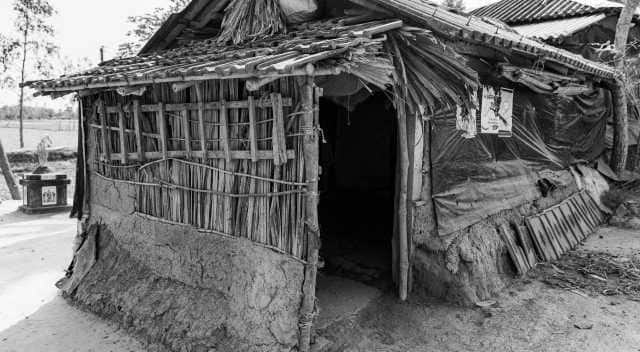

The Indian Sundarbans is truly a place like no other. It is difficult to put into words how different life in this place is. In fact, it is not until you find yourself in this unique watery world of mangled mangrove roots, bordering a seemingly endless expanse of water, twisting and turning in every visible direction, that one can even begin to grasp how incredibly difficult life must be for the people who call this wild environment home. [caption id=“attachment_10863741” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Mangrove roots, a ubiquitous sight in these parts. Image courtesy Polina Schapova[/caption] Part of the largest continuous mangrove forest in the world, this landscape is dotted with islands of different sizes, containing pockets of human habitation, precarious in their very existence, but also inhabited by a whole host of wild creatures. From the elusive tigers, who live primarily on protected reserve forest islands, but think nothing of the occasional meander through neighbouring island villages in search of food, villages inhabited by people; to the heavyweight saltwater crocs who inhabit the murky waters surrounding the islands, in which the villagers regularly fish; to the 56 types of snake found on these islands, not least of which is the reptile King himself, the king cobra. The first permanent inhabitants of this archipelago of islands came here to escape the Bengal famine of the early 1940s, as, despite the dangers of being eaten by a crocodile or a tiger, this land promised them the one thing they prized above anything else at that time — a ready availability of free food (fish and crabs in the surrounding water, honey in the trees, land to grow rice, etc) — with more people streaming in over the next few decades, following the difficult formation of Bangladesh. They came because they had nowhere else to run to, they adapted to this most unusual of living environments, and, in spite of all the hardships thrown at them by mother nature, they found their own balance, and they stayed. At the last count (2011 Census) there were 4.4 million people living there, almost half of whom live below the poverty line. [caption id=“attachment_10863681” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  There are no cars on the island, since there are not really roads, as such, so carts of various types are primarily used for the movement of people and things, some are attached to bicycles, others to motorbikes. Image courtesy Polina Schapova[/caption] Communities here exist in a largely informal subsistence economy structure, growing much of what they consume and sell, as well as relying heavily on the natural resources, which can be freely collected in the waters and forests that surround them; nothing is wasted here. International and local tourism provides much-needed job opportunities, as well as serves as the main external injection of cash for these islands. [caption id=“attachment_10863751” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  A tourist boat awaits the return of customers, following the collapse of the tourism industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Image courtesy Polina Schapova[/caption] The daily rhythm of life here is dictated by the tides, as the waters surrounding the islands rise and fall twice a day according to nature’s predictable timetable. Predictable that is, until a cyclone decides to pass by and cause untold damage and destruction to this already vulnerable habitat, upsetting the careful balance with nature that the human residents have developed over the course of many years of living in this beautiful but harsh world, surrounded on all sides by water. Even the occasional cyclone they had learnt to cope with, despite the immense devastation they cause, but now they find themselves at the mercy of increasingly more powerful cyclones, hitting the islands far more frequently than in decades gone by. [caption id=“attachment_10863621” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  There are many destroyed and abandoned buildings scattered all over the village, evidence of the devastation caused by cyclones. Image courtesy Polina Schapova[/caption] Rethinking risks report The earth is changing, climate change is making weather increasingly unpredictable and volatile everywhere, with the frequency and intensity of cyclones on a clear rise, and so it is in vulnerable areas like the Sundarbans that the true impact of these climate changes is felt hardest. And when more than one major disaster strikes a place like this at once, such as the concurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic and tropical cyclone Amphan, and later cyclone Yash — the result is a plethora of cascading knock-on effects right across communities, sectors and systems, negatively impacting and exacerbating any preexisting vulnerabilities in these communities. Significant distress and hardship blows are dealt to the income, education, health, gender bias, safety and the overall lives of these people, lives and systems, which were already precarious at best to begin with. The examination of such cascading systemic risks was the focus of a recent report published by UNU-EHS (United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security) and UNDRR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction) on ‘Rethinking Risks’. The report titled Understanding and managing cascading and systemic risks: Lessons from Covid-19 used in depth case studies of five vulnerable areas around the world to examine the impact of COVID-19 and the consequent systemic risks across different countries, demographics and communities, to show the complex nature of our interconnected world, and to present lessons learnt for future risk management. [caption id=“attachment_10863601” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Fresh water is distributed throughout the village through a network of community tubewells such as this one. Image courtesy Polina Schapova[/caption] The five case studies were conducted in Guayaquil Ecuador, Maritime Region Togo, Indonesia, Cox’s Bazaar Bangladesh, and Sundarbans India. Teams of videographers were sent out to some of these areas to film their stories first hand and I was fortunate enough to be the person tasked with interviewing and filming the stories of the Sundarbans people for this project. Pandemic + Cyclone = Double Trouble It was not sickness from the COVID-19 virus itself that caused hardship for communities living in this area. Instead it was the implementation of nationwide lockdowns, put in place in order to protect the overstretched healthcare system in India from being overloaded to the point of collapse, that wreaked havoc on the lives of the people of the Sundarbans. Due to the very nature of the subsistence economy that their lives depend on, stay at home orders and a complete ban on movement of people and goods between states and countries spelt disaster for the income and nutritional needs of the people living here. The situation was compounded when cyclone Amphan hit the islands during the first Covid wave, with cyclone Yash hitting it during the second wave, and the intense devastation they brought in their wake. The lives of the people inhabiting these islands went from difficult to nigh impossible. It would not be an exaggeration to say that their mere existence became a matter of survival. Ratan Jana is a tour guide, who lives in the Dulki village. He says, “Compared to the previous cyclones, the latest ones are more severe. As a result, the consequences were more severe than what we could have prepared for. After the cyclone hit, a major crisis we faced was a shortage of drinking water, as all the freshwater in the area turned into saltwater, we had no water to drink. Our priority was to survive without water for at least 3-4 days and to save the animals. After that, if we got any aid, we would survive, or else, we were ready to accept our fate.” [caption id=“attachment_10863581” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Ratan Jana, 33 years old, tourist guide, Dulki village is on a local fishing boat. Image courtesy Polina Schapova[/caption] Lockdowns meant that the villagers lost access to almost all their sources of food supply, both locally grown and externally acquired. Stay at home orders meant that they could not tend to rice fields to grow their own rice in their villages, nor could they go out to fish in the open water, or to catch crabs. They also lost access to the protected forest reserves (which require official passes in order to be able to enter them), so they could not collect calorie rich honey either. Disruption to major national supply chains throughout the country meant that the supply of food coming in from the mainland was also disrupted, though few could afford to buy anything from outside by that point anyhow, since most people’s incomes were severely damaged. The tourism industry had collapsed completely, affecting a huge proportion of the inhabitants of these islands, who relied on jobs in this sector. Earning money from doing agricultural jobs was also not possible under lockdown rules, selling produce grown on your land/in your ponds was no longer viable either, since there was no way to move around to reach a market where goods could be sold. All this meant an almost total collapse of income for the majority of the local population. [caption id=“attachment_10863781” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Every house in the village has its own pond, which acts as a larder and is used for farming fresh water fish, which form an essential part of the islanders’ daily diet. Image courtesy Polina Schapova[/caption] “In a word, lockdown, Covid and the cyclones have left us destitute. My house has been completely damaged. We are still yet to recover from that loss. My family members who previously helped us financially by farming cannot do so now. Everyone, having lost their job, is solely dependent on me right now. My profession of working as a tourist guide was also affected in the past two years due to lockdown. We are still trying to get along, dealing with the suffering, but if this situation continues for long, it will be impossible for us to even survive.” says Ratan. When cyclones pound the islands of the Sundarbans, the villagers’ only protection from the huge waves and rising waters is a small man-made mud bank of a dam, which surrounds the island. But when that dam is damaged and breached, the entire island floods with salt water, which causes immense damage to the islanders’ ability to grow their own food, and this is exactly what happened with both cyclones Amphan and Yash. Salt water flooding causes long term devastation to the land, because the salt poisons the soil, taking upwards of 10 years to recover and return to being farmed again. The lack of crops then directly affects both the nutrition and income needs of the villagers, since they cannot grow food for themselves to eat, or to sell it to supplement their income. [caption id=“attachment_10863811” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Dried up rice fields, following their destruction by salt water flooding during the recent cyclones. Image courtesy Polina Schapova[/caption] Added to this is the damage caused to the ponds on which they rely, where they farm fresh water fish, both for consumption and sale. Freshwater fish die when the ponds are flooded with salt water. Each house has its own pond, which is used as a place to wash both bodies and clothing, but, more importantly, it serves as a larder to farm the fish, which form a large part of the villagers’ diet, as well as being sold at the market for supplementary income. All this became impossible once the ponds were flooded by the rising waters brought about by the cyclones. As Ratan explains: “Our lives are mostly dependent on three things: Our farmlands; the pond where we store water and fish, as a source of food for the entire year; and thirdly, our mud-built houses for shelter. But owing to the cyclone, saltwater invaded our locality and damaged all the three important things on which we depend.” [caption id=“attachment_10863691” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Most village houses are made of locally available materials, namely mud and wood, and as such, they are deeply vulnerable to destruction by rising waters during the times of cyclones. Image courtesy Polina Schapova[/caption] School closures on a national level meant that education was severely disrupted for the children of the Sundarbans, because, unlike elsewhere, online tuition was not a viable possibility out here. Not only do few people own the kind of smart phone required to be able to access online tuition classes, but the internet service itself is not reliable enough to make online tuition a reliable way to study. Moreover, for the youngest and poorest children in rural areas, a system of government schools exists throughout India called Anganwadi. [caption id=“attachment_10863851” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  One of the children who attend the Anganwadi school. Image courtesy Polina Schapova[/caption] These schools act as child care centres of sorts in rural areas for kids under the age of 5, and one of the vital roles they play is the provision of a ‘daily meal’ for the children most in need of it. This one hot meal a day, consisting of an egg, dal, rice and some boiled vegetables, plays a vital role in the lives of many of the needy children and is often the main incentive to get these children to attend school in the first place. School closures for two years meant that even this daily source of nutrition was lost. [caption id=“attachment_10863871” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  The daily meal being given to the children at the Anganwadi school. Image courtesy Polina Schapova[/caption] Minakshi Chakraborty is the headmistress of the Anganwadi centre in the Paschim Para village. She says, “During the lockdown, the school remained completely closed. The food given to the children from our school is to combat nutrition deficiency. As the school closed and the food supply stopped during the lockdown, every child suffered from weight-loss. Here they eat an egg every day, which is impossible for their parents to afford at home. Since the schools were closed, they did not get any of these foods. Now that the schools have reopened, we have noticed that many of them have lost significant weight.” [caption id=“attachment_10863181” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Minakshi Chakraborty, 30 years old, headmistress of the Anganwadi school no 236, Paschim Para village. Image courtesy Polina Schapova[/caption] Minakshi speaks in the video below, which was shot by United Nations University - EHS about living through this incredibly difficult time.

Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)