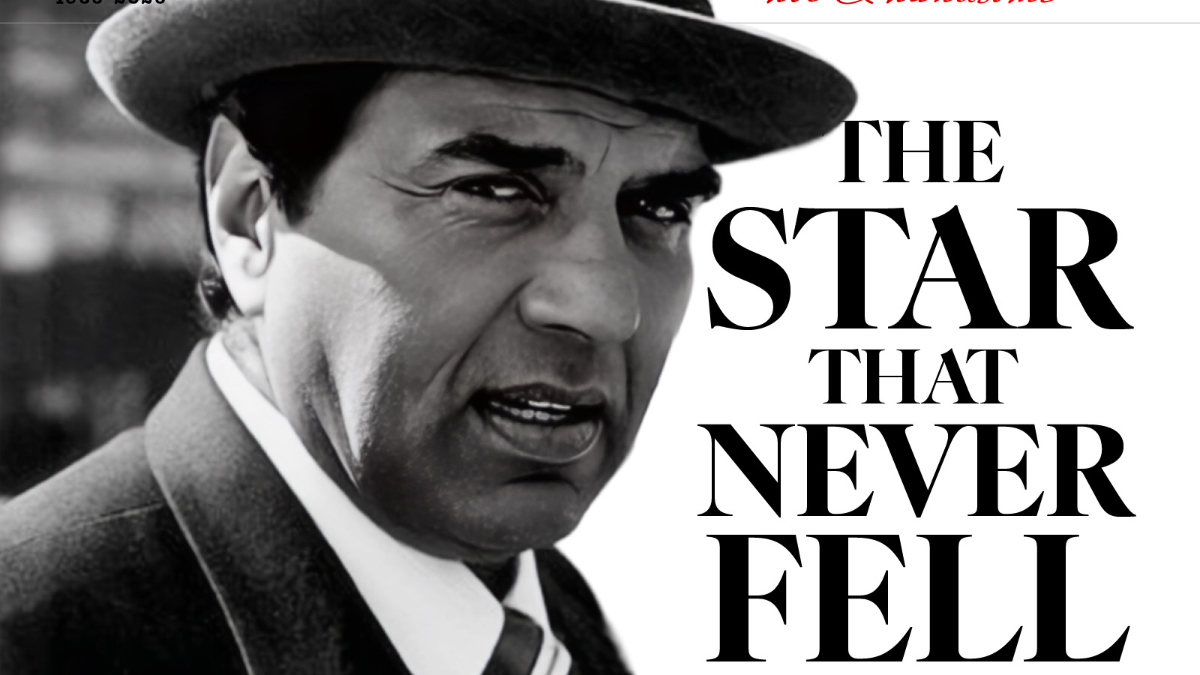

There are stars who belong to their time, and then there are those rare figures who gently bend time around themselves, shaping how an entire nation imagines strength, yearning, and the ineffable magic of the cinema. Dharmendra’s life and career are not just the story of a beloved actor—they form a chronicle of how India negotiated masculinity, grace, and heroism across six tumultuous decades, and how one man consistently stayed ahead of a culture that often did not know what to do with him.

When he arrived on the horizon in the late 1950s, Hindi cinema was still in thrall to the romantic trinity of Dilip Kumar, Dev Anand, and Raj Kapoor. The leading man of that era was expected to be poetic, introspective, slightly fragile—a figure whose emotional vulnerability was more vital than his physicality. A broad-shouldered, well-built hero belonged, at least according to the industry’s orthodoxy, to another category altogether: the swashbuckling daredevil in the Prithviraj Kapoor or Jairaj mould, or the strongman archetype that would soon be monopolised by Dara Singh.

Dharmendra confounded those expectations before they could harden into dogma. Unlike the second-generation aspirants of the time who consciously borrowed from Dilip, Dev, or Raj, Dharmendra entered without any inherited grammar or lineage. He won Filmfare’s new talent contest, but his break didn’t come easy. He debuted in Arjun Hingorani’s Dil Bhi Tera Hum Bhi Tere (1960), but success came with Anpadh (1962). He was, in a very real sense, Hindi cinema’s first breakaway leading man—a star born without resemblance, without borrowing, without the comfort of imitation. His early work under Bimal Roy only deepened this rupture.

Roy, the quiet poet of Hindi realism, saw in Dharmendra a gentleness and dignity that did not require diminution of strength. In Bandini (1963) and Anupama (1966), Dharmendra played men defined not by physical force but by emotional intelligence. He stood tall, but he did not loom. He carried a presence but never imposed it. In an industry unsure whether a handsome, athletic man could also be tender, he simply showed that he could—without fuss, without self-consciousness.

Quick Reads

View AllThe inflection point that forever shifted how India viewed him—and how India viewed the hero—came in 1966 with Phool Aur Patthar. Popular memory clings to the iconic shirtless silhouette, but the deeper truth lies in how Dharmendra played the character: a man hardened by circumstance yet yearning for connection, a tough exterior holding a bruised, almost embarrassed vulnerability. This was not just a breakthrough for him; it was a breakthrough for Hindi cinema. For the first time, the audience saw a leading man who combined a distinctly Indian masculinity with an almost literary sensitivity—an archetype that did not previously exist in our cinematic tradition.

But the road to consecration was never straightforward for Dharmendra. History remembers the great star coronations—Rajesh Khanna’s meteoric rise in 1969 and Amitabh Bachchan’s epochal ascendancy in the mid-1970s. Fewer remember that just before both those ruptures, the industry was whispering another name. Dharmendra’s successes in the mid-1960s covered an array of genres—Shikhar Haqeeqat, Mamta, Devar, Aankhen, and Aaye Din Bahar Ke. Dharmendra had three separate windows—1969, 1973, and the mid-1980s—when the mantle seemed poised to fall on him. Each time, the industry turned away at the very moment it should have embraced him.

His self-produced masterpiece Satyakam was released in the same year that Khanna exploded with Aradhana. Dharmendra delivered a staggering performance—arguably the finest of his career—but the zeitgeist had already chosen its new crown prince. Khanna became a phenomenon; Dharmendra became a footnote of that transition. It was not a failure of craft or popularity—it was simply the peculiar, almost karmic timing of his career.

When Rajesh Khanna’s aura began to fade in the early 1970s, Dharmendra was one of the few who held his line. In 1973 alone, he had a run most stars would kill for: Blackmail, Jugnu, Jheel Ke Us Paar, Kahani Kismat Ki, Loafer, Jwar Bhata, and Yaadon Ki Baarat—all superhits. Yet the industry was too busy writing Rajesh Khanna’s obituary and Amitabh Bachchan’s origin myth to notice. The year that should have belonged to Dharmendra quietly slipped into the margins as the “Angry Young Man” seized the public imagination.

Even in 1975—the year of Sholay, Pratigya, and Chupke Chupke—his performances were overshadowed by the narrative of Bachchan’s domination. In Sholay, Veeru is the heart of the film’s humour and much of its emotional current; in Chupke Chupke, Dharmendra executed one of the most technically difficult comic performances in Hindi cinema. But in a season of coronations, recognition rarely flows evenly. And yet, he endured. Quietly, confidently, without rancour. Dharmendra never chased the number-one tag, but ironically, his ability to remain undiminished despite not receiving it is what makes him singular. He is Indian cinema’s great “lost king”—the superstar who stood beside emperors without ever needing their thrones.

This “in-betweenness” is not a flaw in his legacy; it is his legacy. Dharmendra is the finest example of how a star can remain beloved without being canonised, how relevance can outlast rhetoric, and how longevity can be a form of triumph. Across five decades, he excelled in every genre. His dramatic range produced films like Satyakam and Khamoshi, works of deep emotional resonance. His action persona drew audiences from the late 1960s well into the bombastic 1980s, where he delivered hit after hit even as the industry ignored the magnitude of his box-office power. His romantic screen presence—soft, unforced, and endlessly genuine—remains unmatched.

But perhaps his greatest, most surprising gift was comedy. Chupke Chupke alone is enough to elevate him to the upper echelons of comic performers, but see him in Dillagi and you know just how confident and comfortable he is—there is a scene where he drapes himself in a sari as his clothes dry and sips tea with Hema Malini. Dharmendra never played comedy as an escape from his persona—he played it through his persona. His humour was rooted in intelligence, rhythm, and the self-awareness of a man fully comfortable with the absurdities of stardom. Long before the Khans mastered tonal fluidity, Dharmendra had already demonstrated that a leading man could move from drama to comedy to romance without losing authenticity.

Through all this, something subtler—and perhaps more profound—was happening. Dharmendra was becoming a mirror for Indian society’s conflicted view of masculinity. He projected strength without aggression, desire without domination, and charm without arrogance. He showed that a man could be physically imposing and emotionally open without betraying either side. This, in retrospect, is his quiet revolution.

At a time when heroes were expected to either brood or preen, Dharmendra offered an Indian masculinity that was instinctively egalitarian—firm yet gentle, dignified yet playful. The nation embraced him because he made heroism feel human.

The 1980s brought yet another moment when fate seemed ready to give him the crown. With Ghulami and Hukumat, followed by a barrage of hits, Dharmendra delivered box-office numbers that dwarfed many contemporaries. Yet again, the industry looked elsewhere—towards new faces and rising trends. And yet again, Dharmendra refused to break stride. His sustained success in an era of churn reveals an industrial truth: he was the only star who mattered in every decade of his working life, even when the narrative insisted otherwise.

By the 1990s, when the industry was recalibrating around the youthful softness of the Khans, Dharmendra gracefully stepped back, choosing to shift focus to production and to his sons. And then, in one of those poetic turns that cinema occasionally allows, he returned unexpectedly—not with bombast, but with wisdom. His performances in Life in a Metro and Johnny Gaddaar reminded audiences of a forgotten truth: he had always been a superb actor, capable of nuance that could speak louder than any monologue.

His cameo in Johnny Gaddaar in particular—quiet, dangerous, weary—revealed the depth of an artist who had lived inside cinema for half a century without ever becoming cynical about it. And Yamla Pagla Deewana, and Apne buoyed by audience affection across generations, testified to his undimmed charm. Even towards the end of his life, Dharmendra remained fiercely loved. He was not merely remembered; he was felt. His presence carried the continuity of an India that has changed beyond recognition. Watching him on screen was like opening a window to a version of ourselves that was perhaps kinder, more trusting, and less consumed by irony.

Dharmendra worked with generations of actors and filmmakers and never showed signs of stopping. His penultimate film, Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani, introduced him to a new generation, and the return of form of his younger son Bobby with OTT and Animal, along with elder son Sunny’s newfound third innings, showed sparks of a reunion of the three Deols. His final film, Ikkis, where he plays Brigadier ML Khetarpal, the father of the young PVC recipient Second Lieutenant Arun Khetarpal, features him opposite Agastya Nanda, the grandson of Amitabh Bachchan.

What, then, is Dharmendra’s legacy?

It lies in the fact that he survived without bitterness in an industry that often rewarded spectacle over sincerity. It lies in the way audiences across five decades instinctively reached for him—not for his brawn, not for his star power, but for the quiet humanity that underlined everything he did.

He is the only major star in the history of Hindi cinema to have been simultaneously embraced across the eras of Dilip-Dev-Raj, Rajendra-Shammi-Manoj, Rajesh Khanna, Amitabh Bachchan, and the Khans—without ever being overshadowed completely, without ever being fully acknowledged either.

That paradox is what makes him timeless. He leaves behind not just films, but a feeling—a softening of the heart, a reminder that strength need not shout, that heroism need not announce itself.

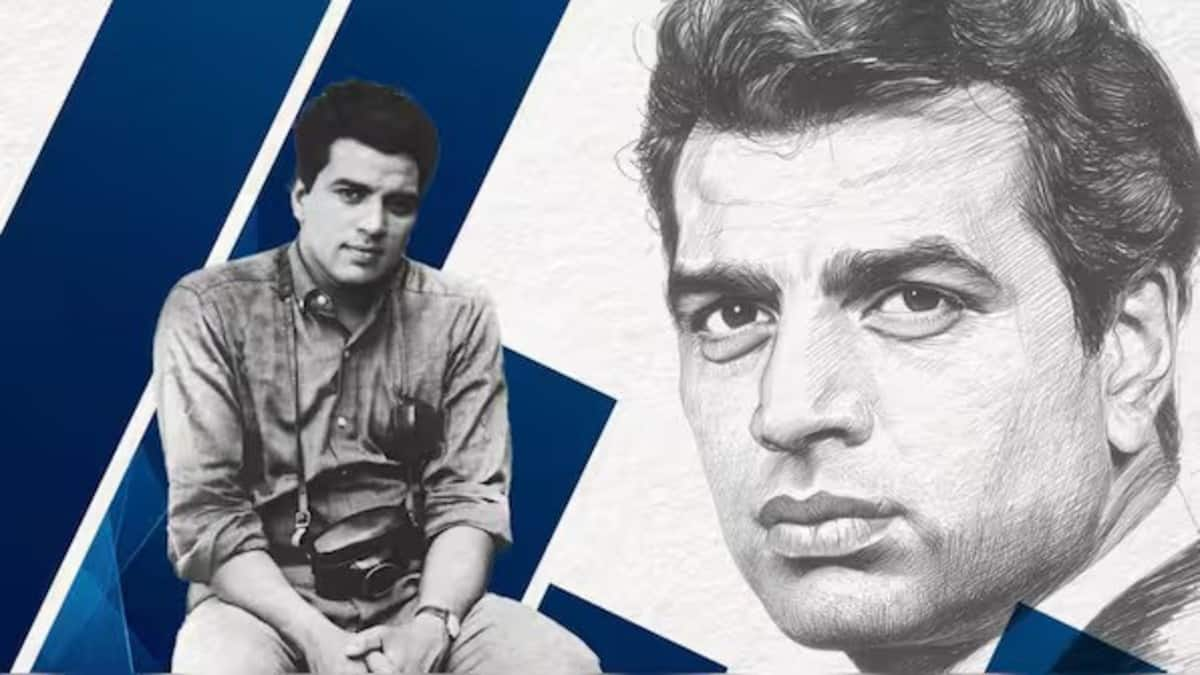

When I began working on a book about him in 2016, I met him several times. Each meeting felt like stepping into a gentler world—he was warm, affectionate, patient, and always ready with a smile. He would say, almost with childlike disbelief, ‘Yaar, I still have so much to do… why a book?’ and then launch into a cascade of stories that spanned hours and eras. His humility, his sweetness, and his eagerness to share—these were reminders that the man behind the stardom was far more radiant than the spotlight ever allowed.

Dharmendra did not need the title of “superstar”. The word is too small, too limiting, too dependent on a hierarchy he never cared to participate in. He was something more elemental—an actor who embodied the modern Indian hero before India had fully articulated what it wanted from its heroes. He was laughter, gentleness, mischief, longing, courage, and warmth. He was the cinema we grew up with and the cinema we still look back to when the present becomes too sharp.

Dharmendra did not pass away at 89. Because for millions it’s practically impossible to imagine a world without Dharam ji… He simply walked from the light into the legend that was always waiting for him.

(The writer is a film historian. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)