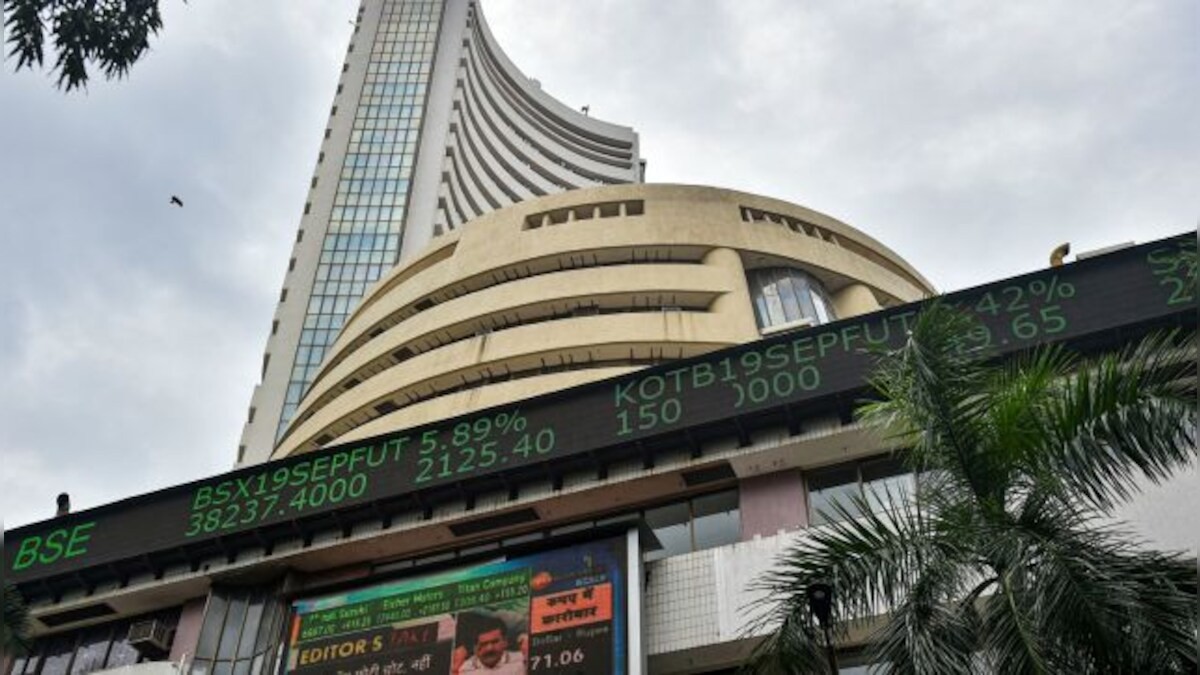

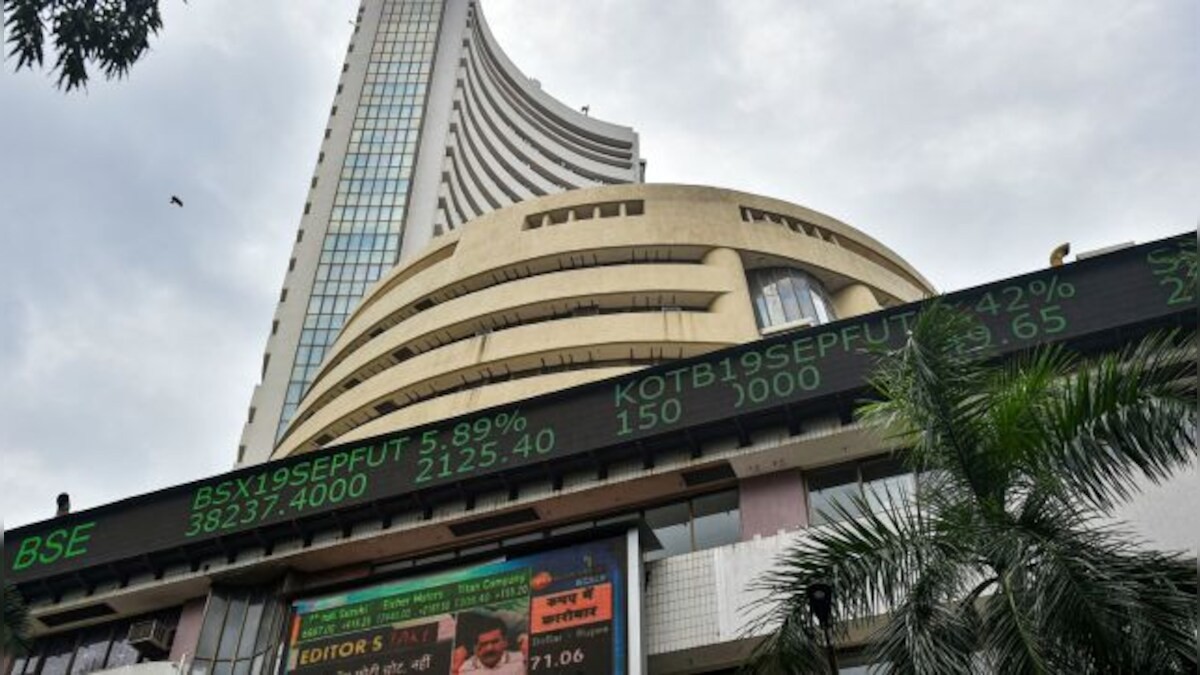

Before we decide whether the National Stock Exchange of India Ltd (NSE) should list, it is important to understand the nature of the beast, the underlying asset.

The business of India’s largest exchange, formed two decades ago, is unlike any of the companies that list on it, barring banks. In all other companies, the profits and losses are limited to one firm, its clients and shareholders.

But NSE, like the Bombay Stock Exchange, provides a critical financial market infrastructure and the business needs to be seen from two sides — profits and compliance. The critical differentiator here is regulatory oversight the company has been outsourced and entrusted with. Any compromise here would reflect not only on NSE but on all the 1,600-plus companies listed on it.<

Global private equity investors including SAIF Partners, Actis, General Atlantic, IDFC, NVP, Tiger Global, Temasek Holdings, and Beacon India that hold a 28 per cent stake in NSE are reportedly unhappy that the exchange is refusing to either list or pay higher dividend.

This, they say, goes against the collective interest of its shareholders. They are seeking an exit from NSE by getting the company to list. What they need to understand - and probably do - is the potential conflicts of interest that can arise out of taking NSE public.

On the other side, not all NSE investors are seeking a listing. The two largest shareholders, Life Insurance Corporation, and IDBI Bank that hold a 15.5 per cent stake in the exchange, are comfortable staying unlisted. “The question of listing does not arise at all,” an LIC executive told The Economic Times . Of course, the fact that these are public sector entities helps shape this outlook.

Investing in companies that run critical financial infrastructure, such as stock exchanges, credit rating agencies, clearing corporations and depositories, carries a risk of public policy. Any large investor should know that when the government outsources its first line of regulatory and supervisory functions to a private firm like the NSE, the responsibility to serve that function goes more than mere compliance. A compromise here would impact not just one entity and its shareholders; it affects thousands of companies, millions of investors.

The potential risk of abusing this regulatory and supervisory function in the quest for profit becomes higher when such a company gets listed. This higher risk comes in two ways.

A listed firm’s returns to investors is more than mere increased profits — a Re 1 of net profit translates into Rs 20 in the value of the firm that would trade at a PE multiple of 20. So, the pressure from investors can hang like a golden sword on the heads of managers.

Second, if managers themselves become participants in those returns through stock options, the high-powered incentives have the potential to bite regulatory requirements twice over.

There are many ways an exchange can compromise its regulatory function. The market value of a valuation-focussed exchange rises with increased turnover, so encouraging fake circular transactions would help raise valuation. Or a large securities firm with malpractice at heart could go regulatory shopping and threaten to shift to another exchange if enforcement is too strong. Or conversely, if a firm is diverting business to a rival exchange, it could harass the firm through inspections. And so on.

One way out would be to segregate the regulatory functions of an exchange from the profits it makes. This can be done by hiving off the regulatory arm and turning it into a not-for-profit organisation, an SRO (self-regulatory organisation) for instance, with clear regulatory compliance expectations from its management.

Perhaps an SRO formed by association of exchanges with regulatory oversight by Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) might work. The problem here is that, from the Medical Council of India to the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India, the state of SROs in India leaves a lot to be desired.

The other way would be to transfer the regulatory function back to the government or regulator SEBI. But that would turn the entire structure of outsourcing the regulatory work to a private firm on its head. Given the rather weak governance capacity, dealing with a single entity would be a better option for SEBI to deliver regulatory compliance.

The process of listing stock exchanges began with their demutualisation, a process that transformed them into profit-making, investor-driven corporations from non-profits, members-owned organisations — Stockholm Stock Exchange in 1993, Helsinki Stock Exchange in 1995, Copenhagen Exchange in 1996, Amsterdam Exchange in 1997, Australian Exchange in 1998 and Toronto, Hong Kong and London exchanges in 2000. Following the securities scam of mid-1990s, the Bombay Stock Exchange was formally demutualised in 2007, while NSE, created in 1993, was born demutualised.

Listings followed — Australia in 1998, Hong Kong in 2000, London in 2001, New York in 2006, and Moscow earlier this year. But applying the demutualisation trend to listing may neither be in so straight a line, nor so easy to accomplish. While SEBI has allowed bourses to go public with their shares on exchanges other than themselves through a June 2012 notification , the reporting line of the compliance officer to the board of the exchange may not be such a great idea.

Further, even if the oversight committees are chaired by public interest directors, their efficacy and effectiveness when functioning within the same corporate structure as the rest of the organisation is unproven.The regulatory function - a clear public good that needs public scrutiny and control - needs to be completely isolated from the profit-generating part of the exchange.

I believe SEBI needs to do some more work on this front. Until then, NSE should not list. Threats or noises made by some of its investors seeking an exit can’t overrule market safety and regulatory sanctity. Only once this potential conflict of interest is resolved and we are assured that the regulatory compliance is in safe hands, should the NSE board give these voices of listing a hearing.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)