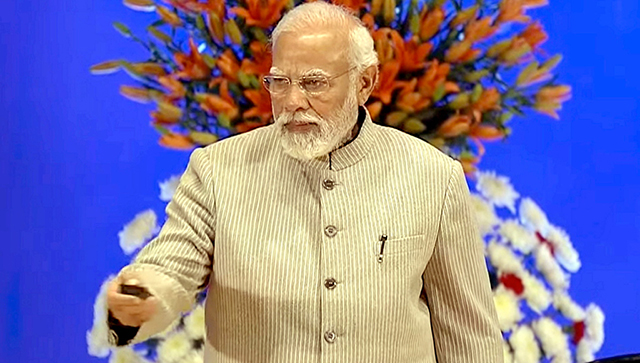

Financial Times, the London-based daily that carried the “scoop” on an alleged plot by India to take out a Khalistani terrorist in the US, published a long, exhaustive interview of Prime Minister Narendra Modi Thursday on a range of issues, including the controversy that has driven a wedge between New Delhi and Washington. There are several points about the interview that need to be highlighted, especially FT’s sly attempt to editorialise what should have been a straightforward question-and-answer format, disseminate disinformation and create straw man arguments to push insidious narratives, but before I highlight the British daily’s semantic chicanery and analyse the prime minister’s responses, one point must be made upfront. In deciding to answer freewheeling questions from one of his toughest critics, a provocative, India-baiting lodestar among Western media outlets, Modi has demolished the notion that he shies away from the media. Throughout the queries — some of which were deliberately deceptive to hammer home lazy western tropes on a democratically elected government and its leader who comfortably beats global peers in popularity ratings even after nearly 10 years in power — the prime minister consistently avoids the ambushes, sets the narrative, and forces the game to be played on his terms. Let’s give an example. The newspaper does not provide the text of the specific question that was asked. It offers instead the foggy paraphrase of a loaded query which attributes to the unquantifiable, unverifiable “some” a narrative that India won’t be able to “replicate China’s manufacturing-led economic take-off” due to “corruption, administrative hurdles, and the skills gap among youth” that are apparently the talking points of unnamed Indian and foreign companies. To this manipulative ploy, Modi replied: “You have done a comparison with China, but it might be more apt to compare India with other democracies… It’s important to recognise that India wouldn’t have achieved the status of the world’s fastest-growing economy if the issues you’ve highlighted were as pervasive as suggested.” The coup de grâce came in the subsequent sentence. “Often, these concerns stem from perceptions, and altering perceptions sometimes takes time.” The newspaper hived off in a separate piece questions on the American allegation against India, made at a New York City court by the US Department of Justice in an indictment that alleges that a serving Indian intelligence official was involved in a murder-for-hire plot to assassinate Khalistani terrorist Gurpatwant Singh Pannun on American soil. Modi’s answers may be summarised in a few broad points. In his first response to the allegations, Modi makes it clear that US-India bilateral ties are far stronger, resilient and broad-based to be derailed by a “few incidents”. Interestingly, he issued no outright denial but a promise to investigate the charges, if any evidence is put forward, implying thereby that the indictment in itself has no evidentiary value. Let’s first take a look at his responses to the questions that once again are not made clear. “If someone gives us any information, we would definitely look into it,” Modi said. “If a citizen of ours has done anything good or bad, we are ready to look into it. Our commitment is to the rule of law.” He said India was “deeply concerned about the activities of certain extremist groups based overseas… These elements, under the guise of freedom of expression, have engaged in intimidation and incited violence.” On bilateral ties, he highlighted that “there is strong bipartisan support for the strengthening of this relationship, which is a clear indicator of a mature and stable partnership. “Security and counter-terrorism co-operation has been a key component of our partnership… I don’t think it is appropriate to link a few incidents with diplomatic relations between the two countries.” Evidently, India’s focus remains clear on continuing with the pace, scale, and trajectory of its relationship with the US which is mature and stable enough to handle a few glitches, the allegations that have been dubbed “serious” by Washington are downplayed, indicating an attempt to sandbox the crisis, and an unequivocal promise has been made to uphold the rule of law since India is committed to it. At the same time, a careful reading of Modi’s response reveals a total rejection of the core allegation that a serving Indian officer was involved in the controversy. The prime minister says, “If a citizen of ours (not official) has done anything good or bad, we are ready to look into it.” In light of the detention of an Indian citizen, Nikhil Gupta, who now lives in the custody of Czech authorities pending extradition to the US, the prime minister makes it clear that legal wrangling, if any, would centre around the purported citizen (Gupta) provided enough evidence is provided by the US side, but beyond that nothing. The prospect of CC-1 (the ostensible Indian serving officer involved in the scandal according to the indictment) is not up for negotiation or even discussion. While Modi stresses that relations remain on an “upward trajectory”, and that the “relationship is broader in engagement, deeper in understanding, warmer in friendship than ever before,” that shouldn’t be held hostage to one incident or two, there is a subtle message that the US cannot dictate terms to India, or expect New Delhi to play the role of an obedient subordinate. New Delhi sees itself as America’s partner, a stable, dependable one that seeks to profit from and provide benefits to the relationship in a quid-pro-quo based on mutual trust, but, as this columnist wrote in a recent piece , Washington must understand “that not all partnerships may follow the hub-and-spoke model where American security guarantees will be made at the cost of submission, subservience and transfer of a degree of sovereignty.” As Modi makes clear in a subsequent response, “We need to accept the fact that we are living in the era of multilateralism… The world is interconnected as well as interdependent. This reality compels us to recognise that absolute agreement on all matters cannot be a prerequisite for collaboration.” The prime minister also fixes the focus firmly on the threat to India’s national security and territorial integrity posed by the Khalistani separatists whom he branded as “extremist groups based overseas” — with an implicit accusation that the West has turned a blind eye to India’s concerns under the guise of “freedom of expression”. India is making it clear to the US that if the Americans value the strategic partnership, they should put up their end of the bargain by acting against terrorists who threaten India’s security. Failing to do so while demanding obeisance from India will not work. What comes out from the interview is the undoubted discourse power of the West that allows western media to place itself as the arbiter of ‘truth’ and the ayatollah of objectivity all the while actively subverting both. This narrative control, however — as the Modi interview shows — coming under increasing strain from a rising India which is not ready to accept the role of a supplicant of a great power and has an alternative civilisational praxis and a framework to offer to the world. What held India back so far was its need to address endemic poverty with limited resources, hamstrung by disastrous policy decision in the first decades of its journey as an independent, Westphalian nation-state. As India grows in strength, pulls more people out of abject poverty and strides towards a moderately prosperous society, its emergence as a modern democracy from a semi-feudal system becomes fuller, the old tropes of defining India through the western lens would become inadequate and even erroneous. We see these mechanisms employed from the very first paragraph of the interview when the tone is set by seemingly innocuous detail such as Modi changing the name of Race Course Road, where the prime minister’s official residence is located, to Lok Kalyan Marg or “People’s Welfare Street”, “a name more in keeping for a twice-elected leader with populist leanings and a flair for discarding the trappings of India’s colonial past.” A name that rings truer to Modi’s politics is somehow reduced to a ‘populism’ pejorative, and the very next paragraph points out the lavishness of the prime minister’s residence with “parading peacocks,” “inner courtyards with ornate flower displays”, “meeting rooms boasting of maps of the world painted on ceiling frescoes,” to convey the contrast between kalyan (welfarism) and reality (opulence). The subtext is that the prime minister’s residence must reflect modesty, even squalor or else the welfarism is fake. This, of course, is not spelt out but the lexical subterfuge makes it abundantly clear. A similar rhetorical ploy is employed to describe the prime minister’s sartorial choices and even personal hygiene. “‘Today, the people of India have very different aspirations from the ones they had 10 years back,’ says Modi, dressed in a cream kurta and rust-coloured sleeveless jacket, and immaculately barbered and manicured.” As analyst Sagorika Sinha points out, “how dare an Indian Prime Minister from the backward classes, who once sold tea in a chai-stall, and still connects with the construction workers and village women of his country, be quite so well-dressed and have well-appointed residences and, gods forbid, a manicure?” Or, take the line when FT, in one of its countless commentaries that mark the interview, casually puts forth that it from his “quiet residence that Modi has managed India’s growing international influence but from where, in the view of many of his domestic opponents, he could also represent a risk to that constitution.” A leader who enjoys soaring popularity at the completion of two successive terms and remains the absolute favourite to clinch a third term through democratic mandate somehow poses a “risk to the Constitution”, implying that voters who may opt for Modi again in 2024 would end up endangering the Indian Constitution. The bunch of leaders who collectively form India’s Opposition may be driven by desperation to float such a narrative but it’s not clear that the vast majority of voters shares that perspective. Parroting the Opposition’s talking points without even a modicum of research sits at odds with the claim of venerable ‘pink newspaper’ from Britain that fashions itself as a serious daily, but such is the pressure of narrative building that it has to be done. In another segment of commentary that intersperses the interview, the newspaper writes, “His opposition, led by the Indian National Congress and MPs including Rahul Gandhi, have joined forces in an alliance under the acronym I.N.D.I.A., which promises to “safeguard democracy and the constitution” in the face of what they say is an attack on the secular principles of the country’s founders. During his nearly 10 years in office, critics have accused Modi’s government of cracking down on rivals, curtailing civil society and discriminating against the country’s large Muslim minority. Modi’s opponents worry that he would use a third-term victory, especially if the BJP wins a large majority, to shred secular values irrevocably, possibly by amending the constitution to make India an explicitly Hindu republic.” The forces that FT designates to be custodians of democracy are habitual election deniers when results don’t go their way, taking recourse to a defeatist campaign against EVM — complaints that miraculously evaporate when the Opposition comes out on the winners’ side. One of the reasons that voters have put their trust on Modi is that he is perceived to be incorruptible. This is one more vulnerability that plagues the Opposition as its leaders — be it the Trinamool Congress in West Bengal, Congress Party or the DMK in Tamil Nadu — are frequently found neck-deep in corruption. The interview never bothers with these nuances. It instead calls Rahul Gandhi “the BJP’s chief political nemesis”, reflecting a stunning ignorance of ground realities in Indian domestic politics. The one leader who has consistently failed to live up to expectations, displayed his disinterest, even disdain for politics and power multiple times, has led Congress to two disastrous results in consecutive Lok Sabha elections, had to give up his family’s seat in Uttar Pradesh for a ‘safe seat’ in Kerala and yet continues to be propped up by the Congress Party and a family that fears an existential crisis without a Gandhi scion at the helm, is a “nemesis”. FT’s disdain for India’s place in the global comity of nations leaks through despite a careful manicuring of the narrative. It frequently falls back on frivolous tropes such as India’s “democratic backsliding” under Modi, which it claims, “have alarmed some observers in India and overseas at a time when leaders around the world are betting heavily on the country as a geopolitical and economic partner.” It is India which should be concerned instead over a worrisome democratic backsliding in the US, its closest strategic partner. The recent decision by a court on Colorado, US, to invoke a little-known insurrection clause and disqualify Republican frontrunner Donald Trump from the state’s presidential ballot, represents fundamentally undemocratic action by a heavily politicised court whose judges are appointed by Democrats. This, as Republican senator Marco Rubio has pointed out on X, represents a situation where “The U.S. has put sanctions on other countries for doing exactly what the Colorado Supreme Court has done today.” The prime minister played it with a straight bat. “Our critics are entitled to their opinions and the freedom to express them. However, there is a fundamental issue with such allegations, which often appear as criticisms,” he says about concerns over the health of Indian democracy. “These claims not only insult the intelligence of the Indian people but also underestimate their deep commitment to values like diversity and democracy… Any talk of amending the constitution is meaningless.” The FT narrative-peddling would remain incomplete without the customary invoking of the “Muslim minority being oppressed by a Hindu national regime” trope. It was duly raised, and Modi answered it by raising the economic success story of India’s Parsees, a “religious micro-minority residing in India”. “Despite facing persecution elsewhere in the world, they have found a safe haven in India, living happily and prospering,” Modi says, in a response that makes no direct reference to the country’s roughly 200mn Muslims. “That shows that the Indian society itself has no feeling of discrimination towards any religious minority.” Ironically, the newspaper itself admits that Muslims number over 200 million, making them the largest minority in India and one of the largest Muslim population in the world. Under Modi, India’s relationship with Muslim nations, including the Arab states has substantially improved and intensified and Modi has been conferred with highest civilian honour by a number of Islamic nation. Dropping dark hints about the fate of Muslims in India, without furnishing even one relevant fact, painting the Muslim population in India as victims of oppression at a time when they are being made an integral part of the India growth story befits a publication that has made spreading disinformation on India its singular mission. The interview sought to ‘expose’ Modi, but the disingenuous hypocrites got exposed instead. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views. Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

The prime minister avoided the ambushes, set the narrative and forced the game to be played on his terms

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)