Three years ago in 2020, in the darkness of the intervening night of 15 and 16 June, Chinese troops armed with primitive weapons launched a vicious attack on Indian soldiers at the Galwan river valley, shattering the peace and tranquility painstakingly stitched up since 1988 and causing the first loss of lives due to violence at the India-China border since 1975. What lessons have India learnt from the debacle that saw the death of 20 Indian soldiers and an unspecified number of Chinese troops? The first point is rather counterintuitive. India has been a victim of its own success.

This needs elaboration. What happened in Galwan is the direct consequence of India’s major push to dramatically improve border infrastructure and reduce the force asymmetry that marked the LAC with China. This isn’t to argue that India erred by adopting the strategy, but to point out the dichotomy inherent in a ‘security dilemma’.

The precarious peace at the LAC that marked the years up until the three-week Depsang standoff in 2013 was built on agreements and mechanisms that kept the border calm but also locked in the logistical superiority, infrastructural advantage, and military edge that China enjoyed. Operating from the Tibetan plateau China already has the topographical advantage, unlike India that must pave its way through the daunting Himalayas, and thanks to massive investment in border development over decades, Chinese troops enjoyed a mobility and force posture that its Indian counterparts found hard to match.

This difference in force asymmetry made for a perverted deterrence strategy from India based on “inaccessibility”.

Speaking to the media during a briefing on ‘nine years of Narendra Modi government’, external affairs minister S Jaishankar alluded to India’s erstwhile self-defeating strategy as a “severe disadvantage”. “…People make out as though something is happening now. It has been happening for a period of time. And we need to focus on what our border infrastructure is. How do we deploy our military? How do we maintain that deployment out there? And a lot of our forward deployment problems are because border was so badly neglected. I mean, I don’t want to go into those famous statements that our best defense is neglect of the border so that other people can’t come forward. But the result was our own troops were very severely, I would say, disadvantaged when they had to respond…”

Quick Reads

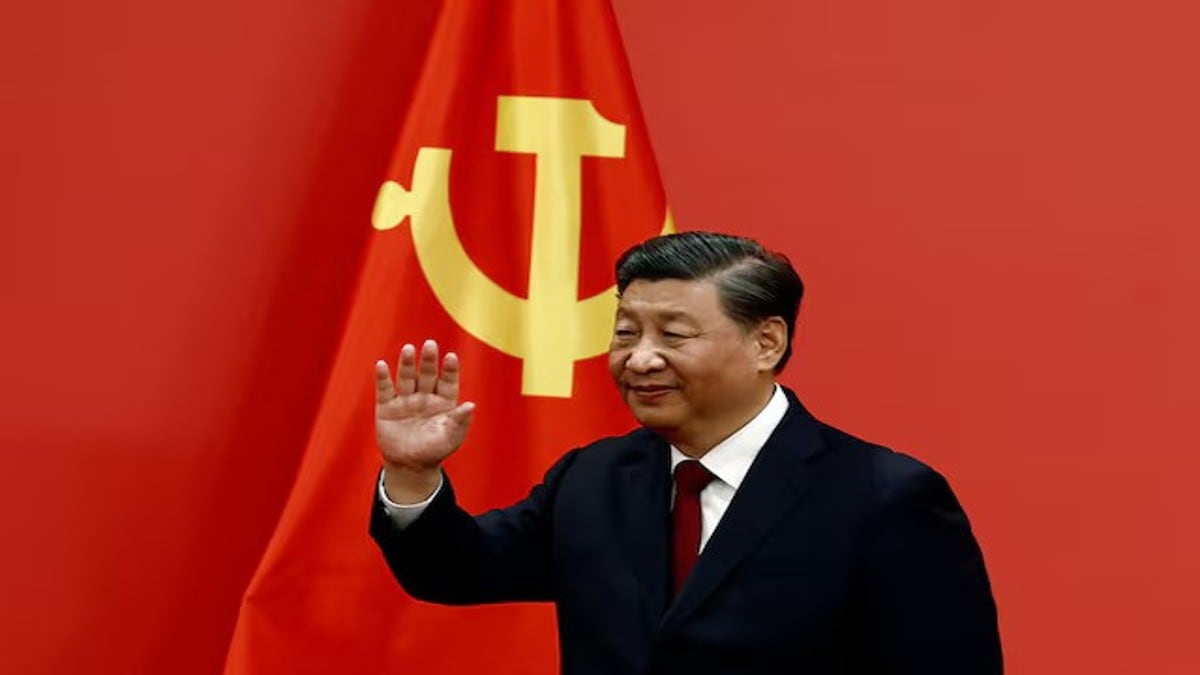

View AllOne year after the Depsang valley standoff, China again hiked the pain point for Indian soldiers at the Chumar sector in September 2014, a face-off that continued for over two weeks when rival troops were eyeballing each other at sub-zero temperatures, ironically at the time when Chinese president Xi Jinping was being hosted by prime minister Narendra Modi.

It was evident from both instances that China possessed the wherewithal to control escalation at the LAC through unilateral transgressions, coercive tactics and creation of fait accompli, at least a part of which is due to the better mobility that the PLA enjoyed.

To tackle repeated Chinese ingress that was designed to test India’s red lines, the Modi government in 2014 embarked on an infrastructure drive eye-wateringly big and ambitious — with an expeditious time frame to boot — to reduce this power asymmetry. What kind of drive are we talking about?

The BJP-led NDA government tripled its spending on border infrastructure and doubled its construction rate of roads, tunnels, habitat shelters and operational logistics. Quoting data from the ministry of road transport and highways, media reports indicate that from “0.6 km of national highways built a day during the UPA era (2009-14), road construction more than doubled during the NDA regime, touching an all-time high of 1.5 km a day between 2014 and March 2019” that includes 2,731 km of national highways across the eight Northeastern states between 2014 and 2019 built by central agencies such as NHAI and the BRO.

One of the big decisions taken by the Modi government as soon as it came to power in 2014 was to issue a blanket environmental clearance for construction of roads within 100-km aerial distance from LAC. On the back of that political intent, while the UPA government built 3,610 km roads in the period between 2008-14, the Modi government constructed 4,764 km roads in the six-year period between 2014 and 2020.

Economic Times, citing government data, observed in a report that between 2016 and 2020-21, the allocation for upgradation as well as building of new roads and bridges along the LAC went up from Rs 4,600 crore to Rs 11,800 crore. To understand the quantum of the increase, we need to look at previous figures. Between 2008 to 2016, the government spending on these roads increased by just Rs 1,300 crore from Rs 3,300 crore in 2008 to Rs 4,600 crore in 2016, according to the report.

There’s more. “Formation cutting” involving fresh digging, blasting and earthworks increased from 230 km-a-year in the decade until 2017 to 470 km between 2017-20, while “road surfacing rate” went up from 380 km-per-year in the same period from 170 km-per-year in the past decade, observed the newspaper.

The government told the Rajya Sabha in a written statement in 2022 that in the last five years since 2017, the Centre has constructed all-weather roads measuring 2,088 km along the India-China border to improve connectivity and facilitate all-weather access to forward areas at an overall cost of Rs 15,477 crore. If roads constructed along India’s borders with Pakistan, Myanmar and Bangladesh during the same period are taken into account, the cost jumps to Rs 20,767 crore.

If anything, the pace of road building and allocation of funds have been ramped up even more. According to data from the defence ministry, BRO’s capital outlay was ramped up by 40% to Rs 3,500 crore in FY 2022-23 from Rs 2,500 crore in the previous fiscal to expedite creation of border infrastructure including tunnels (Sela and Naechiphu) and bridges on major river gaps. It witnessed another 43% increase to Rs 5,000 crore in the 2023-24 budget.

The last three years, particularly, have seen a frenzied push for upgradation of roads, bridges, tunnels, helipads, tracks and other assorted military infrastructure. According to the Indian Express, that cites official data, the BRO “completed 19 infrastructure projects in 2021 and 26 in 2022 in Ladakh alone. It has set a target of completing 54 projects this year. These include roads and bridges among other miscellaneous projects.”

As the foreign minister pointed out during the recent presser, “the average border infrastructure budget till 2014 was less than 4,000 crores. Today, it is 14,000 crores. If you look at road, you look at tunneling. You look at bridges… it’s gone up twice, thrice, four times. Look at even the equipment for our military. So instead, actually, we had even people trying to build border infrastructure, you remember all those environmental problems, clearances, which earlier on became an issue…”

The flip side of this intense infra push is an escalation trap that theorists in international relations call the “security dilemma”, whereby sovereign states in a competition to become more secure and fortify themselves, ramp up military spending, infrastructure and even strike alliances only for competitors to follow suit, resulting in a spiral of increased capabilities and ironically, degraded security environment.

If we interpret the actions of India and China through this prism, it may explain why both states are locked in an escalatory spiral and chances of friction are increasing manifold. In this context, India’s renewed push to reduce the power asymmetry with China and challenge the PLA’s area dominance has ironically alarmed Beijing even more, leading to competitive force postures along the LAC.

The second lesson from Galwan, related to the security dilemma is that the sheer troop density (about 50,000 to 60,000 men on each side) and the forward deployment of Indian and Chinese soldiers — armed to the teeth and backed by advanced weaponry, permanent habitat, artillery, air support and air defence systems — has increased the chance of skirmishes that may quickly turn into deadly kinetic action. Both sides may find such a spiral hard to control.

As former career diplomat and former Indian ambassador to China, Ashok Kantha, has said in an interview with ABP Live, China has turned a relatively tranquil LAC into a “live border” and has created “a situation where there is deployment of troops in close proximity and in escalated numbers (that) is inherently risky. It can lead to accidents. It can lead to unintended consequences. I believe that neither India, nor China is inclined to move towards a military conflict. But you cannot rule out unanticipated developments, you cannot rule out accidents.”

The logic of ‘security dilemma’ holds that unless there is an understanding between both sides, there will be no unilateral disengagement or de-escalation. India believes that it has been forced into a forward deployment to establish deterrence against low-level coercive tactics and ‘salami slicing’ of its sovereign territory by Beijing, whereas to China, India’s increased spending and ramping up of infrastructure is a ‘provocation’ that must be addressed. For this reason, the crisis is nowhere close to getting dissipated and the threat of future clashes looms large.

According to the foreign minister, “the main point is that along the LAC, there is patrolling, where our military goes out from their bases, patrol, and then returns to base. After 2020, this changed because when they violated the 1993 and 1996 agreements and brought a large number of troops, instead of patrolling and returning, we had to resort to forward deployment. The problem now is the issue of forward deployment because both sides are forward deployed. And as I explained earlier, tension arises from forward deployment itself.”

The third lesson from the Galwan incident is that India lacks the leverage to force China to break the deadlock, and the dialogue mechanisms are proving ineffective. After 18 rounds of military discussions and 27 round of meetings of the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India-China Border Affairs (WMCC) the standoffs still continue at Depsang in Daulet Beg Oldi sector and Charding Nullah Junction in Demchok.

Parsing the foreign minister’s comments at the presser, where he said that “we have to, you know, the two of us (India and China) have to find a way of disengaging, because I don’t believe that this present impasse serves China’s interests either. The fact is the relationship is impacted, and the relationship will continue to be impacted. If there is any expectation that somehow we will normalize while the border situation is not normal, that’s not a well-founded expectation.”

India believes that by tying the health of the larger bilateral ties to restoration of peace and tranquility at the border will eventually pay dividends — and recent indications from within the defence establishment suggests that India is ready to play the waiting game while ramping up surveillance and military preparedness — the fact is that China is perfectly happy to let the current situation lapse into the ‘new status quo’ because despite the chill in bilateral ties, two-way trade is booming to China’s advantage.

This will take time and patience to reverse, since India is at a development curve where reversing such deep trade deficits isn’t easy. What India shouldn’t do, despite agenda-driven bluster from a section of its own commentariat that advocates warmongering with China to achieve its perverse political objectives, is rush the breaking of deadlock. Two can play the game.

Read all the

Latest News,

Trending News,

Cricket News,

Bollywood News,

India News and

Entertainment News here. Follow us on

Facebook,

Twitter and

Instagram.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)