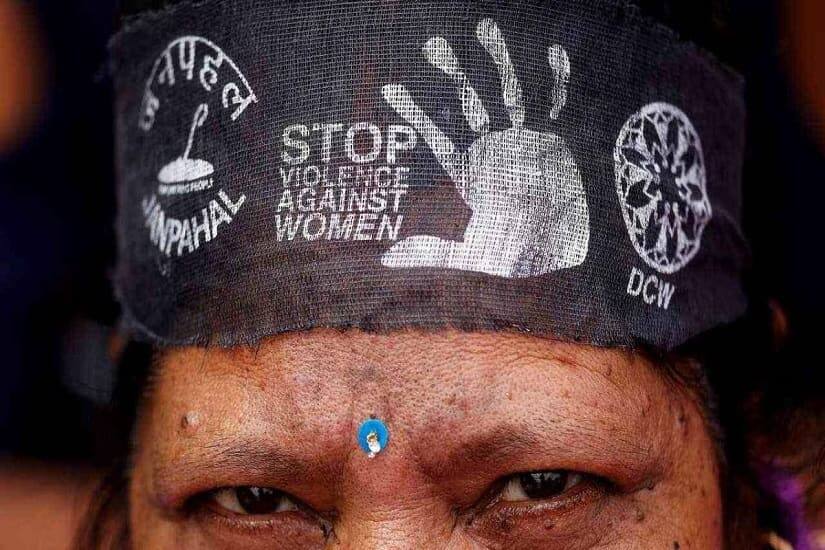

In the mirror Kirsty was made to hold up to her face as they gang-raped her, he looked into her eyes, and remembered “seeing a documentary about some animal being eaten from behind while its face seemed to register disbelief, fear, and self-hate at its own impotence”. Fear, recalled Roy Strang, the character at the centre of Irvine Welsh’s disturbing masterpiece Marabou Stork Nightmares, had contorted her face into something resembling “one of the female prisoners in concentration camp films”. Even the national lockdown has done nothing to slow India’s epidemic of savage violence against women: In recent weeks, a 10-year-old was gang-raped and left for dead in a field in Bihar’s Vaishali; a seven-year-old was raped and blinded in Damoh; a young woman was raped and beaten by seven men in Betul. Now, there’s the grim story of the Instagram group BoisLockerRoom, where students from some of the National Capital Region’s top schools posted photographs of fellow-students with offensive sexual comments, discussed plans to gang-rape them, and made threats to murder women who challenged their operation. The execution of the men responsible for torturing and raping Jyoti Singh on a Delhi bus in 2012 has deterred nothing. That’s because the problem isn’t on Instagram or some ill-lit street. It is in our homes, where we’re rearing our sons, the rapists. *** For many young men in India’s cities and towns, the waste-land inhabited by Welsh’s Strang will be intimately familiar. Together with sport, drinking and brawling, violent misogynistic behaviour is part of the series of rituals through which teenagers pass into the world of men. Innuendo and sniggering about the bodies of school and college friends is the starting-point of a spectrum of behaviours that runs through misogynist social media commentary, street sexual harassment and on to rape. [caption id=“attachment_8339531” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Even the national lockdown has done nothing to slow India’s epidemic of savage violence against women. Representational image. File Photo/Reuters[/caption] Less than six months ago, students at an elite Mumbai school — among them the son of a prominent woman politician, were caught running a group similar to BoisLockerRoom. Even a casual search will show that there are dozens of similar circles still online, among them a Reddit group at a well-known university in Chennai targeting women studying at the institution. For the most part, these groups — and the behaviours of the young men who join them—mimic a great wash of similar platforms catering to male undergraduates in the United States. Total Frat Move, for example, invites members to discuss the bodies of women students, and rate them on a 1-5 scale. There are similar groups catering to more violent fantasies, directed not only at students but also women teachers. “The men own and the women are owned,” scholars Nathian Rodriguez and Terri Hernandez have noted of these groups. “Kill left, fuck middle, marry right,” they record one Instagram user as saying. In 2012, the role of social media as a stage for the performance of sexual violence exploded into full public view, after star high-school students in Steubenville raped a girl incapacitated by alcohol — and then shared what had happened using Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram. Nancy Schwartzman’s powerful documentary Red, Roll, Red shows the community rallied around the perpetrators, and revelled in shaming the victim. President Donald Trump’s infamous 2016 remarks — “Grab them by the pussy,” he advocated, “when you’re a star, they let you do it” — illustrated how central sexual violence was in American mass culture. There is disturbing evidence that hard-won gains in the war against sexual violence are being rolled back by this misogynistic tide. From 1993 on, United States Bureau of Justice statistics show, levels of sexual assault and rape declined steadily, the consequence of sustained public campaigns around gender. For the last decade, though, sexual assault and rape plateaued, and have shown signs of rising again. Though causality is hard to prove, it’s likely that social-media fuelled misogyny has at least something to do with this phenomenon. For millions of young people, the entitled, sexually aggressive world of American fraternity boys is an aspirational ideal: the songs of Badshah or Yo-Yo Honey Singh speak to precisely this zeitgeist. Put another way, violent fantasies involving the sexual subjugation of women are too ordinary to be considered a deviance: They are, instead, the norm. To see this culture as a western import, though, is too easy: the young white college-boy might be a secret god for millions of young men in India, but the problem runs far, far deeper. *** India’s transforming economy and urban landscape has produced a mass of young men with few prospects and even less agency. This disempowerment takes various forms. Even as working class families invest ever-more in their children’s education, employment has become increasingly casualised. Few can have any prospect of realising their families’ expectations. Elite families are able to purchase their children greater opportunities — but this opens the door to lives built on cash, not the self-respect that comes from work. Coddled by son-worshipping parents, young men of all social classes are only rarely able to realise the investment and hopes vested in them: they are fated to be lesser men than culture calls on them to be. To some, violence against women offers at least the simulacrum of real agency and power. [caption id=“attachment_5817471” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Hard-won gains in the war against sexual violence are being rolled back by the current misogynistic tide. Illustration courtesy Namaah K for Firstpost[/caption] Few cities, moreover, have sites where masculinity might come to terms with the increasing presence of women in the workplace and public spaces. Both public and private schools, for example, rarely devote the same resources to sports for girls that they do for boys; there are, particularly in working class milieus, almost no opportunities for collaborations across gender in the arts and culture. Law-enforcement efforts to make public space safe for women remain grossly underfunded. For all practical purposes, the world young Indian men inhabit is segregated by gender. In its place, the digital world and the street becomes the stage for acting out adulthood, through substance abuse and sexual violence. Young men of all classes see women as status-enhancing commodities — to be had by force, if they cannot be purchased through wealth or status. To this, we must add the fact that violence is the shared language of the Indian family. In 2007, the Ministry of Women and Child Development surveyed 12,477 children to learn of their experience of abuse. About 68.99 percent of children, over half of them boys, reported suffering physical violence. Maulana Azad Medical College researcher Deepti Pagare discovered, during a survey of boys at New Delhi’s Child Observation Home, that 76.7 percent reported physical abuse. Half of them actually bore clinical evidence of violence — the perpetrators, in more than half of all cases, their own fathers. In 2013, the National Family Health Survey reported every third Indian woman aged 15-49 had experienced domestic violence; one recent survey placed the figure even higher, at around 40 percent. In many cases, the data suggests, young men have simply learned their behaviours from their fathers. Then, numbers of young people are being brought up by no-parent families — families that fathers have abandoned or are largely absent from, and where mothers work long hours. Elsewhere in the world, too, this social crisis has been linked to sexual violence. South African researcher Amelia Kleijn, in a 2010 study of child rapists, found most had deprived childhoods marked by “physical and emotional abuse, as well as neglect. Last, there is a crisis of sexuality. Few men, working class or rich, have access to a sexual culture which allows them sexual freedoms or choices. The crisis is exacerbated by the fact that sections of urban elites participate in a sexual culture which is relatively liberal — a culture that young men can watch on television and in public spaces, but never hope to participate in. For some, the sexually independent woman is thus enemy to be annihilated. For many men, then, violence against women works much as drugs do for addicts: it offers at least the illusion of empowerment where none exists, fixing feelings of rage and impotence. This, in turn, points to a wider malaise. Marxist scholar Antonio Gramsci noted that Fascism arose in a society “where mothers educate their infant children by hitting them on the head with clogs”. How men behave — on the streets with women, with other men, with animals — is taught. In our society, violence is not an aberration; it is the tie that binds us. India needs a masculinity that does not involve violence. Moral sermons, though, won’t cut it: equality for women can emerge only from a culture that genuinely values rights for all. And the conversations on which it will be built have to begin in our living rooms, with our sons.

The execution of the men responsible for torturing and raping Jyoti Singh on a Delhi bus in 2012 has deterred nothing. That’s because the problem isn’t on Instagram or some ill-lit street. It is in our homes, where we’re rearing our sons, the rapists.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)