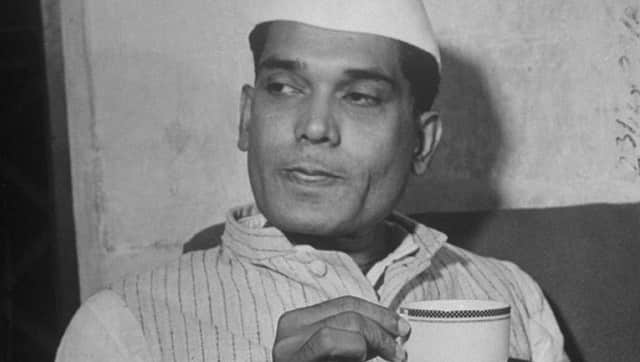

Lalu Prasad Yadav represents a breed of political patriarchs fast getting snuffed out. He has had some sky-scraping highs, colossal lows, and a few redemption songs. But Lalu Prasad was a marquee name that became mud, like none other. A cultivated charm, rustic humour, quirkiness, quick at repartee all added to his universal appeal. Tufts of hair protruding from his ear were a cartoonist’s delight. The backstory was a writer’s delight. He came from nowhere and transformed himself into a giant killer. Commanding political respect across the spectrum, he created his own niche vote bank and never blinked in the face of trouble. Today, elections come and go, controversial issues crop up and die down but there is not a squeak now out of Lalu. His continuing entanglement with the law and resultant irrelevance is a cautionary tale. The Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) chief and former Bihar chief minister has been found guilty of illegal withdrawals of Rs 139.35 crore from the Doranda treasury by a special CBI court in Jharkhand’s Ranchi. He has been convicted in all five fodder scam cases in which he was named as a conspirator. Sentencing for Lalu Yadav and the 39 others found guilty may take place on 21 February. He has already been found guilty in four other matters related to the Rs 950 crore fodder scam — the fraudulent withdrawals of Rs 37.7 crore and Rs 33.13 crore from the Chaibasa treasury, Rs 89.27 crore from the Deoghar treasury, and Rs 3.76 crore from the Dumka treasury. So far he has been sentenced to a total of 14 years in prison, but is out on bail for the four convicted cases that involved funds taken by Bihar’s Animal Husbandry Department between 1991 and 1996, when he was chief minister. Life was good till the fodder scam or “chaara ghotala” burst the bubble. That was 2013. Lalu was sentenced to five years in prison and banned from contesting elections. Lalu started off as the youngest parliamentarian by winning the Chhapra Lok Sabha seat in 1977 at the age of 29. Thirteen years later he would rule the state of Bihar. It was the JP movement, named after the Gandhian socialist Jayaprakash Narayan, that became the cradle for leaders like Lalu, Nitish Kumar, Sushil Modi and Shivanand Tiwari to emerge from. [caption id=“attachment_10044161” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Jayaprakash Narayan. Image courtesy oldindianphotos.in[/caption] While riding the anti-Congress wave in 1989, the Janata Dal won 32 of 54 seats in Bihar. His popularity skyrocketed with the arrest of BJP stalwart LK Advani in the first leg of the Rath Yatra in Bihar. He became the messiah of backward classes and Dalits and later pursued the Muslim-Yadav (M-Y) formula. It was due to him that the Janata Dal won 31 out of 54 Lok Sabha seats in 1991 and 22 seats in 1996 parliamentary polls. In 1997, he junked the Janata Dal and floated his own political outfit, the Rashtriya Janata Dal. With the support of 17 Lok Sabha MPs and 8 Rajya MPs, the entire Janata Dal legislature party merged with the RJD in Bihar. Lalu has been criticised enough for “keeping the poor — poor.” Local pundits would often say his tactic was negative but effective to garner votes. That later cost him. The state was branded as poor, backward, directionless and a den of lawlessness. The Lalu-Rabri regime was referred to as “Jungle Raj”. Kidnapping and ransom (aguwah aur phirauti) became catchwords in Bihar. Incidents of doctors, businessmen, and women being kidnapped randomly became rampant. In the 1998 Lok Sabha polls, the RJD retained the tally of 17 Lok Sabha seats in Bihar but performed poorly in 1999, winning only 7 seats. But the RJD won in the 2000 Assembly polls with the support of Congress. It was the year when Jharkhand was separated from Bihar, the Assembly seats in the Bihar Assembly came down from 325 to 243, while the Lok Sabha seats were reduced to 40 from 54. In 2004, Lalu bounced back with 22 Lok Sabha seats, and being a part of the UPA, he became the railway minister. In between 1997 and 2005, the two-time Chief Minister of Bihar made his wife Rabri Devi chief minister of Bihar thrice. Then came the downfall. In the Assembly polls of February 2005, his party only managed to get 75 seats, while the same year in November the number of seats fell to 54. His former ally Nitish Kumar rose to power. Subsequently, from 22 seats in 2004 Lok Sabha, the RJD was just left with 4 seats in 2009. And in 2010 RJD only managed 22 seats in the Assembly elections. Rabri contested from two seats but lost from both. [caption id=“attachment_8979991” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  File image of Bihar chief minister Nitish Kumar. AP[/caption] Despite his conviction in 2013, his party got 4 Lok Sabha seats in the 2014 general elections during the Modi wave. Then another bounce back happened. In the 2015 Bihar state election, he joined hands with Nitish Kumar and Congress. The anti-Modi “Mahagathbandhan” emerged victorious. The RJD emerged as the single largest party, JD-U and Congress secured 71 and 22 seats respectively. But the alliance soon fell apart in 15 months as Nitish Kumar chose to dance with the BJP. In 2019, things got even worse as RJD was not even able to secure a single seat.

***

Also Read **Lalu Prasad Yadav convicted in 5th fodder case: A look at the case, RJD leader’s previous sentences** **Resignation: It’s no more about moral benchmark in politics** **RJD silver jubilee: High and low points the Bihar party went through in last 25 years**

***

I have met Lalu Prasad multiple times in Studio chats over the past two decades. He knew how to work the crowd like the Americans say. He was sharp, funny, tough, and knew how to deliver a soundbyte much better and much before other politicians could catch on. Yet, my most memorable meeting with him was at his Anne Road residence in Patna. I had gone there to persuade him to anchor a show. He met me outside his house in the courtyard in the evening. Sitting on a charpoy with his wife Rabri Devi next to him, Lalu heard the pitch, loved it. My team and I had to inhale the smoke from burning cow dung cakes. This, he said, was required to chase mosquitoes away. Lalu was quite thrilled with the proposal. But for other reasons the show never took off. Lalu, at 73, is not too old but his health is failing. In jail since December 2017, he served most of his sentence in hospital. His son, Tejashwi Yadav, as the chief ministerial candidate of the Mahagathbandhan, is credited with the party’s turnaround in the 2020 Bihar Assembly elections. More importantly, he did not seek votes in the name of his father. The alliance won 110 seats in total out of 243, with RJD winning 75 seats, but falling short of the majority figure of 122. Despite internecine battles that anointed Tejashwi as the torchbearer, Lalu remains a lingering patriarch. Unlike Mulayam Singh Yadav of the Samajwadi Party who has accepted the role of the mentor or “bhishampitamah”, Lalu is yet to officially pass on the baton. [caption id=“attachment_8914771” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  File image of Mulayam Singh Yadav. Getty Images[/caption] Once in a while, you get to see the firebrand back in action. Earlier this month, he stoutly and wittily defended charges of dynasty politics when Prime Minister Modi praised Lalu’s arch-rival, Nitish Kumar, for not bringing any family member into politics. “Modi never had any children. Nitish has a son who is averse to politics. One can only pray that they are blessed with offspring who can carry forward their political legacy,” Lalu hit back. It showed despite being on the ropes his mental toughness was still there. As a throwback, his clarion call used to be: “Vikas nahin, samman chahiye” (we want dignity, not development). Then the dignity and respect for members of specific castes took supreme precedence. Lalu would be leaving behind a chequered legacy. His time as a politician is up. So are his ideas. Now elections are won and lost on planks of development, economic agenda, law and order and of course religion and caste. Lalu won’t be able to tick many of those boxes. The author is CEO of nnis. Views expressed are personal. Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)