Sometimes, to understand the global geopolitical undercurrents at a slightly deeper level, all you need is a set of maps – old and new. Though Halford Mackinder considered map as a “whole series of generalizations” – subjective, and often a co-conspirator in hiding the whole truth, Robert Kaplan – despite being a fan of geography more than randomly drawn political lines on a map, considers that a state’s position on the map is the first thing that defines it; governance, ideology and worldview often follow later. And while this essay is not about maps, this bit of backdrop is necessary because those that wish to understand what a country like Turkey is trying to achieve, would need two Eurasian maps – a current political one, and an old map of the pre-WWI Ottoman empire.

Expand to Survive

Expansionist tendency is a precursor to dominance. What would Christianity or Islam be without an expansionist outlook? Confined to some rocky wilderness in Levant, or hiding in the deserts of Arabia perhaps. The few Christians or Muslims that would make it to Europe would probably be discriminated against and ghettoised like the Jews. Aggressive expansionism – whether in thought or in action – is to rid oneself of a conceptual weakness; if one (with that kind of a weakness) doesn’t expand, one withers (recall Lebensraum). For the same reason, historically both Christianity and Islam have always tried to expand; though off-late it seems Europe – as the flagbearer of Catholicism, and Protestant-world leaders USA-UK have given up hope in the face of persistent Islamic expansionism of the 21st century.

Interestingly, Islam’s potential for global dominance has been matched equally by their internal schisms and sectarian fault lines that developed over time. From the initial all-encompassing Ummayid or the Abbasid, to the later day Persians, Ottomans, smaller entities like central Asian Khanates, or the Mughals, and finally to the more modern Morocco, Egypt, Turkey, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Pakistan etc, the cracks have only multiplied with time.

That is what would make the trials for an imperial rerun of Turkey (post 2023 elections) incredibly interesting to watch.

Why Turkey?

The instability within the Islamic world has always kept open the chance of a dominant nation to rise up to assume the mantle. This is so real a possibility that the world has even witnessed non-state entities like Al Qaeda or ISIL try to establish random caliphates here or there. They have failed, and will continue to fail perhaps, but that wouldn’t overrule the fact that the results could be quite different if it were a nation-state with a long-term strategy in place. Turkey looks like it is best suited for the job, and they know it.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsIndonesia and Pakistan are two of the largest Muslim populated countries, but are they cut out for the role? We know Indonesia doesn’t have the will. And Pakistan doesn’t have the wherewithal. A map comes handy during these moments. Pakistan is too close to bigger regional powers like China, India, Russia, or Iran – there is no wriggle-room; nowhere to expand other than Afghanistan, which has translated into a failure after the Taliban chose to go its own way. Under such compulsions, Pakistan’s nuclear ability, or its ties with China take a backseat.

The next in line are Iran, Egypt, and Turkey. Iran – though superb in administration, execution, influence, and an okay economy, for some reasons is always in the crosshairs of the US. The constant US sanctions and Tehran’s trials to find out elusive windows of opportunities have kept them on their toes. Other crucial restraining factors are KSA and Sunni Wahhabism being on a warpath with Shi’ite Iran, and Israel as a source of constant (and substantial) irritation. Then there is the map. With KSA in the West, Iran faces Russia – with a history of a complicated relationship right from the Persian times – up northeast, Turkey along northwest; and because the Persian Gulf is extremely important for the Western world, there is always a larger-than-life US interest there. Egypt has stopped trying to project its power since some time now; and with significant inroads made by Turkey-influenced Muslim Brotherhood post-Tahrir Square, Egypt remains under-prepared for the task.

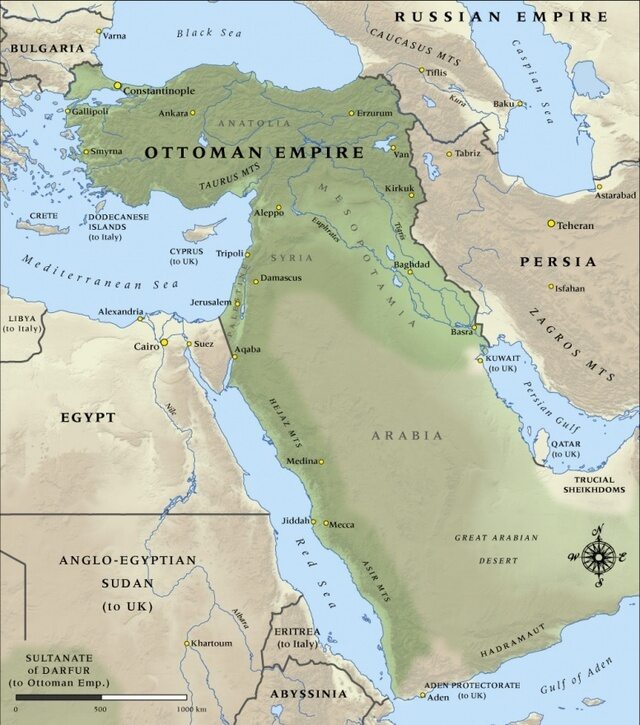

Turkey has several advantages that President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan understands quite well, and intends to exploit them (and in the process he has created some new ones too). Turkey is a big economy. It is a modern economy, and much bigger than Egypt or Iran. It is not doing well presently at a macro level, but it remains one of the economies to grow fastest post-COVID, and is probably equipped to handle the present crisis. Geographically, Turkey has ample wriggle room along all sides – a pre-WWI Ottoman map provides vital clues. Being the centre of the Ottoman Empire, present-day Turkey has regional influences along tracts of North Africa, the Middle East, Caucasus, as well as parts of Eastern Europe, aside from direct access to open water through the Mediterranean Sea, and a history of naval strength. The other important aspect is that Turkey is a part of NATO, has one of the biggest standing armies among NATO members, and it has rudiments of a working relation with Russia despite being a part of the Atlanticist group. Turkey; because Turkey is best suited.

[caption id=“attachment_10971301” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

This map shows the boundaries and major cities of the Ottoman Empire at the start of the First World War in 1914. Image courtesy: nzhistory.govt.nz[/caption]

This map shows the boundaries and major cities of the Ottoman Empire at the start of the First World War in 1914. Image courtesy: nzhistory.govt.nz[/caption]

From Kemlism to Islamism

Of the many reforms that Kemal Ataturk spearheaded, a key one was the expansion of the Law of Fundamental Organization, which served as the unofficial constitution of Turkey before him. This expansion kept in mind the structural weaknesses of the Ottomans: Religion and religious elites who enjoyed all advantages – which was against Kemal’s secular core; and a voiceless citizenry that was a result of the former weakness, and one that led to the different nationalist and breakaway movements. Kemal addressed these two by creating a secular and democratic Turkey. And in order for that democracy to perform optimally, Kemal reduced the scope of political authority of any one individual by way of empowering the Grand National Assembly and delineated power by creating a number of laws and processes designed to keep accumulation of power in check.

[caption id=“attachment_10971341” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

File image of banners showing modern Turkey’s founder Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, left, and Turkey’s current President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, right, decorate a building as people watch Erdogan’s speech, during a rally for the upcoming referendum, in his hometown city of Rize, in the Black Sea region, Turkey, in April 2017. AP[/caption]

File image of banners showing modern Turkey’s founder Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, left, and Turkey’s current President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, right, decorate a building as people watch Erdogan’s speech, during a rally for the upcoming referendum, in his hometown city of Rize, in the Black Sea region, Turkey, in April 2017. AP[/caption]

President Erdogan changed all of that. Following the failed coup on his Presidency in July 2016, Erdogan introduced the new constitution of Turkey by bringing in amendments that significantly weakened the powers of the prime minister, the Turkish Parliament, and not only vastly increased the presidential powers, but also altered the election pattern; the president, instead of being elected by the Grand National Assembly was to be elected by direct public votes from then on. Additionally, he could appoint or dismiss ministers, public officers, bureaucrats, declare emergency, unleash violent powers all along without being neutral as the head of state – for the president of Turkey, under the amended constitution remained free to retain ties to a political party of his choice.

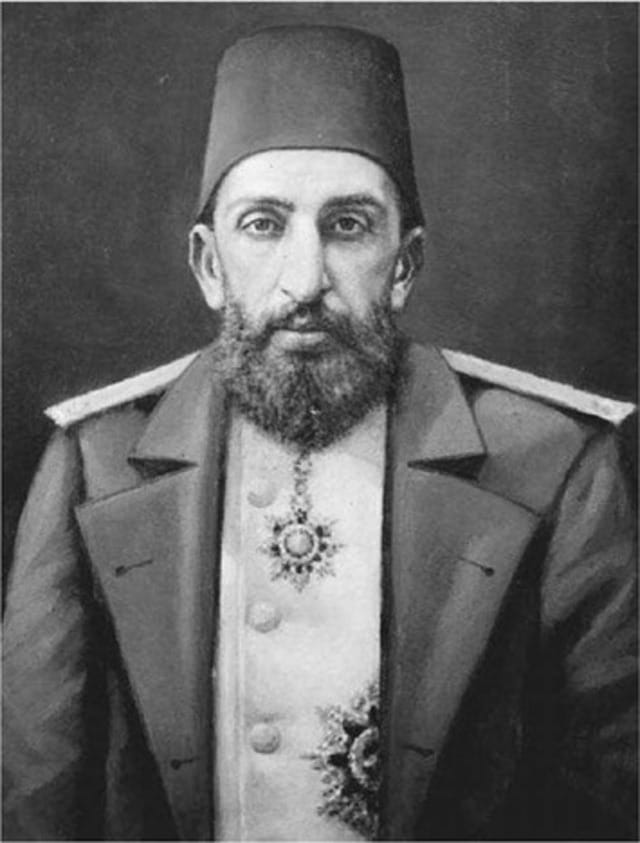

One could find reflections of this in Ottoman history. The empire did try to modernise in the face of competition from industrial Europe, Imperial Russia, and the rise of nationalist sentiments among the Greek or Serbian subjects. Unlike during the times of Kemal Ataturk, this effort to modernise did not work well and the empire regressed back to its traditional ways of governance. This was the 19th century – during the time of Sultan Abdelhamid II. Erdogan is on the same path.

[caption id=“attachment_10971401” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

File image of Sultan Abdelhamid II. Wikimedia Commons[/caption]

File image of Sultan Abdelhamid II. Wikimedia Commons[/caption]

Show of Hard-Power

Is Erdogan an Abdelhamid fan? Professor Alan Mikhail of Yale University (author of Gods’ Shadow: Sultan Selim, His Ottoman Empire, and the Making of the Modern World) is of the opinion that the one sultan that Erdogan is a fan of, is the empire’s ninth sultan Selim I, during whose reign the Ottomans mutated from being a regional power to a huge empire. The three aspects of Selim I and his rule (ones that Prof Mikhail warns the world to watch out for in President Erdogan) are:

Strongman politics that led to regional wars

That reflects in the way Erdogan has grown increasingly aggressive in Kurdistan, Syria, Libya, or Greece and Cyprus. He has sent troops to occupy/control 8000 square kilometers of northern Syria. He has intervened in the Libyan civil war. He is stoking the Greco-Turkish dispute now that the Treaty of Lausanne (over Cyprus) is ending in 2023. Analysts have expressed this to be in preparation for a gradual takeover of the Turkish half of Cyprus. And he has also been found pushing Azerbaijan in its short war against Armenia (that is theoretically under Russia influence), perhaps to challenge Russian primacy in the Caucasus.

Attempted annihilation of religious minorities

Erdogan has been targeting the Turkish Shi’ite, Christians, Kurdish population, and even journalists or dissenting voices, while at the same time developing Sunni hardliners to buttress a Turkish identity that resonates with the Ottoman era. Besides, he has established ties with Muslim Brotherhood; he has been found accommodating the Syrian rebels or the ISIL terrorists (read this report by Emily Milliken); and he has also made public his preference for the Hamas .

Monopolisation of global/regional resources

Reflects in the way Erdogan has been on an overdrive trying to grab the natural gas resources around Turkey – whether in Syria, Libya. He is also expected to initiate Black Sea drilling for gas in 2023. Turkey acts as a tap in the European immigration crisis among others, controlling the flow of Muslim refugees into the EU. Western Europe already has a steady population of second and third generation Muslim North African and Turkish settlers, and Erdogan is pushing for Islamic political parties in different European nations.

The author is a geopolitical enthusiast and the author of Journey Dog Tales, The Puppeteer, and A Matter of Greed. He tweets at heartland_ari This is the first of a two-part series. Check back on Sunday to read the second part of the analysis of Turkey’s expansionist tendencies Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram .

)