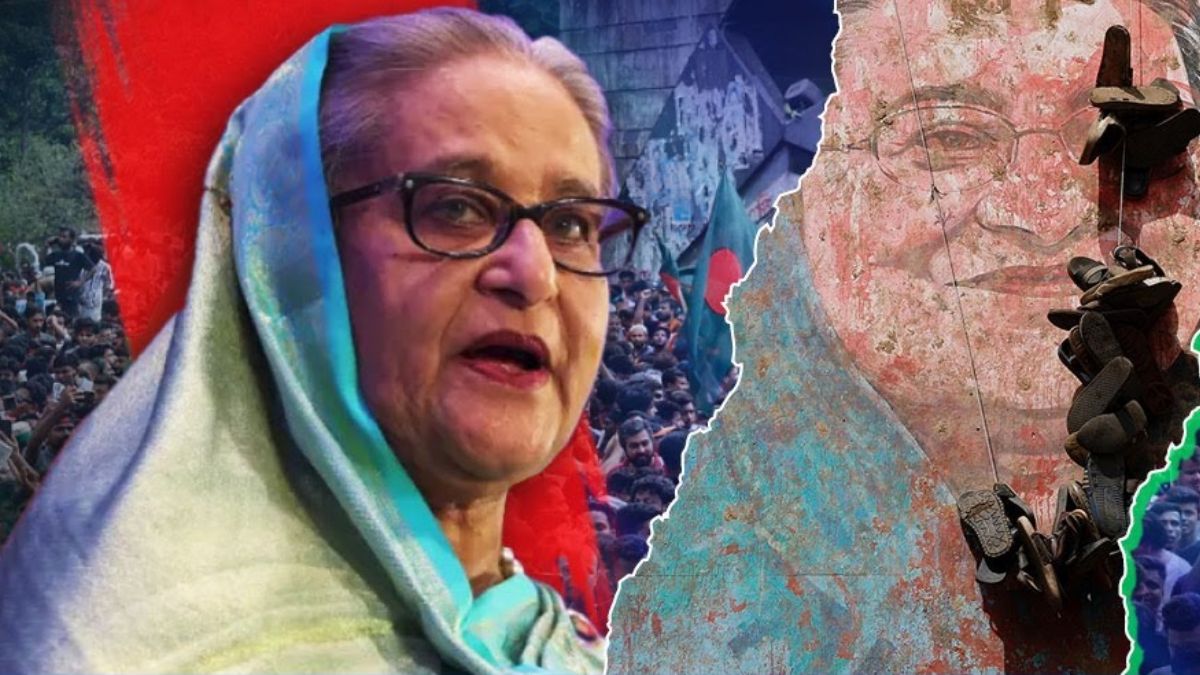

On November 17, Bangladesh’s International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) sentenced the country’s former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to death in absentia over charges of crimes against humanity during the July 2024 protests. This was the first time in the country’s history that a former prime minister received a death sentence, leaving many divided on the verdict.

While some emphasised the plight of the victims of the violent protests that toppled the Hasina government, others raised human rights concerns, calling out the court’s tendency to award capital punishment. Many also pointed to the irony of the whole saga, given the fact that it was Hasina who established the court in the first place, and it was her father, Bangabandhu Mujibur Rahman, who laid the foundation for the tribunal.

The court was established to provide retributive justice to victims of atrocities committed during Bangladesh’s 1971 liberation war . For years, ICT remained one of Hasina’s most powerful judicial instruments – a court she created, expanded and heavily defended. Ultimately, it was the same court, which underwent a reconstruction after she was ousted, that ended up giving her a death sentence.

In an email interview with Firstpost, Toby Cadman, special adviser to ICT’s chief prosecutor and an expert in international crime and human rights law, shared his take on Hasina’s verdict. Interestingly, Cadman was one of the prominent critics of the ICT process when Hasina was in power.

He not only represented and advised defendants tried in the court, but was also banned from entering Bangladesh in 2011 after he questioned the transparency of the tribunal. In the interview, he also threw light on what changed.

On Hasina’s trial and verdict

When asked about his overall assessment of the verdict in the Hasina trials, Cadman emphasised that Bangladesh’s former PM was afforded “every opportunity to appear before the tribunal”, that she played a key role in establishing. “Her decision not to participate and not return to stand trial was a matter of personal choice, not a result of any procedural unfairness or lack of opportunity,” Cadman told Firstpost.

Hasina has maintained that she was denied the opportunity to have lawyers of her choice to defend her in the ICT. The state appointed her defence lawyer. However, Cadman maintained that procedure remained transparent.

Quick Reads

View All“She was afforded state-appointed counsel in accordance with the legal framework that her government had implemented. She did not nominate lawyers to appear on her behalf or seek to engage with the proceedings,” he said.

While Cadman defended the verdict and pointed to Hasina’s decision not to appear for the trials, it became important to point out the circumstances in which Hasina fled the country. Right after she left Dhaka, violent protesters barged into her residence and even vandalised buildings made to honour her father. Workers from the Awami League and even Hasina herself maintained that there was a significant risk to her life during the protests. Hence, Hasina’s security would have been a concerning factor during the trials.

On allegations of bias and political vendetta

Since the start of the trial, Hasina and her supporters often described the ICT as “Kangaroo court” and insisted that the trial was a “political vendetta” against the former Bangladeshi premier. In the interview, Cadman defended the institution, which he played a crucial role in restructuring after the Hasina era. “Sheikh Hasina has chosen to criticise the process rather than engage. As the special adviser to the prosecutor, I must address the allegations of bias and political vendetta with the utmost seriousness. The integrity of the tribunal and its proceedings is paramount, and every effort must be made to ensure that justice is served,” he said.

“The legal process was anchored in both domestic legislation and established international standards, with particular attention paid to safeguarding the rights of the accused. Significant changes were made to the legal process to safeguard the rights of the accused.”

Cadman went on to recall the trials under Hasina’s rule, pointing to the “political interference at every level”. “Sheikh Hasina is clearly conflating the judiciary under her tenure with the trial process now. Claims of partiality, in my view, often overlook the substantial evidentiary basis underpinning the conviction, and conflate legitimate judicial action with political motivation,” he asserted.

“It is important to recognise that the tribunal was constituted with procedural safeguards under a legal framework that Sheikh Hasina’s government implemented, and was subject to both domestic and international scrutiny at each stage. While criticism is inevitable in high-profile cases of this nature, the prosecution’s mandate was to pursue justice in accordance with the law, not to serve any political agenda. Ultimately, the focus must remain on the rule of law and the pursuit of accountability, rather than on unfounded allegations that risk undermining public confidence in the judicial process,” he said.

Regional & political implications

Impact on Bangladesh’s domestic political stability

When asked about the implications of the Hasina verdict, Cadman acknowledged that the former premier’s conviction will have a profound impact on Bangladesh’s political landscape. “Such a judgment inevitably exerts pressure on Bangladesh’s internal stability and governance. High-profile convictions can serve as catalysts for polarisation, potentially fuelling unrest among political factions and testing the resilience of democratic institutions. That said, the commitment to due process is intended to reinforce, not undermine, public trust in the system,” he said.

“Critics may argue that the conviction risks exacerbating divisions within Bangladeshi society, but it is imperative to differentiate between legitimate judicial accountability and political manoeuvring. The prosecution’s role was not to advance a political agenda, but rather to uphold the principles of justice and accountability.”

“In the long term, the integrity of the proceedings should serve to strengthen governance, provided that all parties respect the outcome and engage constructively with the country’s legal institutions. The true test for Bangladesh will be its ability to navigate these turbulent times by prioritising the rule of law and democratic values over partisan interests,” he furthered.

It is pertinent to note that Hasina’s verdict triggered an unprecedented unrest across Bangladesh, with the Awami League calling it an “unfair trial”. Since the tribunal’s verdict announcement on November 17, the Awami League has mobilised supporters in mass protests, shutdowns, and street demonstrations, calling for the resignation of the interim government and the reversal of the sentence.

The party condemned Yunus as a “usurper” and “killer-fascist,” accusing him of manipulating the tribunal to eliminate political rivals ahead of the scheduled general elections in February 2026. After Hasina was ousted, her party was banned from contesting the polls, a decision many termed as “undemocratic”.

The country remains divided

Cadman admitted that public opinion over the verdict remained divided. “For many, the verdict is perceived as a necessary assertion of judicial independence and a reaffirmation of the rule of law. These individuals point to the transparent nature of the proceedings and the robust evidentiary basis for the conviction as evidence that justice has been served, irrespective of the defendant’s political stature,” he said.

However, the UK-based barrister also acknowledged the views on the other side of the aisle. “Conversely, a portion of the public, namely Sheikh Hasina’s political allies and supporters, view the conviction through a lens of scepticism and mistrust. For these critics, the legal process is inseparable from the prevailing political climate, and they question whether the proceedings were truly free from external influence or political motivation,” he exclaimed.

Cadman maintained that the criticism is fueled by “Bangladesh’s history of contentious legal actions against high-profile figures, leading to fears that the verdict could be exploited as a tool for consolidating power or marginalising dissent.”

“The polarised responses reveal a society grappling with issues of legitimacy, accountability, and trust in public institutions. The strength of these divergent reactions underscores the urgent need for continued vigilance in safeguarding judicial independence and promoting open, good-faith dialogue across the political spectrum. Only through such measures can Bangladesh hope to bridge its divisions and foster a more inclusive, resilient democracy in the face of ongoing challenges,” he averred.

Regional implications

During her time in office, Hasina maintained strong ties with two key regional players of Asia: India and China. Cadman admitted that the trial will have significant regional implications as well.

“It is essential to approach the potential regional ramifications of Sheikh Hasina’s conviction with both caution and clarity. The tribunal’s decision, while grounded in the law, will undoubtedly be scrutinised by Bangladesh’s neighbours, particularly India and China. Both countries have vested strategic and economic interests in the stability of Bangladesh, and any perception of judicial overreach or political manipulation could complicate diplomatic relations,” he said.

However, he reiterated that the ICT acted independently of international pressure. Cadman went on to urge India to extradite Hasina, citing the extradition treaty signed by the two nations. “India has an obligation to properly consider her extradition in accordance with the treaty, something they have failed to do so far,” he said.

After Hasina’s conviction, India maintained that it is committed to the best interests of the people of the neighbouring country. In a statement, the Ministry of External Affairs noted, “India has noted the verdict announced by the ICT concerning former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina.

“As a close neighbour, India remains committed to the best interests of the people of Bangladesh, including peace, democracy, inclusion and stability in that country. We will always engage constructively with all stakeholders to that end,” it added.

Since Bangladesh has formally issued an extradition request after Hasina’s verdict, India will now have to assess the ruling against its obligations under the 2013 agreement signed by then-Home Minister Sushil Kumar Shinde during a visit to Dhaka.

However, the 2013 extradition has several exceptions the government could use to defend its grant of refuge to Hasina. One such exception is enshrined in Article 6 of the treaty that stipulates that extradition may be refused if the offence is of a “political nature”. Hence, Hasina’s extradition, especially after a death sentence, remains a complicated issue.

Addressing the human rights concerns: Court’s tendency to award capital punishment

For decades, the ICT has been criticised by human rights groups from around the world for awarding capital punishments. Cadman himself has criticised the process the tribunal was operating in the past. When asked about these concerns, the newly appointed advisor to the chief prosecutors acknowledged these issues.

“I am acutely aware of the gravity of the concerns raised from a human rights and rule of law perspective, particularly given the historical criticisms levelled at the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) regarding the imposition of capital punishment and the practice of trying individuals in absentia under Sheikh Hasina’s government,” he told Firstpost.

“It is both necessary and proper to acknowledge that no judicial process is above scrutiny, and that robust debate about the fairness and proportionality of such measures is vital to the ongoing legitimacy of any legal institution,” he added.

However, Cadman separated the nature of trials conducted under the Hasina government from how ICT operated in this case. “The trials under Sheikh Hasina’s government were termed as a flagrant denial of justice, including evidence-based, credible allegations of political interference, prosecutorial and judicial misconduct, and the circumvention of the rule of law,” he said.

“Let us not forget that Sheikh Hasina herself said publicly after one unfavourable decision by the ICT during her tenure that resulted in public demonstrations demanding the death penalty, that she would speak to the judges and make them understand the sentiment of the people. That resulted in the judges overturning a sentence of life imprisonment and imposing a sentence of death, which was subsequently carried out. Clearly, Sheikh Hasina and her political supporters are conflating the current tribunal with its own conduct of political interference. One should not confuse the two.”

“Yes, there may be criticisms to be made of the process, but any criticisms, real or not, pale in comparison to the trials conducted under her tenure,” he added.

While Cadman is defending Hasina’s conviction, several international bodies called out ICT for handing down a death sentence to the country’s former PM. The United Nations has said that the verdict against Bangladesh’s ousted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina on charges of crimes against humanity is an “important moment” for the victims, but expressed regret over the imposition of the death penalty.

“UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres fully agreed with UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Turk on the position that we stand against the use of the death penalty in all circumstances,” the UN chief’s spokesperson Stephane Dujarric said at the daily press briefing, a day after the verdict.

Meanwhile, Amnesty International also condemned Hasina’s death sentence. Amnesty International Secretary General Agnès Callamard said in a statement that “the ruling represents a grave miscarriage of justice, warning that the verdict fails to deliver accountability for the victims of last year’s violence and instead risks deepening Bangladesh’s human rights crisis.”

The body noted that the verdict raises significant fair trial concerns, citing the tribunal’s long-criticised lack of independence and history of politically influenced proceedings. The organisation noted that the trial was “conducted at unprecedented speed, despite the scale and complexity of the case, and highlighted multiple due-process failures.”

What lies ahead for Hasina

When asked if there is any scope for reversal of the sentence awarded to Hasina and her top aide, Cadman maintained that Hasina will have to engage with the Bangladesh judicial system. “There is a functional judicial system, independent of politics, and a legal framework that allows for appeals should Sheikh Hasina choose to engage rather than merely criticise from her self-imposed exile in India. That is a matter for her. Regardless of what decision she ultimately takes, the decision convicting her stands,” he said.

In her five-page response to the verdict , Hasina said that the charges should be brought before the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague. In March, Cadman also suggested that the July protests should be referred to the ICC.

However, in the Firstpost interview, Cadman emphasised why conducting the trial in the domestic institution was important. “I must emphasise that Sheikh Hasina’s criticisms regarding the verdict and her call for the charges to be brought before the International Criminal Court (ICC) are largely political in nature and lack substantive legal merit. Her assertions appear to be designed to shift the narrative away from the judicial findings and to cast aspersions on the integrity of Bangladesh’s legal system, rather than engaging meaningfully with the evidence or the judicial process itself,” he said.

“It is true that I advocated for the ‘Situation in Bangladesh’ to be referred to the ICC. That was, of course, a matter for the Interim Government to determine. It was considered appropriate to try the cases domestically; I respected that decision. It is crucial that trials for serious crimes are conducted in the locality where the offences occurred, as this ensures that victims and affected communities have genuine access to the judicial process.”

“The suggestion that the July protest cases—or indeed the charges against her—should be referred to the ICC disregards the principle of complementarity, whereby international courts intervene only when domestic avenues have demonstrably failed to deliver justice. Thus far, there is no credible basis to suggest that Bangladesh’s judiciary is either unwilling or unable to adjudicate these matters independently and fairly,” Cadman furthered.

What lies ahead for Bangladesh?

When it comes to the possible scenarios for Bangladesh’s political future in light of these recent events, Cadman maintained an optimistic stance on the matter. “I see the future as bright. There will be elections next year that will be free and fair – something that was not seen under the previous government. The conviction of Sheikh Hasina marks a pivotal juncture in Bangladesh’s political trajectory, inviting both domestic and international scrutiny,” he told Firstpost.

“The immediate aftermath reveals a society wrestling with entrenched divisions, where the verdict has become a lightning rod for debates about the integrity of public institutions and the health of the nation’s democracy. While some view the conviction as a testament to judicial independence and the rule of law, others, Sheikh Hasina’s supporters, have sought to undermine the process by advancing allegations that political considerations may have influenced the outcome.”

He noted that Bangladesh is at a crossroads after the recent events. “The conviction could either serve as a catalyst for greater meaningful reform—driving greater accountability and strengthening democratic institutions—or exacerbate existing tensions, leading to further instability. Ultimately, Bangladesh’s future will depend on its future leaders’ willingness to foster open dialogue, uphold human rights, and pursue justice without fear or favour,” he said.

Why the change in stance

When asked about why his stance on ICT changed over the years, Cadman once again emphasised that ICT under Hasina was different from the ICT of today. “From my perspective as special adviser to the prosecutor and as someone who previously represented a number of accused during 2010-2014, my concerns regarding the operation of the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) have been longstanding and well-documented,” he averred.

Toby Cadman is also the co-founder of Guernica37 Law Chambers, a firm specialising in international law. He has worked on cases in Bosnia, Kosovo, Rwanda, Yemen, Syria, and Ukraine.

)