessary in the present context”.

As a result of this, the Congress, supported by Mahatma Gandhi and Nehru decided to adopt the first two stanzas and it was eventually recognised as the national song of India.

With inputs from agencies

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)