For those of us who have been wondering what has happened to Bengali cinema after Rituparno Ghosh , there is finally an inheritor of his illustrious legacy. Not that Aditya Vikram Sengupta’s style of cinematrics resembles Rituparno’s in any detail. Where the two meet is their deep fulfilling understanding of what the city of Kolkata, throbbing to Durga Puja’s festivities and trance dancing to Rabindranath Tagore’s poetry and music, means to the Bengali.

For the great Bengali celluloid creators—and make no mistake, Aditya is one of them—the City Of Joy has constantly been a source of nurturing and inspiration. Satyajit Ray ’s Mahanagar. Mrinal Sen’s Pratidwandi, Ritwik Ghatak’s Nagrik, Aparna Sen ’s 36 Chowringhee Lane and Rituparno Ghosh’s Dosar were, in their own unique way, homages to Kolkata.

To nail down Once Upon A Time In Calcutta as a tribute to Kolkata is to my mind, facile. This motion picture masterpiece is so much more. Delicate in its threading of emotions and yet so strong and powerful in the storytelling, energized by characters that are weak but redemptive, this is a film that cannot be fully appreciated in one viewing. I have seen it twice on two consecutive nights and I still fear I’ve missed out certain things.

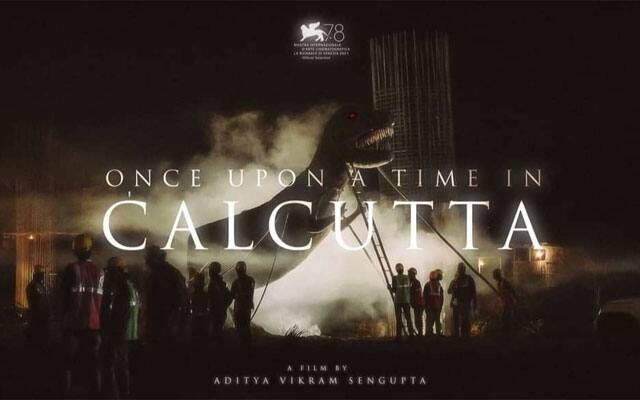

[caption id=“attachment_10981891” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

The poster of Once Upon A Time In Calcutta[/caption]

The poster of Once Upon A Time In Calcutta[/caption]

If you’ve seen Aditya Vikram Sengupta’s debut film Asha Jaoar Majhe, you would know how eloquently he uses silences to convey the anguish of characters that want more from life than mere survival. But ultimately settle for just that. Ela , the memorable heroine (far more memorable than the way she is played) of Once Upon A Time In Calcutta, is grieving when we first meet her, for the loss of her only child, a daughter .

Her husband Shishir (Satrajit Sarkar) is grieving too, though in his own way. He busies himself with his dogs. It is very clear that their shared bereavement has destroyed their marriage. Ela occupies her time drinking and planning an escape from her crumbling home. In fact her concentration on getting to a better life is so relentless that at some point in her social climbing, using one man after another as her ladder, we begin to suspect that the bereavement is no longer the catalyst for her motives. It is something far less honourable. Far more materialistic.

Impact Shorts

More Shorts[caption id=“attachment_10981901” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

A still from Once Upon A Time In Calcutta[/caption]

A still from Once Upon A Time In Calcutta[/caption]

Ela’s fascinating and patently dishonorable journey is immune to all judgement. She is what she is. Although Ela negotiates her demons in questionable ways she never ceases to be en enigma even to herself and to the men who desire her. The role needed the emotional velocity of Roopa Ganguly. It gets Sreelekha Mitra, who most assuredly brings plenty of emotional heft to her character. But at key points I found her holding back. I felt cheated.

The men in Ela’s life are forgettably blasé. They lie, they covet, they lust and they finally move on. There is one male character here whom I felt deeply for, a young struggling bread earner named Raja(Shayak Roy), who is exactly what circumstances make him. At times, he is a financial pimp. But then suddenly his conscience surfaces at unexpected moments.

Once Upon A Time In Calcutta implants the city’s landscape with landmines of dangerous and broken promises. At first, Ela is happy getting her luxuries from her men rather than forcing her stepbrother to give her her share of the ancestral property. But then, life brings her moral scale down to the ground. She is ready to go to any lengths to claim her rights. This is what life does to all of us. Dare we judge others for frailties that we accept in ourselves?

This is a film of endless shapes. The characters change contours in accordance with circumstances. It is not enough to say they are opportunists. There is more at play here than routine acts of desperation. Writer-director Aditya Vikram Sengupta visits the Calcutta that he knows, in search of characters thst desperately want to escape their stifling surroundings. Variations on Tagore’s poetry play incessantly in the background reminding us that subversion of art is inevitable in a fractured society.

Luckily, Once Upon A Time In Calcutta escapes its subversive destiny. It stands tall and stately casting a long shadow on a city and its undefeated people. Turkish director of photography, Gokhan Tiryaki captures the tragic disintegration of values through the city’s relics: broken flyover, broken homes, broken dreams.

Malayalam Cinema Gets A New Dimension With Mahaveeryar

We have seen nothing like writer-director Abrid Shine’s Mahaveeryar before. Absurdist cinema has a very brief history in India. There was Kundan Shah’s grossly overrated Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron. Now there is Mahaveeryar, where one of Malayalam cinema’s biggest superstars Nivin Pauly turns absurdly ascetic to bring out the ageless hypocrisy that governs the uneasy merger of politics and religion in our country.

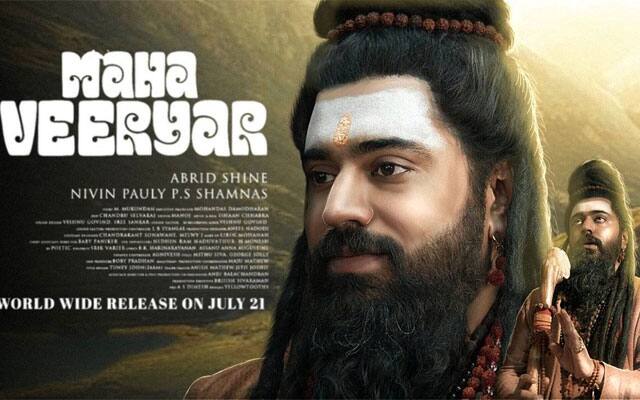

[caption id=“attachment_10981931” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

A still from the film Mahaveeryar[/caption]

A still from the film Mahaveeryar[/caption]

Be warned. The wonderful Nivin Pauly is not the central character of Mahaveeryar. In spite of being the producer, he takes the backseat on screen, appearing in all his saffroned bovine glory as a mixture of a catalyst and a sutradhaar during a court case that would qualify as contempt of court if only it were not so scathingly real.

As an indictment of political oppression, Mahaveeryar requires deep levels of probing and excavation by the audience before we reach the core truth of the proceedings. For all its surface breeziness, this is not an easy film to watch. Mahaveeryar is a dark disembodied parable on the politics of religion. Superstition is not only a bane here. It is the governing factor as the 18th century king Rudra Mahaveera Ugrasena Maharaj (Lal, brilliantly bombastic) orders his minister Veerabhadran (Asif Ali, controlled, compelling) to fetch him the most beautiful woman in the village to cure his perpetual hiccup.

A word on the hiccup: it is no ordinary hiccup. What it signifies is the entire spectrum of politics in the country over the centuries. Lal, the actor who plays the hiccuping King, carries on his shoulder the boulder of absurd and absolute power. He is not cruel to his subjects. But he is not kind eithe. If he treats women (and men) as objects of his convenience, he’s not to be blamed. It is the arrogant self importance we have nurtured in our leaders from time immemorial.

[caption id=“attachment_10981951” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Mahaveeryar movie poster[/caption]

Mahaveeryar movie poster[/caption]

Once the quicksand plot moves into the courtroom, the absurdities multiply. Devyani (Shani Shrivastava) must cure the King’s hiccup, no matter what it takes. Writer-director Abrid Shrine leans into the dynamics of political oppression by making an example out of Devyani. She will shed tears for the King as they are required to cure- His Highness’ hiccups. If not, she will be given the treatment that all non-compliant citizens are given by the State.

Mahaveeryar is a film that breaks all the rules of structured storytelling. It shifts from one time dimension to another without demarcations. It transports the tyranny of 18th century dynastic rule to a present-day court session where the presiding judge (Siddiqui) quickly discards all pretense of fair play and turns into a kind of ghoulish goblin. While the Judge gets progressively aggressive and offensive, the film opens up vistas of unspoken horror that is secreted under the courtroom façade.

The backstage babble includes a cop who is asked by the Judge to count the 24,000 rupees worth of alimony in coins that a man has brought to court for his separated wife. It is a ferociously farcical world of absurd allegorical implications rendered beautifully, subverted by the deeply articulate cinematography of Selvaraj Chandru and the mordant sagacious editing that fluently merges 18th century politics into present day reality .

Like it or hate it, Mahaveeryar can’t leave you indifferent.

Emmanuelle Bercot’s French film Peaceful (French Title De Bon Vivant) was premiered at the Cannes film festival in 2021. It is a rare heartbreaking film about the acceptance of mortality done in a tone that is constantly compassionate and never schmaltzy. Benoît Magimel, who plays a terminally ill man, one of France’s most accomplished leading men, has hardly had any exposure outside his own country.

Magimel has a very unusual screen presence. That the legendary Catherine Deneuve plays his mother in Peaceful is a stroke of luck for the script and for us, the audience, although let me add, Ms Deneuve doesn’t look anything like Magimel’s mother. Nonetheless, such is the beauty and power of this ode on mortality that I was not looking at the actors. All I could see was their pain and anger as they watch a loved one fade away in front of their eyes, helplessly, silently.

Magimel’s Benjamin is a drama teacher. This inspired vocational thrust gives the narrative ample opportunities to explore the theme of love and death on stage from where with rapid fluidity, the narrative blends into a kind of tangential deeply profound and melancholic meditation on mortality .

There is a rare and precious gentleness at the heart of this film, seldom seen in cinema on dying. The embraces and the sobs are infrequent, hence welcomed. While Denveuve and Magimel are effortlessly brilliant in their assigned roles of pain acceptance and tragedy, I must make a mention of Gabriel Sara, playing the doctor in charge of Magimel’s medicinal journey to the other world. Sara, who is a real-life doctor, exudes Santa Claus vibes, soft-spoken and attentive, fully alert to the pain all around that he must negotiate.

Where the film slips up somewhat is in portraying the hospital in a utopian bubble. Only the rich and the privileged can die in such splendour. Peaceful doesn’t pretend to be a realistic depiction of disease and death. It is more about finding one’s core during a crisis. There is no room for lectures and homilies. No one is making a statement here. They are just too busy coping with the crisis to look sideways.

I especially liked the side plot about Benjamin’s son, who is in a dilemma of his own. Should he meet a father whom he has never known, now when the father is dying? There are no easy solutions to the crisis on hand. There are no tears to be shed in this profoundly sentimental journey into the darkness that takes us from this world into….God knows where! If we only knew. This not-knowing makes Benjamin’s journey unbearably arduous and yet magnificently beautiful.

Very rarely does a conversational film with very little movement and almost no dramatic shifts of tone and ambience, have the devastating effect of debutant director Fran Kranz’s Mass, a minimalist drama with just four characters who meet after after an unspeakable tragedy.

There is not much here to rely on except the powerful quartet of actors. For about thirty minutes into the playing time, we are left to grope in the dark as to what troubles these two couples and why are they meeting in the backroom of a church in such a dirge-like environment? What has happened? The feeling of dread hangs overhead in every frame.

What are these four aging souls looking for? Why do they look so devastated? It is with gradually growing horror that we realize what has brought these people into a hopefully healing huddle: the son of one of the couples was a mass murderer, and one of his victims was the son of the other couple.

How do two such stricken snuffed-out people meet without clashing violently? Why don’t they kill each other? Or themselves, for that matter? How have they managed to stay sane after such a brutal tragedy? In Mass, the four actors who play the grieving parents provide all the answers to every question that crops up, as we watch the director give shape through a tormented flow of accusatory words to feelings buried too deep for tears.

As the long-suppressed grievances bubble to the surface, the narration remains miraculously calm. “Let them sort out their differences. Let us keep out of it,” writer-director Fran Kranz seems to suggest. We copy.

It is a no-win situation: the more the two couples converse ,the less the chances of a reconciliation. How do you shake hands with the parents of the boy who brutally killed your son? How does the couple whose son mowed down dozens of his friends in school live to cope with the enormity of their loss?

Watch the faces, the body language and the defeated demeanour of Martha Plimpton and Jason Isaacs, playing the murdered boy’s grieving parents, and Anne Dowd, so well endowed with the acting chops (sorry, couldn’t resist that) and her strangely stoic husband, played by Reed Birney…they play the four traumatized parents as the living dead. Nothing will ever be the same for them.

No, time won’t heal their gaping wounds. You know that’s just a cartful of hokum. Nothing mends a heart of the one so bereaved. But at least at the end of this talkative masterpiece, a dialogue has started.

I like how writer-director Fran Kranz has pitched the grief towards the two women while the men remain in the shadows, at least one of them is marginalized. The other grieving father, Jason Isaacs, is a portrait of unfathomable sorrow. But it is Martha Plimpton, whose imploding rage fills up the frames with signs and messages of untold pain. Plimpton is just bang-on. So is Anne Dowd, though I found her fund of expressions of bewildered grief a little restricted, unlike Plimpton, who just lets it all hang out in shattering motions of suppressed emotions.

At a time when random mass killings are all around us, Mass is a relevant and stunning work of emotive art, bringing out the various facets of human failing and feeling in the same line of vision. This film is not judging anyone: not the perpetrators, not the victims, not their parents. Mass is a dispassionate, masterful medication on mayhem and melancholy.

Subhash K Jha is a Patna-based film critic who has been writing about Bollywood for long enough to know the industry inside out. He tweets at @SubhashK_Jha. Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram .

Subhash K Jha is a Patna-based journalist. He's been writing about Bollywood for long enough to know the industry inside out.

)