Whodunnit? What? Designed the National Flag, of course. Was it the artistic and aristocratic wife of an Indian Civil Service (ICS) officer who was a close associate of India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, in New Delhi? Or, was it a low-profile Gandhian ex-soldier from Andhra Pradesh who had a passion for designing flags? Both contenders are plausible as Nehru was known to entrust important tasks to friends and Gandhi did ‘approve’ a tricolour flag in 1921.

Laila, daughter of the late Badruddin Tyabji (ICS) and Surayya, has always insisted her parents — especially her mother — were not only behind the design of the National Emblem (the Sarnath lion capital) but also the National Flag, both after being (informally!) commissioned to do so by Nehru. Imagine if a PM today decided summarily to give projects of national importance to a favourite civil servant (and/or his spouse) in such cavalier way, without due process?

[caption id=“attachment_11034981” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Badruddin and Surayya Tyabji. Instagram/ lailatyabji[/caption]

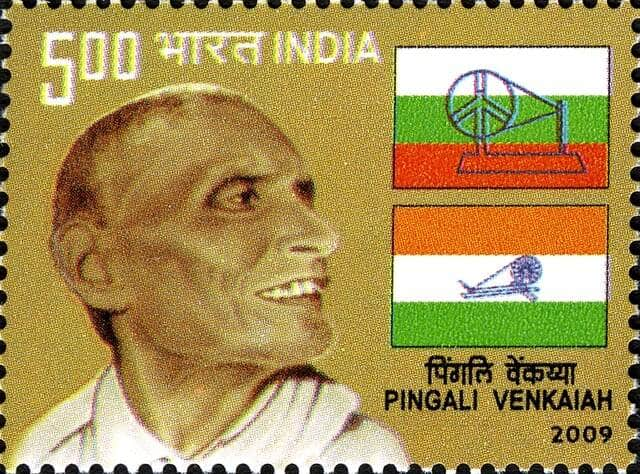

The story now gaining precedence is that an intrepid soldier from south India, Pingali Venkayya, who met Mahatma Gandhi in South Africa and became his follower was so obsessed with designing a flag for India that he finally prevailed! He came up with multiple flag designs and eventually one of them was accepted — with modifications — by Gandhi in 1921 at the Bezwada AICC session and was used from the next year onwards by those involved in the freedom struggle.

[caption id=“attachment_11034991” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons[/caption]

Venkayya died in penury and obscurity while the Tyabjis continued to live a respected privileged existence, so the two narratives and their supporters are expectedly different. Whom the two stories resonate with today is also expectedly different. One speaks of the contribution of a common man to the conception of a national treasure, and the other points to the contribution of a talented and eclectic woman — a spouse of an elite official — to the same cause.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsIn the event, an Ad Hoc Committee on the National Flag had been set up with Dr Rajendra Prasad as the chairman, and included Abul Kalam Azad, C Rajagopalachari, Sarojini Naidu, KM Panikkar, KM Munshi, BR Ambedkar, Frank Antony, Pattabhi Sitaramaiyya, Hiralal Shastri, Satyanarayan Sinha, Baldev Singh and SN Gupta. But Laila Tyabji’s account certainly puts an ad hoc ‘personal’ spin to this story, going by what she wrote in The Wire in 2018:

“Suddenly, people realised India was going to be independent in a couple of months and we needed a national emblem. So, Nehru turned to my father and said, “Badr, you have an eye for this sort of thing, please do something about it.” My father set up a Flag Committee headed by Rajendra Prasad and sent letters to all the art schools asking them to prepare designs. Hundreds came in, all quite ghastly.” What on earth would India have done without the eclectic Tyabjis?

So, the Tyabjis came to India rescue twice, as their daughter has often said and written. It was a “brainwave” of her parents that saw the adoption of the lions and chakra on the Sarnath column as the national emblem. Then they were “tasked” (in what capacity is unclear, but then those were times of Nehruvian exception-alism) with “redoing” the tricolour designed by Pingali Venkayya in 1921. Let no one say the Tyabjis are ungracious with their acknowledgements.

Laila Tyabji says her mother had the first flag sewn by a tailor in Connaught Place—after personally choosing the shades of saffron and green — and painted an Ashok Chakra in blue when her initial black option was nixed by Gandhi himself. It was presented by the Tyabjis to Nehru on 17 July 1947 who apparently attached it to his car and drove past Raisina Hill. What would his colleagues in the Constituent Assembly have thought of that presumptuousness?

A National Flag was undeniably designed and accepted by the Constituent Assembly in July 1947. But did it happen the way Laila Tyabji recalls it, or the way the current government does, is the nub of this ongoing ‘row’ over the flag. Was the flag the result of a “Eureka!” moment of the Tyabjis or the unflagging attempts by an intrepid Pingali Venkayya? The answer appears to lie in the transcript of the Constituent Assembly proceedings of 22 July 1947.

The speech Nehru gave that day to the Constituent Assembly of India with the Honourable Dr Rajendra Prasad in the Chair, reads like a draft of his famous ‘Tryst with Destiny’ oration at ‘the stroke of the midnight hour’ of 14-15 August. The topic, though, was the design and symbolism of the new National Flag. While Nehru uses a (presumably) collegiate rather than royal “we” to describe the process, there is no doubt the flag was not a sudden or 1947 creation.

He said, “I remember and many in this House will remember how we looked up to this Flag not only with pride and enthusiasm but with a tingling in our veins; also how when we were sometimes down and out, then again the sight of this Flag gave us courage to go on. Then, many who are not present here today, many of our comrades who have passed, held on to this Flag, some amongst them even unto death and handed it over as they sank, to others to hold it aloft.”

While Nehru said the Assembly was “only ratifying that popular adoption” he also implied there had been considerable deliberation (by the committee, or did he bypass it for the Tyabjis?) on its constituent parts. “Some people, having misunderstood its significance, have thought of it in communal terms and believe that some part of it represents this community or that. But may I say when this Flag was devised there was no communal significance attached to it.”

He added, “We (presumably he was referring to the entire Flag committee rather than only the creative Tyabjis) thought of a design for a Flag which was beautiful, because the symbol of a nation must be beautiful to look at. We thought of a Flag which would in its combination and in its separate parts would somehow represent the spirit of the nation, the tradition of the nation, that mixed spirit and tradition which has grown up through thousands of years in India.”

Nehru then announced a new element. “There is a slight variation from the one many of us have used during these past years. The colours are the same, a deep saffron, a white and a dark green. In the white previously there was the Charkha which symbolised the common man in India…the masses…which symbolised their industry and which came to us from the message which Mahatma Gandhi delivered. Now, this particular Charkha symbol has been slightly varied.” `

His explanation for this was rather prosaic: a flag had to look the same from both sides and the shape of the charkha is asymmetrical, with the large wheel on one side and the smaller spindle on the other. Thus, on one side the spindle end would point to the pole and on the other it would point outwards. That apparently was not acceptable — unclear why — so they decided to opt for just a wheel instead. And what better wheel than the very symmetrical Ashok chakra?

While Nehru reiterated that “the ratio of the width to the length of the Flag shall ordinarily be 2:3”, he pointed out that “there is no absolute standard about the ratio… Generally speaking, the ratio of 2:3 is a proper ratio but sometimes the ratio 2:1 may be suitable for a Flag flying on a building. Whatever the ratio may be, the point is not so much the relative length and breadth, but the essential design.” A point to remember for Har Ghar Tiranga on 15 August!

Another revelation is that an amendment had been proposed by HV Kamath (of CP and Berar) to include a swastika in the middle of the chakra, to symbolise the “eternal verities of Shantam, Shivam, Sundaram”. But on seeing the design of the chakra — which to him also epitomised the wheel of samsara — Kamath withdrew his proposal. The reaction of Nehru’s international socialist friends (and the west) to a swastika on the new Indian flag can only be imagined!

It is clear from Nehru’s speech that Pingali Venkayya’s design, approved by Gandhi in 1921 as red-green-white with a charkha (modified to saffron-white-green with a charkha in 1931) was the flag used by the Congress to rally Indians during the freedom struggle and became the basis for national tricolour. Who (singular or plural) came up with the idea of replacing the charkha with the chakra is not mentioned, though panel may have decided on its necessity.

As the PM and his family and the Tyabjis went riding together around Lutyens’ Delhi every morning during those idyllic, cosy 1950s (according to Laila Tyabji, at least) Nehru may indeed have turned to them for help on the issue of emblems and flags too. But it is also the lot and the credo of civil servants — and by extension, their families — not to take credit for their principals’ achievements, no matter how crucial their contribution. Rather like speechwriters.

However, when on the first hour of 15 August 1947, the first flag of India was presented to Dr Rajendra Prasad by Hansa Mehta on behalf of “the women of India”, among the 74 other ladies there (including several female members of the extended Nehru clan) was Surayya Tyabji. Maybe she was there for her contribution to the emblem and flag; maybe because she was the wife of a well-connected ICS officer — there is no way to know for sure.

There is enough evidence of Nehru’s reliance on ‘family and friends’ for crucial official projects, invariably bypassing procedures. But there should be space in Indian hearts to accommodate the contribution of one humble person from outside Delhi’s charmed circle — Pingali Venkayya — as well one exalted person within it — Surayya Tyabji — when it comes to the design of our National Flag. The most important point, after all, is to ensure our Tiranga always flies high!

The author is a freelance writer. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)