S Murlidharan Sexual harassment has been given a large berth in the newly minted law called Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, but the punishment that could be meted out is not deterrent enough unless the offence is made out to be culminating in rape. Section 509 of the Indian Penal Code visits such misdemeanors or sexual harassments with a fine or imprisonment for one year or both—a light slap on the wrist which Lotharios would happily take in their swaggering strides. Indeed, it is a tad curious that a special law leans on an antique provision in the IPC when the avowed intention of any special law at least in terms of the expectations it engenders in people is a stiffer than normal punishment being meted out. In other words, one would have expected incarceration in the prison for a year for sexual harassment in a park but a more rigorous one for the same offence in a workplace. The special law comes as a damp squib not only on punishment but on other issues as well. [caption id=“attachment_124503” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

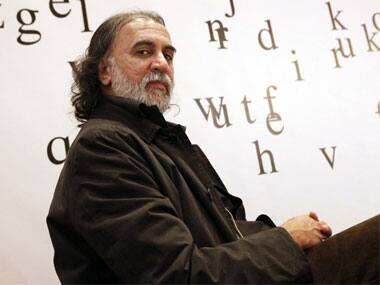

Tarun Tejpal. AFP[/caption] The lynchpin contemplated by the sexual harassment law is the internal complaint committee, to be sure, dominated by females. The aggrieved female employee is supposed to make a complaint to such a committee or to a local committee where for some reason there is no internal committee within the organisation. Both the committees are empowered to arrive at a settlement. One wonders what the terms of the settlement with its implications of compromise could be. To be sure, the sexual harassment law explicitly rules out financial compensation as the basis for settlement but still the term ‘settlement’ bristles with doubts. Income tax settlements always come with images of some wink-wink nudge-nudge. One also wonders whether Tehelka management is keen on settlement that would minimize the damage to the organization and the harasser. The committees can even while arriving at settlement recommend monetary penalties by way of deductions from employee’s salary besides besmirching his record with a mention of misconduct. But this by itself is no big deal. The harassed woman of course can file a complaint to the magistrate directly without recourse to the internal committee mechanism but being a non-cognizable offence as made clear by the sexual harassment law one wonders whether the police can initiate a suo motu action in such matters. The Goa government in L’Affaire Tarun Tejpal is waxing eloquence that it can but certainly it cannot, not under the sexual harassment law unless the offence is serious enough, amounting to rape as per the extended meaning attributed to the term by the recently rejuvenated Indian Penal Code. The point is if the harassed woman is not going to complain to the magistrate, the matter would largely be an in-house affair culminating in a meek settlement. In-house justice is invariably a farce. The Medical Council of India till date has not volunteered to tick off one its members for medical negligence by cancelling his membership. The Advertising Standards Council of India too takes a lenient view of offensive advertisements. The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India does not act unless there is a strong public opinion against erring auditors as happened in Satyam. Ditto for the Bar Council of India. All these are close-knit clubs of the concerned fraternity which impelled the redoubtable Justice Krishna Iyer to remark who would audit the auditors, who would judge the judges and who would police the police. To be sure the internal committee on sexual harassment also has outside members but while outsiders can be counted upon to be impartial, an expectation belied by the so-called independent directors of companies, they are also notoriously apathetic with couldn’t-care-less attitude marking their presence. The truth is the medical community is shaking in its boots ever since the consumer courts started asserting themselves overcoming the protest by doctors that judges constituting such courts are always out of their depths because the knowledge called for is esoteric. Indeed the consumer court dispensation has proved that while the judges themselves might be lacking in esoteric knowledge that need not be a serious handicap in giving an even-handed justice—esoteric knowledge can be sought from experts in the field with second and third opinions eliminating the danger of bias. In the event, despite the howl of protest, Tarun Tejpal might after all get away with the self-awarded punishment of six months’ exile. For all one knows the BJP might not get to fish in the troubled waters, taking sadistic delight in the discomfiture of Tehelka and its promoter who have often been a thorn in its flesh.

Tarun Tejpal. AFP[/caption] The lynchpin contemplated by the sexual harassment law is the internal complaint committee, to be sure, dominated by females. The aggrieved female employee is supposed to make a complaint to such a committee or to a local committee where for some reason there is no internal committee within the organisation. Both the committees are empowered to arrive at a settlement. One wonders what the terms of the settlement with its implications of compromise could be. To be sure, the sexual harassment law explicitly rules out financial compensation as the basis for settlement but still the term ‘settlement’ bristles with doubts. Income tax settlements always come with images of some wink-wink nudge-nudge. One also wonders whether Tehelka management is keen on settlement that would minimize the damage to the organization and the harasser. The committees can even while arriving at settlement recommend monetary penalties by way of deductions from employee’s salary besides besmirching his record with a mention of misconduct. But this by itself is no big deal. The harassed woman of course can file a complaint to the magistrate directly without recourse to the internal committee mechanism but being a non-cognizable offence as made clear by the sexual harassment law one wonders whether the police can initiate a suo motu action in such matters. The Goa government in L’Affaire Tarun Tejpal is waxing eloquence that it can but certainly it cannot, not under the sexual harassment law unless the offence is serious enough, amounting to rape as per the extended meaning attributed to the term by the recently rejuvenated Indian Penal Code. The point is if the harassed woman is not going to complain to the magistrate, the matter would largely be an in-house affair culminating in a meek settlement. In-house justice is invariably a farce. The Medical Council of India till date has not volunteered to tick off one its members for medical negligence by cancelling his membership. The Advertising Standards Council of India too takes a lenient view of offensive advertisements. The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India does not act unless there is a strong public opinion against erring auditors as happened in Satyam. Ditto for the Bar Council of India. All these are close-knit clubs of the concerned fraternity which impelled the redoubtable Justice Krishna Iyer to remark who would audit the auditors, who would judge the judges and who would police the police. To be sure the internal committee on sexual harassment also has outside members but while outsiders can be counted upon to be impartial, an expectation belied by the so-called independent directors of companies, they are also notoriously apathetic with couldn’t-care-less attitude marking their presence. The truth is the medical community is shaking in its boots ever since the consumer courts started asserting themselves overcoming the protest by doctors that judges constituting such courts are always out of their depths because the knowledge called for is esoteric. Indeed the consumer court dispensation has proved that while the judges themselves might be lacking in esoteric knowledge that need not be a serious handicap in giving an even-handed justice—esoteric knowledge can be sought from experts in the field with second and third opinions eliminating the danger of bias. In the event, despite the howl of protest, Tarun Tejpal might after all get away with the self-awarded punishment of six months’ exile. For all one knows the BJP might not get to fish in the troubled waters, taking sadistic delight in the discomfiture of Tehelka and its promoter who have often been a thorn in its flesh.

Why Tejpal may get away with his self-imposed six-month exile

FP Archives

• November 23, 2013, 11:03:53 IST

Under the new law, the punishment that can be meted out is not deterrent enough unless the offence is made out to be culminating in rape.

Advertisement

)