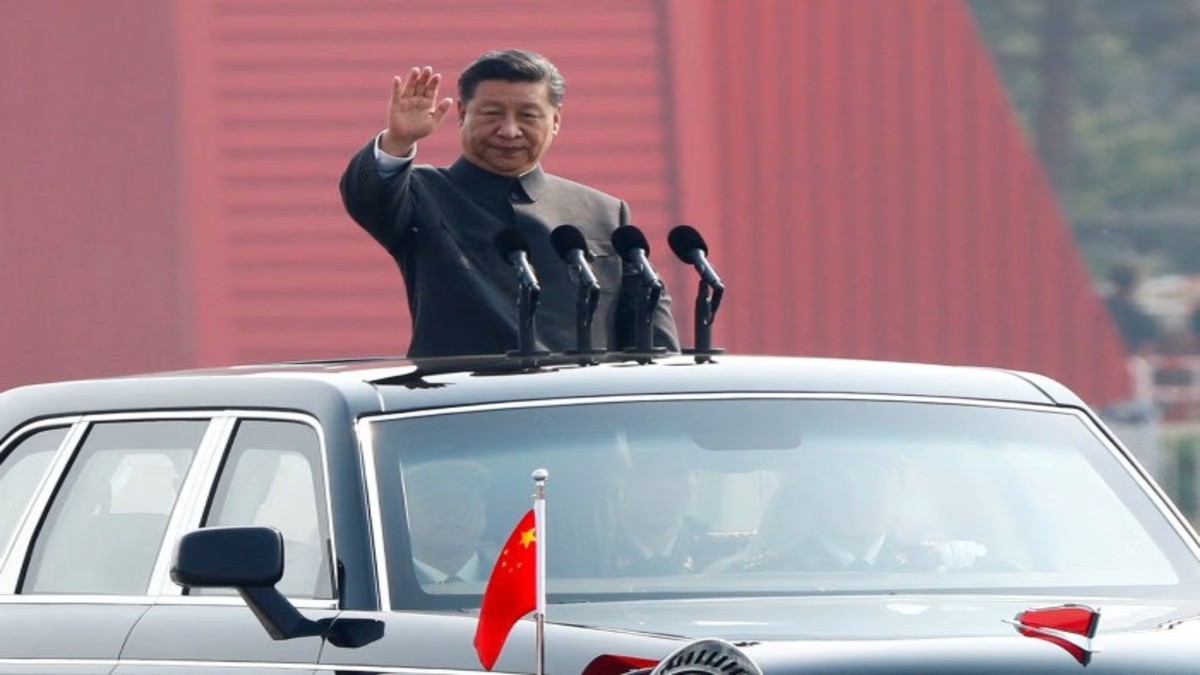

On September 3, Chinese President Xi Jinping addressed his people and the foreign leaders who had gathered in Beijing to attend the military parade on the occasion of what China described as the “80th anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War”, or, as it was called in the popular media, the ‘Victory Day’ parade. It was attended by heads of state or government of 26 countries, including Russia and North Korea. Their leaders were given special status.

Among others who were present were three South Asian leaders, from Pakistan, Nepal and the Maldives. The Central Asian leaders were all present. So were some from Asean and Africa. Significantly, Japan had actively lobbied countries against attending the parade.

In his speech Xi extolled the valour of the Chinese people in their struggle against Japan. From there he went on to praise the people’s determination to maintain the founding principles of the People’s Republic, which was established in 1949 with the victory of the Communist Party under Mao Zedong.

Since then, while the Party has changed developmental strategies, it has remained firm on maintaining socialism with ‘Chinese characteristics’ as well as maintaining complete control on all aspects of the country’s national life. Turning to foreign policy, Xi said in his address, “History cautions us that humanity rises and falls together. Only when all countries and nations treat each other as equals, coexist in peace and support each other can we uphold common security, eradicate the root cause of war and prevent the recurrence of historical tragedies.”

The army parade was held on a grand scale. China displayed its military advances, including its nuclear triad. The spectacle’s purpose was to demonstrate that China was now a global power, in the same bracket as the US. Indeed, the parade was yet another indication for China to assert that no power was in its league apart from the US. That was the clear message to those countries, including India, which assert that the world has become multipolar. Whatever it may state, for China, it is a bipolar world in which it is in the ascendant.

Quick Reads

View AllThe army parade and Xi Jinping’s speech have attracted worldwide attention. In India, some analysts have felt that they mark the beginning of a new world order. These analysts have also been influenced by the domestic and external chaos being brought about by US President Donald Trump’s persona and policies. Naturally the inconsistencies and ever-changing positions adopted by Trump, especially in his second term, are impacting US power and influence and its capacity to coherently project them. This is in contrast to the implacable and singular-mindedness with which Xi Jinping is taking China ahead.

Current international developments are, therefore, giving rise to important geopolitical and geostrategic issues concerning the future of the current world order. However, the issue of the future of the present world order requires careful thought. There is a need to avoid knee-jerk conclusions. An attempt will be made in the following paragraphs to briefly examine whether China is fundamentally challenging the existing world order or, while accepting its basic postulates, is trying to replace the US as the world’s pre-eminent power. There is therefore a need to distinguish between world order and the major powers which jockey for positions within it.

The existing world order was established in 1945 by the victors of the Second World War. That war ravaged Europe’s colonial powers, including Britain and France. They were immeasurably weakened. The largest colony, India, was waging a great struggle for freedom and national regeneration. Its freedom in 1947 stirred other colonised peoples. The era of decolonisation had begun, and the pre-war colonial order was no longer sustainable.

The US emerged as the strongest power from the war. It decided that it would shun isolationist tendencies and lead the way to form a new world order that would rest on the principles of respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all states and their notional equality. These concepts were projected to underpin the new world order, and the United Nations Organisation was set up to be its bulwark.

However, the war’s victors ensured that their national interests would remain secure in the new order. The mechanism to achieve this purpose was the creation of a UN Security Council, which was vested with the authority to maintain international peace and security. Thus, the US, Britain, France, the Soviet Union and China became a select and dominant group. China’s inclusion was strange because it did not play a real part in defeating the Axis powers.

These states arrogated to themselves permanent membership of the UNSC and also the right to veto any of its decisions without assigning any reasons. The implication was that the UNSC would, above all, serve the geostrategic interests of the victors. In the past 80 years the world has been transformed; the power and influence of countries has changed, but the permanent members have really been unwilling to give up their privileges. Hence, the UNSC, one of the key components of world order, has not been able to function objectively or effectively.

The impairment of the UNSC began early. That came about with the rise of the Soviet Union beginning in the late 1940s and the division of Europe into the Western and Soviet blocs. They became locked in a worldwide ideological struggle which continued for over four decades. This period, known as the Cold War, witnessed the very powers which were responsible for the maintenance of global peace and security breaking the principles of the world order they had themselves established. The Cold War ended in December 1991 with the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The US had won, and some US analysts exultingly, if indirectly, declared that an era of permanent US supremacy had dawned. But the law of unknown consequences caught up with them.

Emphasising the US-China relations, the 1970s saw remarkable progress in bilateral ties. President Richard Nixon was obsessed with transforming the US’s ties with the People’s Republic. He opened up with Beijing. As part of this process, he accepted that Communist China would take the place of Taiwan in the UNSC. Other UN member states had viewed the inclusion of rump China as a P5 member as unnatural, and therefore they did not object. In October 1971 Communist China thus became a P5 member with all its privileges.

In 1978, China changed course under Deng Xiaoping, and with that, gradually but with ever-increasing speed, began an inexorable rise, though following Deng’s advice, it did not advertise its growing strength.

Ironically the US, through its companies and also its government, contributed to building China as the world’s major manufacturing country and also to its becoming a science and technology power. The latter development shook the US. Perhaps its first demonstration came when China became the first country to develop and push the world to accept its 5G communication technology.

Xi Jinping became China’s president in 2013. He soon made it clear that China’s time had come. His aim was to build a constituency of aligned countries. His chosen instrument to do so was the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Through the BRI, China created critical infrastructure in select countries which would also serve its strategic purposes. The BRI is inherently exploitative and ignores the sovereignty of states, but it has been adopted by countries which are short of capital.

The flagship BRI venture is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (Cpec), which has recently entered its second phase. The Cpec involves the development of the Gwadar Port, which poses a strategic challenge to India. Xi Jinping is increasing Chinese military strength and its scientific and technological prowess at a frenetic pace. This indicates that Xi Jinping is enhancing Chinese power on a comprehensive basis. His position in China is secure, and he is challenging US pre-eminence. However, China has a way to go before it can surpass the US.

China has given no indication that it is not willing to adhere to the present world order. Indeed, as noted, in his address to the parade, Xi made points which are in principle in accordance with the present world order. In the ‘Xi Jinping Thought’, also, the 13th of the 14 commitment states is “Establish a common destiny between the Chinese people and other peoples around the world with a ‘peaceful international environment.”

While this is so in theory, in practice China has not hesitated to disregard the decisions of international tribunals, such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), when they have gone against it. Besides, it has shown scant respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of states when these have come in the way of its interests. It says that it does not interfere in the internal affairs of states or their political and developmental models, but in the case of Pakistan, it has always given preference to the army over the politicians—as this writer noted—in his last article carried on Firstpost.

The fact is that China, in behaving, thus, is doing nothing different from the way other great powers have conducted themselves after the present world order was ushered in after the Second World War. Hence, it is not so much concerned with changing world order as with the accretion of its power. That will enable it to maintain that it is keeping to the rules-based order but flout it whenever its interests so demand.

If and when China becomes the globe’s pre-eminent power, it will become more assertive and try to change the foundations of the present world order. But till then it will continue to pay lip service to the rules-based order.

The writer is a former Indian diplomat who served as India’s Ambassador to Afghanistan and Myanmar, and as secretary, the Ministry of External Affairs. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)