In her heyday between the late 1930s and early 1950s, Hedy Lamarr — a Hollywood star celebrated for her breathtaking beauty — appeared in over two dozen films. Though occasionally admired for her craft, praise for her looks invariably drowned everything else out. In the process, her gifts as an inventor were almost entirely ignored. She shared with composer George Antheil a patent issued in 1942 for a technological system still used in secure military communications.

Lamarr believed people failed to recognise her intellect because they were blinded by her beauty. In his book Hedy’s Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Richard Rhodes writes how being labelled “the most beautiful woman in the world” — as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s publicity machine insisted — “annoyed Hedy deeply”, because “few people saw beyond her beauty to her intelligence”. Lamarr famously remarked, with bitter wit, “Any girl can be glamorous. All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.” In her 1966 memoir Ecstasy and Me, she lamented, “My face has been my misfortune… a mask I cannot remove. I curse it.”

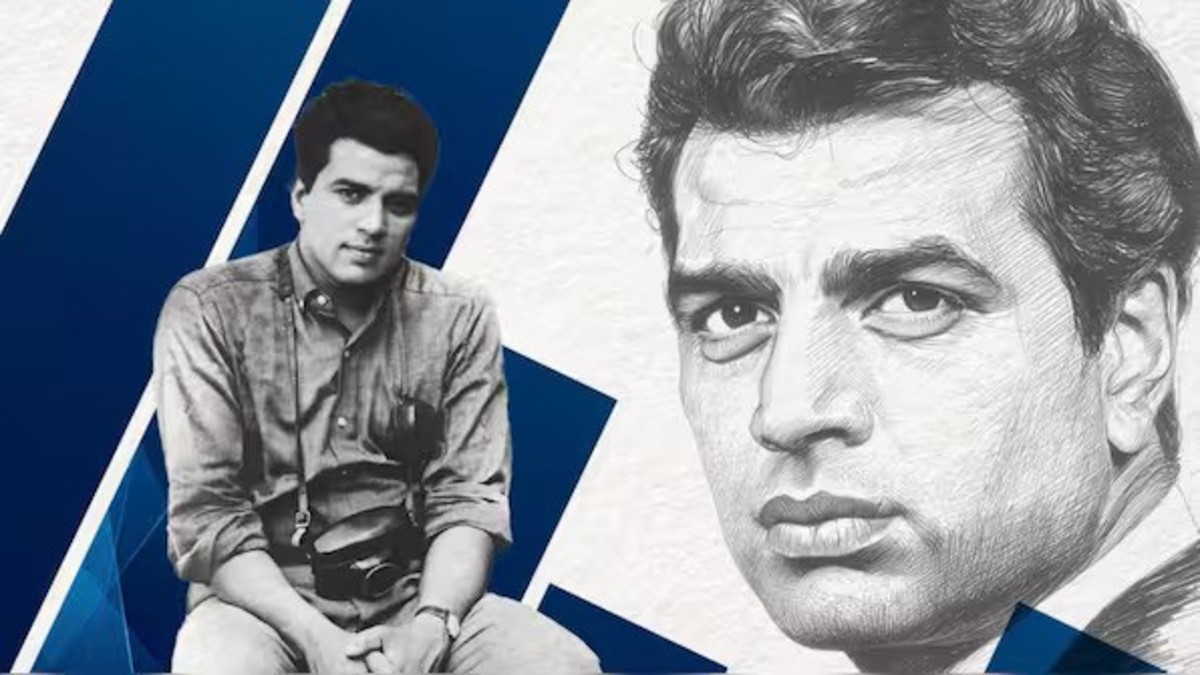

In Hindi cinema, Dharmendra faced a similar Lamarr-ian dilemma. His Greek-god looks overshadowed his acting prowess. Although discovered in a Filmfare talent contest in 1961 by Bimal Roy and Guru Dutt, and after appearing in nearly 300 films, Dharmendra never won a single Filmfare Best Actor award. He received a Lifetime Achievement award in 1997, but the magazine never deemed any single performance worthy of the iconic “Lady in Black”— not even his unforgettable Veeru, Parimal or Satyapriya.

As film historian Gautam Chintamani writes in an article in 2015: “One of the most enduring mysteries of Hindi cinema is the manner in which it chose to sideline an actor and a superstar such as Dharmendra, who, unlike many of his contemporaries, could don a dhoti with the same ease with which he could sport a Roman Toga, he could be smouldering in a tuxedo and set a million hearts ablaze in a bundi and could make you laugh, sigh, and cry without making a big deal of it.”

Quick Reads

View AllDharmendra may not have won the number of awards he deserved or may not have got the kind of accolades he should have, but he definitely ruled the hearts of the masses. He remained the most popular star of his time, and even during the superstardom of first Rajesh Khanna and later Amitabh Bachchan, if there was one actor who held his own, it was Dharmendra.

Born in a Punjab village to a school-teacher father who hoped he would become a professor, Dharmendra later said that his role as a professor in Chupke Chupke was a tribute to that wish. When he excitedly screened the film for his father, the latter affectionately responded that this wasn’t quite the kind of professor he had in mind.

He chose acting after watching Dilip Kumar in Shaheed at Minerva cinema in Ludhiana while in Class VIII. The film left a lasting impact, turning cinema into his lifelong passion. Later in Bombay (now Mumbai), disillusioned and ready to leave for a job in Delhi, he was held back by friend Manoj Kumar, who promised to support him for two months. The rest, as they say, is history.

Across a long career, Dharmendra played diverse roles — from Anupama and Satyakam to Sholay and Chupke Chupke. Vijayakar tells a story to explain how Dharmandra could play such diverse roles so effortlessly. As it happened, Guru Dutt was suddenly called to attend a court case just before the finale of the Filmfare talent contest. Dharmendra was selected among six others. Abrar Alvi, Dutt’s friend and writer, was told to conduct the test with instructions to “check the contestants’ faces, profiles and dialogue delivery from the filmmaker”. When Dutt returned, Alvi informed him about Dharmendra, “who had a crew cut, while everyone else had long hair, modelled broadly on Dev Anand’s style”. When Dutt asked him who he was like in terms of acting style, Alvi said matter-of-factly, “Nobody! He is himself, has no pretensions, no set notions. The boy seems an original and it might be possible to mould him and develop his personality.”

That originality made him unique. It explains how he could effortlessly play the dhoti-clad Satyapriya in Satyakam and the bare-chested Shaka in Phool Aur Patthar. He was the first superstar unbound by image — and yet he never came to be associated with great acting —something a Sanjeev Kumar or Dilip Kumar would. His looks, maybe, became his curse as an actor. And then the 1980s happened, when cinema’s shift towards action trapped him in the “He-Man” persona. This new image just got attached to him so deeply that his other characters faded away.

Why did it happen?

The answer, probably, lies with the very persona of the actor. If the ever-simpleton Jat in Dharmendra endeared him to the masses, this very happy-go-lucky persona may also have trapped him within itself. Till the time the industry was dominated by cerebral filmmakers, mostly from Bengal, such as Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Bimal Roy, Pramod Chakravorty and Shakti Samanta, he gave rousing performances, but when the nature of Hindi cinema changed with the arrival of new directors, things turned awry for him. Instead of steering the industry, he went with its flow, which at the time favoured B-grade action films.

But what he never lost was his connection with the masses. He remained rooted, humble and innocent. That is what kept him beloved. Dharmendra is arguably Hindi cinema’s most mass-appeal star — the aam aadmi’s superstar, without question.

(Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)