French philosopher Albert Camus once asked, “What is a rebel?” And answering his own question, he said: “A man who says no.” When fear is gone, it marks the beginning of the fall of a tyrant. Soon the whole nation says no. And the tyrant falls. China — currently witnessing protests of the scale, intensity and magnitude not seen since the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident — looks edgy but it seems too strong to meet the challenge. Yet, what would keep people interested is the fact that tyrants, historically, look stronger than they actually are. But when the end moment comes they all fall like a pack of cards. Mikhail Gorbachev, Saddam Hussein, Muammar Gaddafi, Hosni Mubarak, et al… the list is long, almost endless. But then, China is different. It is awfully rigid; there is something about China that never changes — its extreme lust for power and insatiable greed for land. Yet, the Dragon knows well when to take out its blood-dipped claws, and how to hide them. It’s this extreme ease of adaptability that has enabled communist China to overnight become a capitalist nation under Deng Xiaoping. And when it senses a flux in the global order, as it did post the 2008 global economic crisis and particularly after the pandemic pandemonium, it takes no time in saying goodbye to Deng’s “hide your strength, bide your time” mantra. Xi Jinping’s China is unapologetically aggressive; it doesn’t shy away from showcasing its blood-dipped claws. Still, there’s a common streak among all tyrants and autocracies that refuses to go away. Just like the proverbial scorpion of an Aesop story that couldn’t stop biting the frog even when it meant drowning in the river — “I could not help it; this is in my nature,” says the scorpion — an autocracy by its very nature is designed to oppress people, to make them bleed, often for no reasons other than the lingering fear not to look weak! Today, as China finds itself in the throes of massive protests, catalysed by Xi’s zero-Covid policies, the same scorpion-like tendency is perceptible. People have taken to the streets across the country to call for an end to ruthless lockdowns and for greater political freedoms. It’s an autocracy’s biggest nightmare and also a dilemma. An autocracy is designed to react violently to any opposition. And if it ever tries to act otherwise, it is presumed to be weak, thus fuelling further protests. Chinese Hare Vs Indian Tortoise China’s incredible growth story since the Deng era has made the world sit up and take notice. There are countless tales of the Chinese hare and its giant strides forward, which simultaneously mocked the Indian tortoise for moving unhurriedly and squandering time on mundane debates and discussions. Their Covid handling, however, has turned the narrative upside down. India, taking cue from its close encounters with Covid-19, has decided to live with the virus. China, quite characteristic to its autocratic nature of governance, is engaged in an intense battle to defeat the virus! No wonder, while the rest of the world, including India, has largely opened up, China has gone in for strict, often inhuman, lockdowns. The biggest problem for China is its failure to course-correct itself. Its authoritarian streak stops it from being flexible. This was the case when it realised the ineffectiveness of China’s indigenous vaccines. As one China watcher observed, the Xi dispensation let national ego trump science. Such is the nature of the autocratic game. The state just can’t be seen to be bending backwards, more so when Xi is busy modelling himself after Mao. This is where the dividend of being a democracy comes in the spotlight. In sharp contrast to China, India’s Covid policy has been flexible and responsive. The Modi government has never been averse to tweaking — and in extreme circumstances, even overturning — its pandemic policy. So, the Indian government first went in for total lockdown when it realised the country didn’t have basic medical infrastructure to deal with a pandemic of this scale. It shut the transport down, but when migrants and labourers started walking back to their homes in towns and villages after state-induced lockdowns took away their jobs in metros and cities, the government ensured they were sent home via public transport. Likewise, when India was devastated by the second Covid wave, the Modi government fast-tracked the immunisation programme. Once it was done, administering the record two million plus jabs, and when the government was confident about the strength of the country’s medical infrastructure, it lifted lockdowns altogether. India decided to live with the virus. So much so that even the mandatory masking was given up. All’s Not Well On Economic Front History might suggest most tyrants appeared invincible till they fell at the first collective punch from protesters. But this doesn’t mean a regime change is on cards in China. It at best can be summed up as a personal setback for Xi Jinping, especially when he, after becoming the President for the record third time, seemed so invincible. Xi’s major challenge remains the economy. China had faced similar protests in 1989, but at that time the country was riding high on Deng’s economic successes. Chinese were ready to forfeit a part of their freedom for the luxuries they foresaw in their lives. But the situation is different today. The Chinese economy hasn’t been doing that well for some time now. Its real estate is in dire straits, and several major companies are shifting bases out of China. In fact, Japan provides economic assistance to its companies looking to move out of the Chinese shores! Though many Chinese watchers would not agree with the following assessment, I seem to lean towards Frank Dikotter’s analysis that China is much weaker economically than it appears from the outside. And its path to economic recovery may not be that easy. The problem is intrinsically rooted in the very nature of communist ethos, governance and economy. As Xiang Songzou, a professor of economics at the People’s University in Beijing and erstwhile deputy director of the People’s Bank of China, stated in an article in AsiaNews in 2019, “Basically China’s economy is all built on speculation, and everything is over-leveraged.” Let’s first decode the communist ethos. The era of communism in China, as in the erstwhile Soviet Union, has been hostile to the environment. This hostility intrinsically stands in the way of long-term economic growth of communist China. As James Kynge writes in his highly perceptive book, China Shakes the World: The Rise of a Hungry Nation, the era of communism characterised “wasteful exploitation and disrespect for the environment”. He quotes Mao exhorting his people in 1940 to “conquer and change nature and thus attain freedom from nature”. Kynge continues, “Those comments had in them the seeds of the disasters and damage that followed; the famine, desertification, pollution, erosion, water shortages and disease.” In this backdrop, are we surprised that China is already waging water wars with its neighbours, including India. And Covid, man-made or natural, found its origins in China! As for governance and economy, China is a victim of its own hype. As James Palmer puts it quite succinctly, “Nobody knows anything about China: Including the Chinese government.” Dikotter explains this in his 2022 book, China after Mao: The Rise of a Superpower: “Every piece of information is unreliable, partial or distorted. We do not know the true size of the economy, since no local government will report accurate numbers, and we do not know the extent of bad loans, since the banks conceal these. Every good researcher has the Socratic paradox in mind: I know what I don’t know. But where China is concerned, we don’t even know what we don’t know.” Dikotter exposes the intrinsic rot in the Chinese economy. “Growth (in China), for decades, had depended on debt, which had risen slowly from a very low level between 1980 and 2010. Between 2010 and 2020, however, growth doubled while debt trebled, standing at 280 percent of output. The country’s dependence on debt should have been reduced by shifting demand from investment in infrastructure projects towards more domestic consumption. Yet household consumption could not be increased much further, for one very simple reason: most of the wealth flowed to the state, not to the people.” Conclusion China is a classic case of a state that is filthy rich, while its people remain poor. Former Chinese premier Li Keqiang opened the lid on the sorry state of affairs when he said in May 2020 that more than 600 million people survived on a mere $140 a month, which, as per Dikotter’s assessment, was “insufficient to rent a room in a city”. Still, China seems to be better placed that it was in the late 1980s and early ’90s. Philip P Pan writes about meeting Chen Guangcheng, a blind legal advocate, just before his arrest, in ‘Epilogue’ of his book, Out of Mao’s Shadow: The Struggle of a New China, written just before the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Chen asked Philip how long he thought the communist party could survive in China. “I told him that when I was studying Chinese in Beijing in the early 1990s, I honestly thought the party’s fall from power might be imminent, perhaps after the death of Deng Xiaoping, who was ageing and in poor health at that time. I didn’t want to leave the country at the end of the semester because I didn’t want to miss it, I recalled. But now I felt foolish for being so naïve.” Chen smiled and pulled Philip’s leg by saying that the latter was “abandoning” the Chinese people; on a serious note, he agreed “it made no sense” for him to wait. Chen however hoped to see a Chinese revolution “in our lifetime”. The ongoing protests may not be that moment of reckoning for the communist party, but it definitely is a warning signal that all’s not well in China. More so for Xi, who must have had a shocking reality check soon after the euphoria of becoming the President of China for the record third term! But then that’s been the template for most autocrats. When they believe they are unchallenged, they fall from grace — and power. After all, those who live by the sword, invariably die by the sword. The author is Opinion Editor, Firstpost and News18. He tweets from @Utpal_Kumar1. Views expressed are personal. Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram .

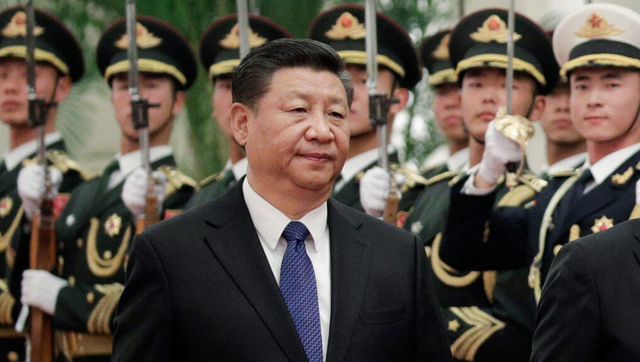

Xi Jinping may scrape through protests with bruises: But, remember, China is not as strong as it appears

Utpal Kumar

• December 1, 2022, 06:59:28 IST

History might suggest most tyrants appeared invincible till they fell at the first collective punch from protesters. This, however, doesn’t mean a regime change is on cards in China; it may be a personal humiliation for Xi Jinping

Advertisement

)