Shortly after Dr RC Majumdar’s book on the history of Bengal viz. Bangla-Desher Itihas Vol-4 (in Bengali) was published, his former student and publisher Suresh Chandra Das received a handwritten letter (in Bengali) from Justice Phani Bhushan Chakravartti (1898-1981), the former Chief Justice of Calcutta High Court (1952-58), who had also served as the Acting Governor of West Bengal between 8 August and November 3, 1956. While complimenting the publisher for bringing out a masterly piece, Justice Chakravartti (Retd) narrated an incident that had never been in the public domain before. The retired jurist referred to his meeting with former British Prime Minister Clement Richard Attlee (1883-1967), when the latter sojourned at Raj Bhawan (Governor’s House) of Calcutta (now Kolkata), on an Indian tour in 1956. It was during Attlee’s two-day stay at Raj Bhawan that Justice Chakravartti reportedly had long discussions with the former British Prime Minister on various issues including why the British chose to grant India independence in 1947. It is needless to remind that Attlee was the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the Transfer of Power. The Labour Party had stormed into power in the British general elections of 5 July, 1945. Justice Chakravartti’s contention was that the Quit India Movement (1942) had fizzled out within a few months. If the British could weather that movement, in the midst of World War II, what promoted the British to leave India in a hurry in 1947? Attlee reportedly mentioned a few reasons for that British decision, especially the erosion of loyalty towards the Crown in the Indian armed personnel. He attributed this changed attitude to Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s Azad Hind Fauz (INA). It might be remembered that many soldiers of the British Indian Army, despite swearing loyalty to the King and God, had switched sides to the INA due to patriotic motives. Though the INA was not successful in its mission, the INA trial (Second Red Fort Trial) 1945-46 provoked the nation. The British dare not actually punish the prosecuted officers for fear of mass reprisal. There was mutiny in Royal Indian Navy in February, 1946 inspired by the INA’s example. Towards, the end of their discussion, Justice Chakravartti asked Attlee about the influence of Gandhi on the British decision to leave India. Attlee, we are told, smiled sardonically, and replied, “m-i-ni-mal’ (modulation Justice Chakravartti’s). Dr. Majumdar narrates the incident in his memoirs (in Bengali) Jiboner Smritideepe (P.228-231) and provides a facsimile copy of the letter (attached here). Jiboner Smritideepe (1978), was published when Dr Majumdar was 90 years old. He chose to include this reported incident not in any scholarly work, but in appendix of his memoirs, without any critical remarks. The existence of this letter was known in Bengali literary circle for many years. However, it was General G.D. Bakshi who gave it a forceful national exposure in his book viz. Bose, An Indian Samurai- Netaji and the INA: A Military Assessment (2016). It was subsequently taken up by eminent Netaji research scholars like Anuj Dhar and Chandrachur Ghoshe, who have even fished out photos of Attlee’s visit to Calcutta and meeting with Justice Chakravartti and tweeted them.

II

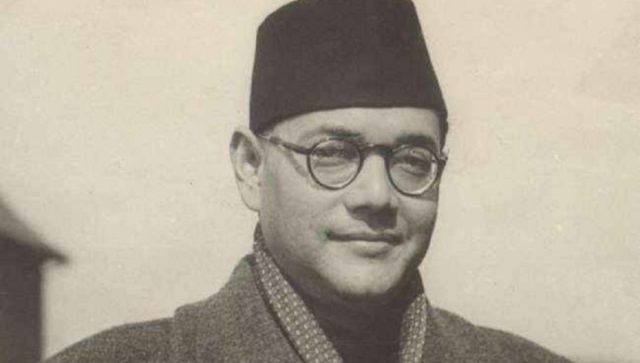

There is certainly no doubt about Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s patriotism, valour and enterprise that brought India within inches of freedom. It is also a fact that political initiative had moved out of the Congress’ hand after the Quit India Movement fizzled out. After the failure of Simla Conference (June, 1945), when the Congress Working Committee met at Poona (Pune) on 14 September, 1945 and after a few days adjourned to Bombay (Mumbai) there were heated discussions on a new line of policy. Maulana Azad, informs that a majority, including Gandhi, held that the Congress must dedicate itself exclusively to constructive work, as there was not much hope was there on political plane (India Wins Freedom, P.141). Maulana Azad, the then Congress president, argued that the party should have confidence in the new Labour Government (led by C R Attlee) in Britain. The party, instead of launching any new movement, should participate in the General Elections promised.

III

The hard fact is that India did not win her freedom through direct and frontal fight unlike the USA in the 18th century, Greece in the 19th century, and Bangladesh in the 20th century. In those countries, the sword that had been unsheathed was not put back into the scabbard until the freedom was won. There was no intermission where the fighting parties sat down and smoked together. However, this happened in India, more than once. Acknowledging this plain fact hurts our self-respect in 21st century, when India is eyeing to be a world power. Thus it must be proven that we ‘booted’ the British out like the Americans did in the 18th century. Even if we can’t prove it, on the basis of available facts, it has to be established that we made the life for British so intolerable and insecure that they realized that discretion is the better part of valour. They allegedly fled by handing the Indians independence in a haste. Thus we link a RIN mutiny in February, 1946 to British leaving in August, 1947 as though they were “mortally terrified”. Did mutineers grant time of 18 months to their military masters anywhere in the world? Did the British leave in hurry, and if so, could that haste be necessarily linked to mutinous tendencies in the armed forces? In this whole scheme of things we are discounting the role of Muslim League, which had begun to foment large scale riots since August, 1946 in order to force the British to concede partition. The British Indian Army behaved in quite a coherent manner down to the day of independence. This was despite the fact that it underwent division on communal basis with Hindu and Sikh personnel opting for India, and Muslims mostly Pakistan. At least there was no crisis of leadership or insubordination at any point of time after February, 1946. Would the British have not granted India independence without Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s military campaign, or its domino effect? The answer lies in considering the long time perspective. The independence of India was not an event, but a process. The Government of India Act, 1919 was aimed at granting India ‘responsible government’ under which direct elections to legislature on territorial basis, though based on extremely limited franchise size, were introduced in India. The narrative was carried forward in the Government of India Act, 1935 (the longest legislation passed by the British Parliament until 2011) under which the Congress could form governments in eight out of the 11 provinces. The question is why were the British introducing constitutional reforms in India, gradually holding over political power to Indians in a structured manner over the decades. The Mughals or Marathas never did the same in their time. Neither did the potentates of princely states, who between them ruled over 45 percent of Indian territory and 25 percent of population of India, initiate any substantial reform. The answer is that the British had the goal of self-government for India before them. Ramsay Macdonald, the then Prime Minister of Britain, while speaking from the Chair at the First Round Table Conference on 12 November, 1930 said: “The declarations made by British Sovereigns and Statesmen from time to time that Great Britain’s work in India was to prepare her for self-government have been plain. If some say that they have been applied with woeful tardiness, I reply that no permanent evolution has seemed to anyone going through it to be anything but tardy”. Should an official speech delivered by a British Prime Minister, at the Round Table Conference, in presence in 89 delegates- 57 from British India, 16 from princely states and 16 from British political parties- have less historical value than what a former Prime Minister of Britain allegedly said in a private conversation? That the British were determined to concede self-government to Indians – months before the INA trial and IRN mutiny- is proven by the statement of Secretary of State in Churchill’s national government viz. Leopold Amery in the House of Commons on June 14, 1945. Amery concludes his speech thus- “His Majesty’s Government feel certain that given the goodwill and a genuine desire to cooperate on all sides, both British and Indian, these proposals can mark a genuine step forward in the collaboration of the British and Indian peoples towards self-government and assert the rightful positions, and strengthen the influence, of India in the counsels of the nation” -Anil Chandra Banerjee (ed), The Making of Indian Constitution 1939-1947 Vol-1 (Documents), P. 95. On the same day in Delhi, Governor General Lord Wavell made a radio broadcast over All India Radio. In fact, taking aid of five and half hours advantage that India enjoyed over the GMT, he could almost synchronize it with Amery’s statement in British Parliament. His opening words were- “I have been authorised by his Majesty’s Government to place before Indian political leaders proposals designed to ease the present political situation and to advance India towards her goal of self-government. These proposals are at the present moment being explained to Parliament by the Secretary of State for India. My intention in this broadcast is to explain to you the proposals, the idea underlying them, and the method by which I hope to put them into effect” (ibid, P.95-96). The statements by Amery and Lord Wavell also disprove the common myth that Winston’s Churchill was absolutely impervious to the idea of conceding India any self-government (independence). However, admittedly, the advent of Labour Government in power only accelerated the process. The Labour Party’s landslide victory in the British general elections of 5 July, 1945 (results declared on 26 July, 1945) was a defining hour. C. R. Attlee took office on 26 July, 1945. Lord Pethick-Lawrence was appointed the new Secretary of State. At that time the War had not concluded in the Asia-Pacific. The British had been able to wrest control of Burma (Myanmar), but Singapore was still under Japanese occupation. It would be interesting to note what C. R. Attlee records in his memoirs As It Happened (1954), which had been completely overlooked in pursuit of ‘minimalist’ view of history. He mentions there Subhas Chandra Bose once in the passing. However, what he says about self-government was more important. “Successive British Governments had declared their intention of giving India full self-government. The end of the war would certainly bring a demand for these promises to be implemented. Furthermore, our allies the American people had very strong views, shared by the Administration, of the evils of imperialism. Much of the criticism of the British rule was very ill-informed but its strength could not be denied…. Prior to the War, I had a long talk with Cripps and Nehru on possible lines of dealing with the problem of Indian self-government and we had sketched out an idea of the constituent assembly to be summoned in order that Indians themselves might decide on their future “(As it Happened, P.180-181). Thus the contention that the British were compelled to give independence to India in 1947, against their plans and wishes, is rather preposterous. On the contrary, those who take a minimalist view, overlook the complexity of independence. It involved settling the communal question, the issue of princely states, and the matter of Constituent Assembly. Had British fled in a huff, it would have resulted in anarchy, comparable to 1857. There was a long-drawn process of Transfer of Power. Between June, 1945 to June, 1947 the British toyed with idea of loose federal constitution for India. When that did not succeed, plan for partition had to be announced in Governor General Lord Mountbatten on 3 June, 1947. The myth that the British left India in haste, perhaps had its origin in Prime Minister Attlee’s statement in House of Commons on 20 February, 1947 that His Majesty’s government would like to hand over power not later than June, 1948. It never meant independence would be given only in June, 1948 and not before. The General Elections were held in India in the winter of 1945-6 as a result of which central legislative assembly, council of states, and provincial councils were re-elected. The results of the elections showed India was a nation divided on communal lines as far as Pakistan demand was concerned. A Constituent Assembly was elected indirectly from the provincial legislative councils. The Constituent Assembly started functioning on 9 December, 1946 though the Muslim League members never joined it. However, it simultaneously proves that the British withdrawal from India occurred in a planned manner rather than in panic as being alleged by some. When the British rule came to an end at the midnight of 14-15 August, 1947 the sovereign power was assumed by the Constituent Assembly that also acted as a unicameral provisional Parliament under a Speaker (GV Mavalankar) in addition to Constitution making body (under the Chairmanship of Dr Rajendra Prasad). Commander-in-Chief General Rob McGregor Lockhart’s address to the Indian Army after independence on 18 October, 1947 praised the army for its remarkable performance during the disorders. “I am proud of you and I want you to convey to your men my pride in their work” (PIB Press Release C-in-C’s Address to Army Officers, October 18, 1947). The last British troop left India was the 1st Battalion of Somerset Light Infantry. They set sail from the Gateway of India in Bombay amidst a resounding farewell. A silent video of the occasion is available in the online archive of British Pathe. The British rule thus came to end in India without bitterness towards former rulers, in sharp contrast to how French rule came to an end in Algeria or Vietnam. The acrimony and horrible carnage that tarnished the independence was as a result of communal riots, not anti-British violence. If the British had fled in panic, there might have been discord between the Army and civilian authorities on the question of withdrawal, which could not have been concealed in public for long. One might remember how Secret Armed Organization (OAS), a rightwing French paramilitary group, had tried to assassinate French President Charles De Gaulle when he signed Evian Accords in March, 1962 granting Algeria independence. The event was famously dramatized in Fredrick Forsyth’s novel The Day of Jackal (1971), later turned into a blockbuster film. Did anything of that sort remotely happen in Britain? “I have never read about people”, observed Nirad C. Chaudhuri (1955), “who have been so happy to lose an empire and so ready to think that the loss is really a great gain. That simply shows that in spite of having created the greatest empire the history has seen, the English people never had any real understanding of empires. Those who have do not lose them in less than two hundred years” (A Passage To England, P.194). Chaudhuri visited England for the first time in 1955. Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose completed the missing aspect in India’s freedom struggle- a national army. His military enterprise filled the Indians and home and abroad with patriotism, pride and spirit of self-reliance. There was hardly any such example in the entire world. However, he himself never conceived of achieving success without support from the Congress at home. His campaign did not succeed directly. Whereas it has its unique place in the history freedom movement, it is improper to see it out of perspective. A reductionist view of history must be eschewed. The writer is author of the book “The Microphone Men: How Orators Created a Modern India” (2019) and an independent researcher based in New Delhi. The views expressed herein are his personal. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views. Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)