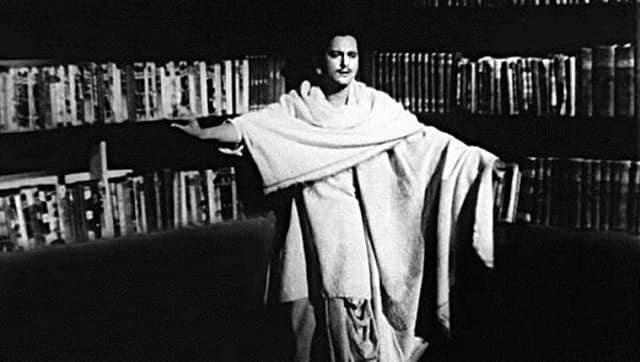

In what has to be one of the most memorable opening Hindi film visuals ever, we see Vijay [Guru Dutt], the protagonist of Pyaasa, lying on the ground, looking up at the sky, the birds, blissfully lost in his appreciation for nature. He flips around and notices a bee enjoying the nectars of a flower. He smiles at the bee’s joy. The bee then sits on the ground, and within seconds, we see it being trampled by a cold, indifferent foot. Vijay’s smile fades away. This whole segment lasts for 80 seconds, but Dutt so deftly captures the entire tone of his film here, and the rest of the narrative tries to capture this sole sentiment for the next 140 minutes — how we have lost the value for nature and art in this increasingly capitalistic society, how we have lost our soul perhaps. But this is also a rare film that addresses the dilemma. By their very nature, Hindi films have always had songs and poetry as a very integral part of their narrative. For the longest time, films have used songs to propel the story forward or merely staged a beautified dance sequence as an aesthetic breather amidst a dramatic narrative. These should be reliable signs enough, for our collective appreciation of artists. Our film stories have had space for artists as long as they add to the beauty and respite. However, the unrest of an artist living on their own terms has barely been the subject of our films. Pyaasa was a major box-office success, and yet it was not followed by many films about poets or artists, struggling or otherwise. In fact, the success of Pyaasa now seems like a rather surprising outcome, considering how bleak and hopeless it appears for most of its runtime. Now, consider this chain of events for once: A talented poet repeatedly fails to get his work published. He is eventually hired by a major publishing mogul, but as a butler. Later, the poet realises the mogul is his ex’s husband. While the poet does get a lot of affection from a streetwalker, his own family disowns him. A few days later, the poet is assumed to be dead because of his coat found on a beggar. Soon, his poetry gets published posthumously, and turns out to be a mammoth bestseller. The pre-climax unfolds at a packed auditorium celebrating the death anniversary of a man who is still alive, cashing in on someone’s fame they didn’t even know. [caption id=“attachment_10393631” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Guru Dutt in Pyaasa[/caption] A poet as a figure, a character has not often been someone found at the center of a Hindi film narrative, as someone with a conflict to resolve. For a conventional society, they are the conflict. In our real lives, we have often seen artists being treated as eccentric misfits who dance to their tunes, often holding contrarian views to the mainstream. Our boycott of them largely stays on the polite-yet-potent side — We do not outright banish them from society. And in Pyaasa, the symbolism is hardly subtle. Vijay’s humiliations never end — the mogul orders a subordinate to publish a soap advertisement instead of his poem. In another scene later, his poetry literally gets sold as raddi. And yet, Vijay refuses to pander or back out from his commitment as an artist. Vijay’s aversion to corruption even seems to extend to his ideas about sex, especially at a point when he looks resentful about a friend shooing from away after a visit from a prostitute. At that point, it does not feel wrong to label him a ‘prude,’ a conservative in the matters of desire. And yet, later it becomes clear why the idea of prostitution puts Vijay off so badly — he can see through the garb of seduction, and notices the exploitation that lurks underneath. Even when drunk, it becomes hard for him to ignore the realities, which others seemingly do so easily even in their complete senses, which comes out beautifully in his remorseful poem “Jinhe Naaz Hai Hind Par.” Vijay’s love for poetry symbolises his love for truth, even if it means wallowing in sadness, which it mostly does. And the world around Vijay does not have any time and patience for that. Vijay eventually even lands up at a mental asylum where his own people refuse to recognise him — but it makes sense. Pyaasa boasts of several technical and cinematic achievements, and yet that does not make it universal. What does is the portrayal of systematic boycott of a being who has consciously chosen non-conformity and be truthful to himself, his experiences.

As the films of later years proved, Hindi films have made increasingly lesser space for a poet as someone of value.

Our narratives have been far more generous towards other artists like singers, dancers, and musicians while ensuring that their involvement is never too political or socially conscious. Going by the Hindi movie manners, these artists are never supposed to be particularly morally conscientious in the first place. Their identity as an artist is merely to naturally peddle the musical element of the narrative [Teesri Manzil, Hum Kisi se Kam Nahin, Kaho Na… Pyaar Hai etc] — it changes nothing about their character or personality. A film like Akele Hum Akele Tum was a quiet exception where Rohit [Aamir Khan] struggles to pursue a certain, purer form of music in a world full of pandering and conformity. His stubborn, single-minded striving for excellence is what causes him misery. While the ’60s had films like Mere Mehboob and Chaudhvin Ka Chand that reveled in the aesthetic around poetry, the ’70s also reached a point where a hero had to declare ‘Main Shayar to Nahin’ [Bobby, 1975] before waxing eloquent about a beautiful stranger he just laid his eyes upon. Yash Chopra went for the romantic in his films like Kabhi Kabhie and Silsila where the poet’s anguish comes from his personal defeats — he is as removed from his world as Hindi films themselves. In one of Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s most intense and darker films, _Namak Haraam_ , we had an alcoholic poet on the peripheries, who dies an agonizing death after suffering the injustices of an exploitative society. Raman Kumar’s Saath Saath had a poet protagonist who first aims to reform the world and make a change. But eventually, we see him conform to the pressures, and become a commercial publisher and pander to the low-brow, leaving all his principles behind. The struggle for women artists is entirely separate. Instead of grappling with grander questions of truth, art, and its place in society, they are left with baser struggle with freedom to be an artist in a world dominated by men, without being punished for it. Do Anjaane, Guide, Bhumika, Abhimaan, Delhi-6, Secret Superstar — the list is endless. Ram Gopal Varma’s Naach was a rare film that showed a female artist fighting with the world to let her be free, both in her life and art. Lajja is another film that portrays the horrific results of a woman trying to make her art political. The artist with a moral compass was more or less a thing of the past now. Violence took over verses entirely. If you see the posters of the biggest films of the early ’90s, eight out of 10 posters have the hero wielding a gun or a weapon. In a post-liberalisation India, perhaps the poet figure was too boring to be charming to the masses after all — and so was eventually replaced by a vigorous stage figure, best exemplified in films like Dil To Pagal Hai and Kaho Na… Pyaar Hai. The 21st century saw a new brand of artists who prefers to keep their art hidden from the world, let alone using it as a political weapon. Siddharth [Akshaye Khanna] in _Dil Chahta Hai_ is a sensitive artist who, however, does not depend on his art for his living. He, in fact, keeps his art a secret, all to himself, making himself vulnerable as an artist only to people he loves and trusts. Jaane Tu… Ya Jaane Na had a similar character in Amit [Prateek Babbar], a complete recluse who makes amazing art on his room walls, but does not even let his family enter his space. The personal might be political, but it still is private because of their privilege — and hence remains non-political after all. We have reached a point where, in _Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara_ , Imraan [Farhan Akhtar], a closeted poet who fronts as a copywriter, is nearly afraid to share his poetry with the closest of people in his life, reflecting an immense inclination to inhibit your true self, the very antithesis of an artist. The contemporary struggle to even pursue your art in a capitalistic society has been the biggest struggle of our protagonists now, reflected in films like Rock On!! and Tamasha. Three films stand out in recent times. Taare Zameen Par had a unique protagonist, an eight-year old with a great flair for painting who literally sees the world differently, owing to dyslexia, and hence remains a misunderstood creature until figuratively rescued by his teacher. Zoya Akhtar’s Gully Boy is essentially an underdog triumph story, the protagonist’s desperate need for expression about his lived experiences lead to him becoming a rap artist and making himself heard. There is yet another telling sequence in Rockstar, where our broken-hearted singer laments about the unjust society that is keeping him apart from his lover in the angsty ‘Saadda Haq,’ which slowly gets co-opted by every listener as an anthem of personal angst. The personal unwittingly becomes political. And yet, perhaps this is the extent to which we can have the depiction of a political artist in current times. The political system has continually undermined the importance of artists in a healthy society, and yet ironically ends up underlining their value by making desperate attempts at arbitrary and fascist-level censorship, which is possibly at its peak today. It is because deep down, we are all afraid of the true power of an artist if they are really let be. Today, Onir is struggling to make a film about a gay Indian Army officer. Last year, the makers of the Amazon Prime Video India Original show Tandav were arm-twisted to make major changes to their content. These are also the times when there are far more discourses around the intersection of art and politics, leading to outcomes of all kinds. The importance of this kind of intersection is brilliantly encapsulated in a sequence in Govind Nihlani’s Party [1984], as a few artists and intellectuals stumble around the topic of the purpose of art and artist. While others stay on the fence between an artist taking a political stand, Avinash [Om Puri] politely rips apart the facade and calls out the hypocrisy, explaining how art is separable from politics, and fails to be relevant if it is not committed to its environment in any way. [caption id=“attachment_10393641” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Waheeda Rahman and Guru Dutt in Pyaasa[/caption] And in these times, Pyaasa becomes all the more a relevant watch, to remind us both of the power and importance of an artist in a politically turbulent environment — in both life and movies. Even though Vijay denounces the present world and leaves with Gulaabo [Waheeda Rahman], it is in the hope of finding a better world to create, to live in. To paraphrase Luis Bunuel, even though they cannot change the world, to keep an essential margin of non-conformity, you will always need an artist. BH Harsh is a film critic who spends most of his time watching movies and making notes, hoping to create, as Peggy Olsen put it, something of lasting value. Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)