(Editor’s Note: This is Part 4 of a series by film critic and consulting editor, Anna M.M. Vetticad)

“Diya jalte hai / phool khilte hai / Badi mushkil se magar duniya mein dost milte hai,” Somu sings with his eyes twinkling and fixed firmly on Vicky’s face. (Lamps burn, flowers bloom, but it is hard to find friends in this world.)

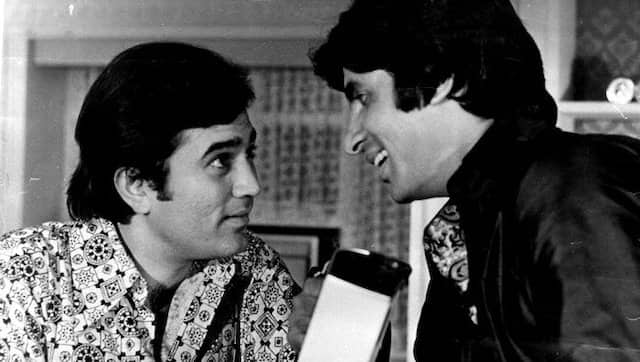

Vicky (Amitabh Bachchan) is filming Somu (Rajesh Khanna) as the song flows from his lips. When he lowers the camera, Somu winks, and still singing with eyes locked on Vicky, wanders over to a table to pick up food that he feeds his friend.

“Jab jis waqt kisi ka / yaar judaa hota hai / kuchh na poochho yaaron dil ka haal bura hota hai,” he continues. (Whenever one is separated from a friend, don’t ask about the terrible state of the heart.)

“Dil pe yaadon ke, jaise teer chalte hai.” (The memories strike the heart like arrows.)

Serious students of Hindi cinema would immediately recognise this scene. Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Namak Haraam (1973) is, after all, iconic. Among other things, it is a watershed in both Khanna and Bachchan’s careers. For Khanna, the reigning superstar of the time, it marked the beginning of the end since it showcased to his disadvantage his screen presence versus Bachchan’s searing charisma in a year in which Prakash Mehra’s Zanjeer had already signalled his arrival as a box-office phenomenon.

When I first watched Namak Haraam as a little girl in the 1980s, I knew none of this. Historians tend to record the beloved classic in these terms, and as a buddy flick about class conflict against a backdrop of the mill workers’ unions in 1970s Mumbai. The description is apt, but what branded the film on to my brain in my childhood was the possibility of an individual rising above his upbringing, conditioning and apathy to develop empathy for a people he once ignored. The seeds of thoughts Namak Haraam planted in my young head are the reason why it is on my list of films that set me thinking about cinema in ways that ultimately led me to my profession.

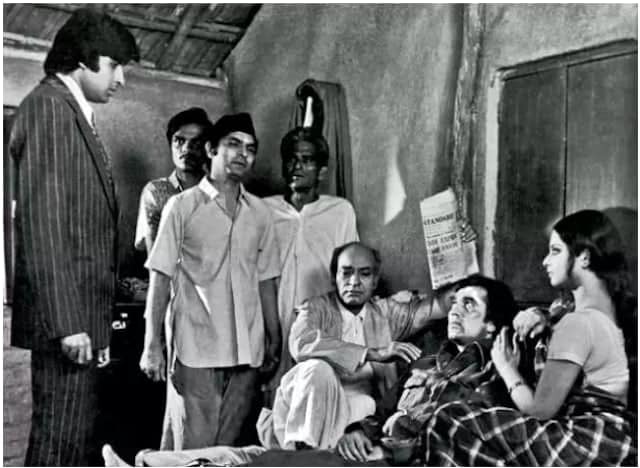

Somu in Namak Haraam lives with his widowed mother (Durga Khote) – a staple of 1970s cinema – and unmarried sister. Vicky steers clear of his millionaire father’s business. Somu’s lower middle class family is of limited means and Vicky finances the day-to-day running of their home.

The closeness of their bond is indicated by scenes in which they wear identical shirts, get jobs at the same firm, drink together, visit nautch girls and misbehave with their other patrons. That is, until circumstances force Vicky to work for his father. The turning point of the plot comes when the tempestuous Vicky insults the workers’ union chief Bipin Lal Pandey (A.K. Hangal), and his Dad advises him to apologise to the man with a long-term divide-and-rule strategy in mind.

Unable to bear Vicky’s humiliation and tears, Somu goes undercover as a worker to win his colleagues’ trust and defeat Bipin Lal in the next union elections. However, when he witnesses the workers’ poverty and problems up close, he finds himself unable to return to his previous life and becomes a genuine advocate of their rights. In Vicky’s eyes, Somu thus becomes a namak haraam (traitor).

[caption id=“attachment_8884591” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Rajesh Khanna and Amitabh Bachchan in Namak Haraam.[/caption]

Of all the films I have included in this series, Namak Haraam is the most flawed. For one, Somu and Vicky’s initial leeriness is given indulgent treatment by the director. Women have a token presence in the narrative in formulaic roles: dependent mother, dependent sister, nautch girl, love interest. Rekha plays the latter, a fussy creature whose relationship with Somu kicks off with a silly, contrived clash, the sort that was deemed mandatory at one time to spark off any man-woman romance in a Hindi film.

Simi Garewal’s character at least got to have thoughts that went beyond her attraction towards a man: Nisha is the woman that Vicky’s Dad is trying to set him up with; Vicky sneers at her socialist values that he considers oxymoronic since she is a crorepati’s daughter, but she is unwavering in her convictions – however, she never gets to elaborate on her position and has barely any screen time.

Mukherjee was a stalwart of middle-of-the-road Hindi cinema. That he had the workers’ welfare at heart in Namak Haraam is not in question, but the middle path he walked between larger-than-life commercial cinema and the stark realism of what was categorised as art cinema meant that the concerns of the poor were shown here to an extent that, while possibly making middle class and wealthy viewers uncomfortable, avoided the depth that could turn their discomfort into animosity.

Towards this end perhaps, Namak Haraam does not discuss caste. And a question Vicky asks Bipin Lal while refusing to pay compensation to a worker injured in his factory – “did I stick his hand into that machine?” – is never fully addressed. Instead, monetary reparation for work-related accidents is positioned as a gesture the rich should extend to the poor out of a sense of “duty” (Bipin Lal’s choice of words), and the culpability of owners for faulty work conditions is never examined.

Of course this does not mean that Namak Haraam should be brushed aside. It is a powerful film that served its intended purpose, using an entertaining format complete with song and dance to highlight two issues for a mass audience: economic conditions that make it impossible for hard-working blue-collar job holders to live with dignity and the government’s responsibility to keep businesses in check.

Vicky’s father’s suspicion of the middle class also offers a wonderful insight into real-life class divides and is a sample of fabulous writing (credits: story – Mukherjee, screenplay – Gulzar and D.N. Mukherjee, dialogues – Gulzar). The middle class are a dangerous and untrustworthy lot, he explains, driven as they are on the one hand by aspiration, thus making them prone to betrayal, but on the other hand, by their conscience, thus making them prone to turning against the rich at any moment.

Through all this, Namak Haraam’s fulcrum remains Vicky and Somu’s friendship.

In a 2014 article I wrote on the history of LGBT+ portrayals in Bollywood, Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai, co-editors of the book Same-Sex Love In India, cited the yaari-dosti films of that era as examples of coded messaging aimed at closeted members of the community and designed for a conservative audience that would not openly acknowledge their existence. Films that have come up in my discussions on the subject with several academics, activists and contemporary filmmakers over the years include Dosti (1964), Sangam (1964) with Raj Kapoor and Rajendra Kumar, Anand (1971) and Namak Haraam (1973), both starring Khanna and Bachchan, and Sholay (1975) with Bachchan-Dharmendra.

Vanita said: “I’ve shown these films to my students here (at the University of Montana, the US), and all of them commented on the fact that the men are singing romantic songs to each other like Diye jalte hai and the songs from Dosti. If you played those songs without knowing that a man is singing to a man, it sounds like a man is singing to a woman. The way they look into each other’s eyes while singing, put food into each other’s mouths, all these gestures have meaning within the economy of cinema. My students say, and I agree, that in Hollywood you have the buddy movie but buddies don’t behave in this intense romantic way.”

[caption id=“attachment_8884641” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  A still from Namak Haraam.[/caption]

The intensity of the male bonding in those old-time yaari-dosti films could be attributed to multiple factors. First is Hindi cinema’s penchant for over-statement combined with its inclination from the 1970s Bachchan era onwards to marginalise women and centralise men in every way possible. The homo-erotic undertones of these films cannot be ignored though, and it is just as likely that writers and directors of the time were quietly reaching out to gay men in the audience through unstated elements in their storylines. I have sometimes wondered, however, whether this view of such films does not also indicate a different form of conservatism: an inability to view any close relationship outside the lens of romance. An indicator of Mukherjee’s intent comes from watching British director Peter Glenville’s 1964 film Becket that inspired Namak Haraam.

Becket is a fictionalised, factually inaccurate account of the relationship between two historical figures from 12th century Europe: King Henry II of England (played by Peter O’Toole) and his close friend turned foe, Thomas Becket (Richard Burton). Using his powers as the monarch, Henry names Becket the Archbishop of Canterbury in a bid to tighten his control over the Catholic Church. Becket had until then been unswervingly loyal to Henry, despite being one among the people conquered and oppressed by Henry’s dynasty. The moment he gets his new title though, he starts acting solely in the interests of the Church, thus leading to a bitter rivalry between the two men.

In terms of its main plotline, Becket is far removed from Namak Haraam. Until they split, for instance, Henry is shown to be extremely condescending towards Becket despite his fondness for him; this is unlike Vicky who does not display an iota of condescension towards Somu. Besides, Becket is well aware of the dishonour in his indifference to his own community. Somu is oblivious to the harshness of class inequity, and frankly, his ignorance reflects the contemporary discourse about such matters among upper-caste urban Indians who, firstly, equate caste with class, and second, insist that “there is no caste system any more, at least among people like us”.

That said, Somu’s change of heart is a believable, gradual transition that results from exposure to a less privileged people, whereas Becket’s transformation is abrupt and comes from an inexplicably sudden devotion to God and the Church.

The telling parallel between Namak Haraam and Becket though comes from the personal equation between them.

In Namak Haraam, Vicky and Somu’s emotions are a constant but never publicly expressed with a passion implying anything more than fealty to a friend and thus are never viewed with suspicion by a homophobic society. In Somu’s case there is a perfunctory romance with Rekha’s Shama and some teasing, but he never looks at her with the warmth he reserves for Vicky.

In Becket though, the extent of Henry’s feelings for Thomas is revealed only after they fall out, there is a possibility that his love is unrequited, and the end of their friendship leads Henry – married and a father – to unravel in the presence of his courtiers, his family and the help, raging on and on about his love for Becket. Though a romantic interest is not clearly declared, during one particular rant his mother admonishes him for what she calls his “unhealthy obsession” with Becket. Later, almost wilting under a combination of rage, heartbreak and a bruised ego, Henry breaks down before a handful of courtiers, admitting that he loves Becket, shedding tears as he tells them that he is “as useless as a woman. So long as he (Becket) is alive, I tremble, I shake”.

Though Henry in 12th century Europe could not explicitly articulate the A-Z of his sentiments, he could, within his royal circle, afford such an outlet, and a late 20th century Western film could afford to be more overt in its portrayal of Henry and Becket than Namak Haraam could be in 1970s India, where even the whisper of such a truth could destroy a man. Considering the nature of film censorship in India, the violent tendencies of conservative political parties and social hypocrisy, the likes of Mukherjee might have deemed it safest to have his hero gazing at his male friend and singing of memories striking at the heart like arrows while having nominal girlfriends on the periphery of the narrative.

Either that, or this is an over-reading of Namak Haraam. That’s the thing about great cinema, of course: you can never stop thinking about it or trying to peel off the layers. Namak Haraam, intriguing, gripping and moving as it is, with its likeable cast, towering performances by Bachchan and Om Shivpuri (as Vicky’s father), an excellent soundtrack by R.D. Burman and lyrics by Anand Bakshi, is one of Mukherjee’s finest.

ALSO READ:

- Indian films that sparked the critic in me: Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar is the definitive feminist classic

- Indian films that sparked the critic in me: Ramu Kariat’s Chemmeen remains misunderstood and misrepresented – even by its admirers

- Indian films that sparked the critic in me: Jahnu Barua’s Hkhagoroloi Bohu Door is an indictment of cold-hearted development

- Indian films that sparked the critic in me: Rituparno Ghosh’s Dahan is every woman’s story

- Indian films that sparked the critic in me: Fazil’s Manjil Virinja Pookkal owes everything to Jerry Amaldev’s music and Mohanlal

- Indian films that sparked the critic in me: Jwngdao Bodosa’s Hagramayao Jinahari is a rare window into Bodo life

- Indian films that sparked the critic in me: Abrar Alvi’s Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam embodies sensuousness and self-destructive decadence

- Indian films that sparked the critic in me: Aparna Sen’s 36 Chowringhee Lane is the ultimate portrait of rejection in old age

- Indian films that sparked the critic in me: Singeetam Srinivasa Rao’s Pushpaka Vimana speaks volumes with its silence

- Indian films that sparked the critic in me: Raj Kapoor's Awara swings between feminism and romanticising intimate-partner violence

- Indian films that sparked the critic in me: P. Bhaskaran & Ramu Kariat’s Neelakuyil married caste, sexual politics and George Eliot

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)