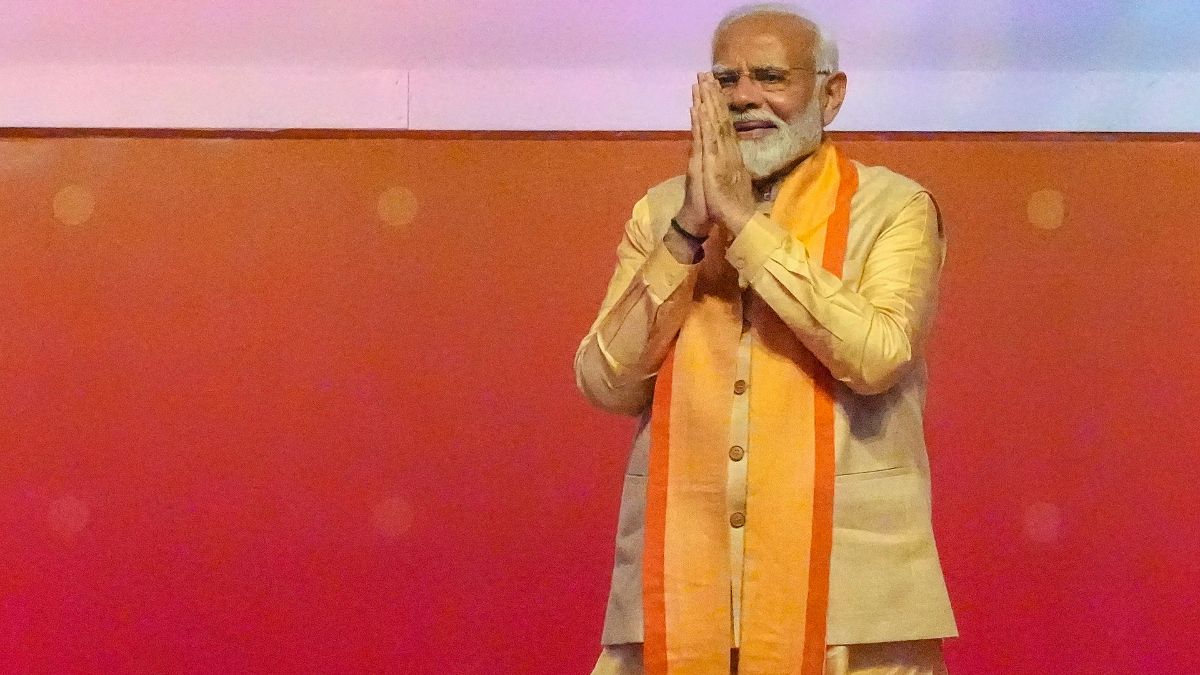

One of the frequently heard key words Prime Minister Narendra Modi has used during his mega foreign trips is the NDA government’s ambitious ‘Make in India’ plan.

Modi wants to change India, and rightly so, as the world’s export hub primarily pinning hopes on the country’s manufacturing sector and Make in India drive. The country has set an ambitious $900 billion export target by 2020. But, the reality might be far different. India’s export sector is facing a serious problem – something that can potentially hurt Modi’s big dream.

India’s exports have fallen for the 12th consecutive month in November by more than a quarter to $20 billion, which exporters describe as a worse situation than the 2008-09 global financial crisis period. According to rating agency, Crisil, the local subsidiary of Standard & Poor’s, India’s trade (exports plus imports) to GDP ratio has fallen drastically from 55.6 perpcent at peak in fiscal 2013 to 46 percent in the second quarter of the current fiscal.

“The decline of such magnitude is the first since the start of economic liberalisation in 1991,” it said. While the slowdown in both exports and imports has contributed to this trend, the greater worry is the decline in exports, the agency notes. Imports too have fallen in November by a sharp 30 percent, led by a 63 percent decline in fertiliser imports, and a 45 percent dip in oil imports. This is a reason why there isn’t much impact on the trade deficit.

But the critical point here is that the slowdown in imports is largely temporary and the drastic slowdown in exports can be lasting. This is more worrying.

“While imports would rise as domestic demand and investments pick up and commodity prices stabilize, exports are likely to remain weak because of subdued global growth – especially when there is structural weakness in trade,” Crisil said.

Federation of Indian Export Organizations estimate this year’s (2015-16) exports to be in the range of $260-$270 billion, whereas in 2014-15, the country’s total exports stood at $470 billion in value terms. India’s merchandise exports, which are almost two-thirds of India’s total exports, have been declining in the last 12 months. Cumulatively, they have fallen 18.5 percent in dollar terms in the first eight months of this fiscal, after seeing a 1.5 percent decline in fiscal 2015.

It is logical that in a slowing world, exporting countries will take a hit as the global demand is low. As it appears now, the slowdown that has gripped the major global markets is a prolonged one in nature. This is true for Europe, the Middle East (hurt by plunging oil prices) and even the US, where there is a nascent recovery.

So here are the questions: Will it be still prudent to pin our hopes on exports alone for Modi’s big manufacturing push? When the world slows and the global demand is weakening, whom should India make for? This question is something Crisil points out very emphatically. “This (export slowdown) casts a shadow on the government’s flagship ‘Make in India’ programme, which aims to generate large-scale manufacturing employment and make India a world-class exports hub,” Crisil said.

The answer, perhaps, lies in tapping the domestic market more aggressively, rather than solely relying on an export-led model.

Rajan’s warnings

In fact, Raghuram Rajan, the government’s former economic advisor and the current governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), had made a case against Modi’s export-dependent model long back, citing global demand slowdown. In December last year, Rajan said, “There is a danger when we discuss “Make in India” of assuming it means a focus on manufacturing, an attempt to follow the export-led growth path that China followed."

In hindsight, Rajan’s advice proves to make more sense in the evolving global scenario. Not just the export factor, Rajan also questioned the over-dependence on the manufacturing sector. “I am… cautioning against picking a particular sector such as manufacturing for encouragement, simply because it has worked well for China. India is different, and developing at a different time, and we should be agnostic about what will work," Rajan had said.

But was Rajan being overly pessimistic on India’s export picture. Not really. His views were more realistic foreseeing the likely prolonged slowdown phase in the economy.

India needs to look to “regional and domestic demand for our growth - to make in India primarily for India, Rajan said. “If external demand growth is likely to be muted, we have to produce for the internal market. This means we have to work on creating the strongest sustainable unified market we can, which requires a reduction in the transactions costs of buying and selling throughout the country.

The problem can be tackled by creating an environment, where all sorts of enterprise can flourish, and then leaving entrepreneurs, of whom we have plenty, to choose what they want to do, not necessarily the manufacturing segment alone, Rajan said. His advise deserves merit in the current context of India’s export problem.

It is unlikely that exports will see any major revival in the foreseeable future, especially in the context of fresh warnings coming from economists like Larry Summers about the possibility of another recession and fresh tensions emerging in the middle-east. The current phase of export slowdown perhaps offers a good reason for the Modi government to rethink on its strategy on Make in India.

(Data support from Kishor Kadam)

)

)

)

)

)