Editor’s note: Kolkata and the Sundarbans face a deadly melange of climate change impacts: intensifying heat waves and rainfall extremes, an exceptionally rapid rise in sea levels and intensifying cyclones. Chirag Dhara, a climate physicist, visited Kolkata and the Sundarbans in November 2018. He interviewed a wide cross-section of people – college students and professionals, taxi drivers and street dwellers – on their experience of changes in their city’s climate. He also spoke to experts and activists working in health, science and environment. This five-part series integrates public perception with expert opinion. It contextualizes local climate trends within country-wide and global trends, using photographs, videos, satellite imagery, infographics, concept schematics and the latest developments in climate research. Important scientific concepts have been simplified to better explain the causes and consequences of these changes. This is the third part of the series. Read all the stories in the series here

Primary School on Sagar Island in the Sundarbans in January 2014. Image courtesy: Nagraj Adve[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_6124211” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Primary School on Sagar Island in the Sundarbans in January 2014. Image courtesy: Nagraj Adve[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_6124211” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

The same school four years later in November 2017, consumed by the rising waters of the Bay of Bengal. Image courtesy: Utpal Giri[/caption] The corroding Sundarbans The photographs above of a school on the edge of Sagar Island, in the Indian Sundarbans, were taken less than four years apart. Classes were in full swing when Nagraj Adve, a climate change activist and writer,

visited in early 2014

. At the time, the school was a few hundred metres from the water line. While it was not uncommon even then for high tide waters in the monsoon to reach the school, waters in the Bay of Bengal have swelled so rapidly that the sea has now completely swallowed the school and intrudes a hundred metres beyond it. The school has moved half a kilometre further inland as have families that chose to continue living on the island. Others have left, now effectively climate refugees. Sadly, the plight of the school is the rule, not the exception, in many parts of the Sundarbans. The two overlaid images of the Sundarbans below were acquired by NASA satellites 19 years apart. A cursory visual inspection is all it takes to see how the coastline has eroded almost everywhere along the Bay-facing coastline. Some small islands have gone completely under. The Indian Sundarbans images by NASA’s Landsat satellites 19 years apart. Left: November 2018. Right: November 1999. Note the erosion of the bay facing the coastline. Data access:

https://landlook.usgs.gov/viewer.html

Why is the Sundarbans eroding away? What does its future hold? To what extent are we — humans — responsible for these children having lost their school? Global sea levels are rising [caption id=“attachment_6121191” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

The same school four years later in November 2017, consumed by the rising waters of the Bay of Bengal. Image courtesy: Utpal Giri[/caption] The corroding Sundarbans The photographs above of a school on the edge of Sagar Island, in the Indian Sundarbans, were taken less than four years apart. Classes were in full swing when Nagraj Adve, a climate change activist and writer,

visited in early 2014

. At the time, the school was a few hundred metres from the water line. While it was not uncommon even then for high tide waters in the monsoon to reach the school, waters in the Bay of Bengal have swelled so rapidly that the sea has now completely swallowed the school and intrudes a hundred metres beyond it. The school has moved half a kilometre further inland as have families that chose to continue living on the island. Others have left, now effectively climate refugees. Sadly, the plight of the school is the rule, not the exception, in many parts of the Sundarbans. The two overlaid images of the Sundarbans below were acquired by NASA satellites 19 years apart. A cursory visual inspection is all it takes to see how the coastline has eroded almost everywhere along the Bay-facing coastline. Some small islands have gone completely under. The Indian Sundarbans images by NASA’s Landsat satellites 19 years apart. Left: November 2018. Right: November 1999. Note the erosion of the bay facing the coastline. Data access:

https://landlook.usgs.gov/viewer.html

Why is the Sundarbans eroding away? What does its future hold? To what extent are we — humans — responsible for these children having lost their school? Global sea levels are rising [caption id=“attachment_6121191” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

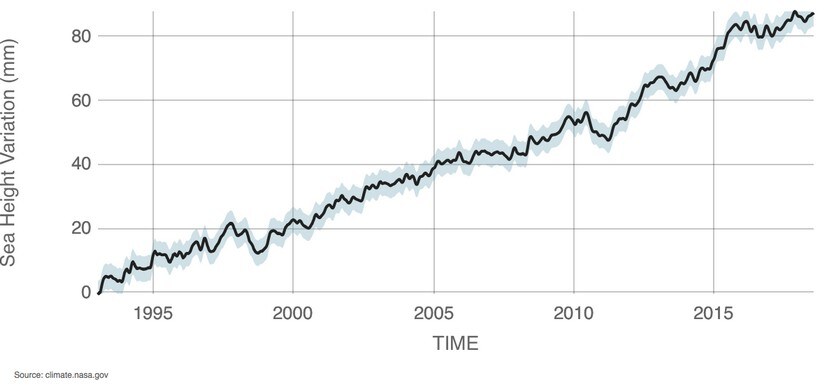

The rise in global sea level on average from 1993 - present. Data source: Satellite sea level observations. Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.[/caption] Sea levels have been rising in all the world’s oceans for the past century. There are many natural reasons why sea levels change, but also two major ways in which human-induced global warming is impacting sea levels today. For one, with rising temperatures, trillions of tonnes of ice have melted in the past century from glaciers and ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica because of global warming, adding vast quantities of water to the oceans. A time lapse of Earth for the past 32 years showing how glaciers are declining. Ice loss from Greenland and Antarctica are not evident in these images because these ice sheets are kilometres thick. Please see the Q&A section below for details. Data:

NASA’s Landsat, ESA’s Sentinel 2A satellite imagery among others.

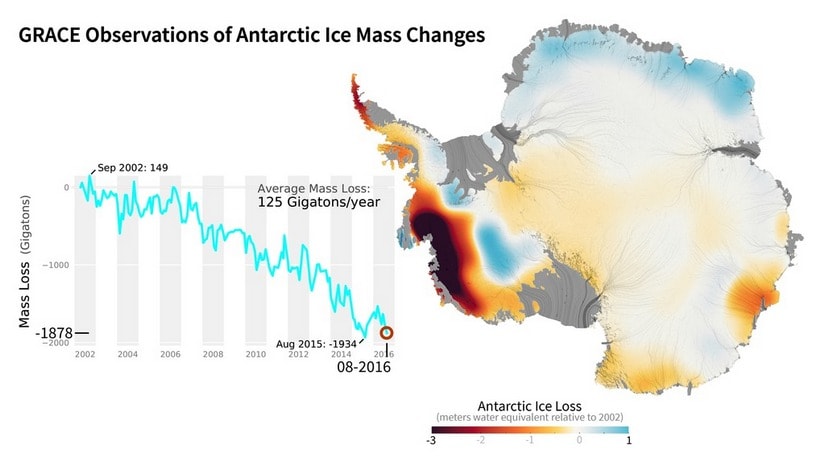

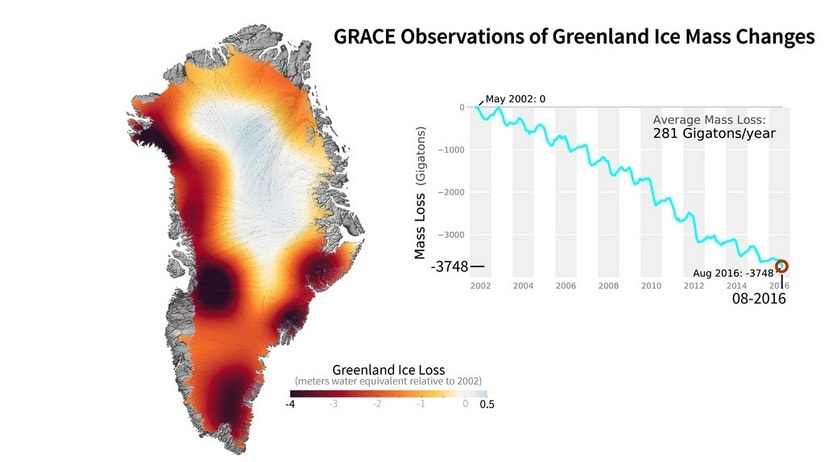

Visualization: Google Earth Engine. For another, water expands as it warms causing the same quantity of water to occupy more space. The combined effect of these two processes is a rise in global sea levels of about 3 mm/year on average. Q&A: How are Greenland and Antarctica contributing to sea-level rise? Greenland in the northern hemisphere and Antarctica at the south pole each hold enormous quantities of frozen fresh water in their kilometre(s)-thick ice sheets. As global temperatures rise, these ice sheets are rapidly melting, adding water to the world’s oceans. Satellites monitoring ice thickness found that nearly 2 trillion tonnes of ice has melted from Antarctica while Greenland has shed nearly 4 trillion tonnes in 14 years of observation alone (2002 – 2016). [caption id=“attachment_6121261” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

The rise in global sea level on average from 1993 - present. Data source: Satellite sea level observations. Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.[/caption] Sea levels have been rising in all the world’s oceans for the past century. There are many natural reasons why sea levels change, but also two major ways in which human-induced global warming is impacting sea levels today. For one, with rising temperatures, trillions of tonnes of ice have melted in the past century from glaciers and ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica because of global warming, adding vast quantities of water to the oceans. A time lapse of Earth for the past 32 years showing how glaciers are declining. Ice loss from Greenland and Antarctica are not evident in these images because these ice sheets are kilometres thick. Please see the Q&A section below for details. Data:

NASA’s Landsat, ESA’s Sentinel 2A satellite imagery among others.

Visualization: Google Earth Engine. For another, water expands as it warms causing the same quantity of water to occupy more space. The combined effect of these two processes is a rise in global sea levels of about 3 mm/year on average. Q&A: How are Greenland and Antarctica contributing to sea-level rise? Greenland in the northern hemisphere and Antarctica at the south pole each hold enormous quantities of frozen fresh water in their kilometre(s)-thick ice sheets. As global temperatures rise, these ice sheets are rapidly melting, adding water to the world’s oceans. Satellites monitoring ice thickness found that nearly 2 trillion tonnes of ice has melted from Antarctica while Greenland has shed nearly 4 trillion tonnes in 14 years of observation alone (2002 – 2016). [caption id=“attachment_6121261” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

There has been moderate ice accretion is some parts of Antarctica driven by ocean circulation patterns. Yet, on the whole, the continent has been losing ice rapidly because of ice-melt. Source:

NASA satellite observations (GRACE)

[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_6124241” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

There has been moderate ice accretion is some parts of Antarctica driven by ocean circulation patterns. Yet, on the whole, the continent has been losing ice rapidly because of ice-melt. Source:

NASA satellite observations (GRACE)

[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_6124241” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Greenland ice is melting twice as fast as on Antarctica. Source:

NASA satellite observation (GRACE)

[/caption] In addition, water expands as its temperature rises, as do most substances, in a process called thermal expansion. This causes the same mass of ocean water to occupy more space at a higher temperature contributing yet more to sea-level rise. Thermal expansion of water for even a small temperature rise so important that it is

considered the single biggest cause of anthropogenic sea-level rise in the long run

, even more important than ice-melt. The combined effect of these phenomena has been to raise global sea-levels by about 3 mm/year on average in recent decades. However, the seas are rising considerably faster in some of the world’s oceans than in others. [caption id=“attachment_6121281” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Greenland ice is melting twice as fast as on Antarctica. Source:

NASA satellite observation (GRACE)

[/caption] In addition, water expands as its temperature rises, as do most substances, in a process called thermal expansion. This causes the same mass of ocean water to occupy more space at a higher temperature contributing yet more to sea-level rise. Thermal expansion of water for even a small temperature rise so important that it is

considered the single biggest cause of anthropogenic sea-level rise in the long run

, even more important than ice-melt. The combined effect of these phenomena has been to raise global sea-levels by about 3 mm/year on average in recent decades. However, the seas are rising considerably faster in some of the world’s oceans than in others. [caption id=“attachment_6121281” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

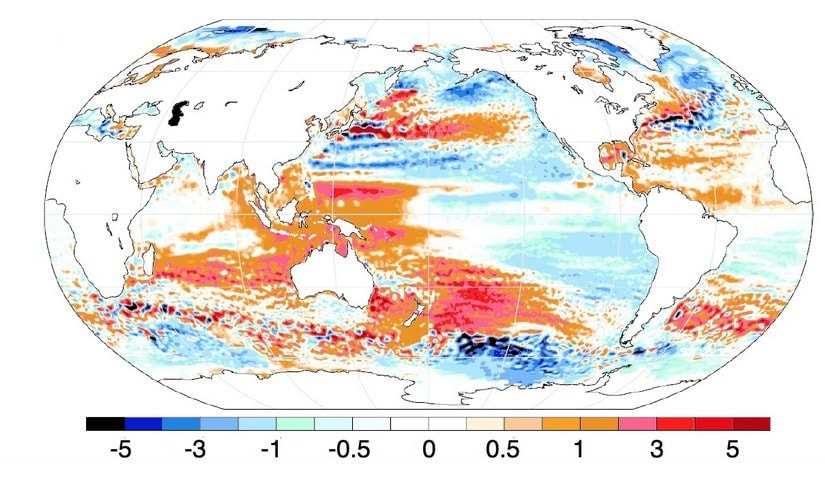

Uneven sea-level rise around the world. The rate at which sea-levels are rising (mm/year) relative to the global average during the satellite era 1993 – 2018. Reds denotes a rate of rise above the global average and opposite for the blues. Of particular interest here is that sea levels are rising faster than the global average in the Bay of Bengal. Source: PNAS[/caption] Sea levels are rising much faster along the Sundarbans’ coastline Natural factors such as how heat is transported by ocean currents and periodic climatic phenomena such as El Niño are some major reasons for why regional differences in sea-level rise come about. Yet, global warming plays into this as well.

Temperatures are rising faster in some parts of the world’s oceans than others

. Consequently, water expands faster swelling the seas more rapidly in those regions. Primarily for this reason, waters of the Bay of Bengal have been rising

up to twice as fast as the global average

at about 4.4 – 6.3mm/year. Unhappily, physical features specific to the Sundarbans and extensive upstream damming of the rivers flowing into it has combined to make the situation even graver. Q&A: Why should a few mm/year rise in sea level be of concern? A sea-level rise of 3 mm per year may not seem like much. Yet, it can produce significantly greater inland sea water intrusion over time especially in low lying coastal areas. The gently sloping area adjoining the coast is called the Continental Shelf, where the average downward slope is only about 0.1o. The 3 cm rise that would occurs in a decade, at current rates of sea-level rise, would cause sea levels to intrude further inland by a disproportionately larger 17 meters (65 feet).

Uneven sea-level rise around the world. The rate at which sea-levels are rising (mm/year) relative to the global average during the satellite era 1993 – 2018. Reds denotes a rate of rise above the global average and opposite for the blues. Of particular interest here is that sea levels are rising faster than the global average in the Bay of Bengal. Source: PNAS[/caption] Sea levels are rising much faster along the Sundarbans’ coastline Natural factors such as how heat is transported by ocean currents and periodic climatic phenomena such as El Niño are some major reasons for why regional differences in sea-level rise come about. Yet, global warming plays into this as well.

Temperatures are rising faster in some parts of the world’s oceans than others

. Consequently, water expands faster swelling the seas more rapidly in those regions. Primarily for this reason, waters of the Bay of Bengal have been rising

up to twice as fast as the global average

at about 4.4 – 6.3mm/year. Unhappily, physical features specific to the Sundarbans and extensive upstream damming of the rivers flowing into it has combined to make the situation even graver. Q&A: Why should a few mm/year rise in sea level be of concern? A sea-level rise of 3 mm per year may not seem like much. Yet, it can produce significantly greater inland sea water intrusion over time especially in low lying coastal areas. The gently sloping area adjoining the coast is called the Continental Shelf, where the average downward slope is only about 0.1o. The 3 cm rise that would occurs in a decade, at current rates of sea-level rise, would cause sea levels to intrude further inland by a disproportionately larger 17 meters (65 feet).

West Bengal's climate change conundrum Part III: Extraordinarily rapid sea-level rise in Sundarbans turns families into refugees

Chirag Dhara

• October 10, 2020, 18:03:22 IST

Satellites have found the sea advancing by a staggering 200 metres (650 feet)/year in parts of the Sundarbans, and a total of 170 square kilometres (the size of Kolkata city) has surrendered to the sea in the 37 years between 1973 and 2010 alone.

Advertisement

)

[caption id=“attachment_6121111” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Sea levels today are about 20c m higher than pre-industrial times (1850s) meaning that land has ceded about 115 metres to the sea in coastal areas with gentle elevation. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report released in October 2018 warns that sea levels may rise up to 77 cm by 2100 even if global temperatures rose “only” to 1.5 C in the next 80 years. The reality we are presently facing is far worse. We are currently on track for temperature rise of 3 to 4 C by 2100. The sinking Sundarbans Contours of river deltas are naturally dynamic being shaped by sediment deposition by the vast amounts of soft, fertile silt transported by the rivers constituting them. Land accretes by sedimentation, but is lost by silt compactification and coastal erosion. Sediment transport into the Sundarbans has been severely affected by upstream damming, especially the Farakka dam in West Bengal built on the Ganga in 1975. Dams trap sediment and greatly reduce downstream transport. As a result, subsidence have outpaced accretion on average in the Indian part of the Sundarbans and the Delta is sinking at a rate of about 2 to 4mm/year. The combined effect of already high rate of sea-level rise in the Bay of Bengal and land subsidence has been an effective sea-level rise in the Sundarbans that is

nearly three times as fast as the global average (~ 8mm/year), and as high as 12mm/year

on Sagar Island. The consequences are all too obvious and exactly what has occurred: Satellites have found the sea

advancing by a staggering 200 metres (650 feet)/year

in parts of the Sundarbans, and a total of

170 square kilometres (the size of Kolkata city) has surrendered to the sea in the 37 years between 1973 and 2010

alone. These are facts that students and teachers of Boatkhali Kadambini School need little convincing about. Impacts of sea-level rise on the Sundarbans Higher sea levels have devastating impacts on low-lying coastal habitats, and the Sundarbans is one of the most densely populated yet biodiverse ones in the world. Aside from the school on Sagar Island becoming permanently inundated in a space of merely four years, the entire stretch where there were

houses and agricultural land has been swallowed by the sea

. The large-scale destruction of Mangroves has exacerbated coastal erosion. The surging seas have turned fertile agricultural lands and groundwater increasingly saline. Families are moving inland or leaving the island entirely, often to big cities like Kolkata, effectively becoming climate change refugees. There is yet another tragedy in store for the Sundarbans. A study focusing on the Bangladeshi Sundarbans (contiguous with the Indian Sundarbans) found that the remaining Tiger habitat and population

would be almost entirely wiped out

for a 28 cm rise in sea levels above the 2000 levels, which is likely to happen in the next 50 to 90 years. Sea levels

are expected to continue rising with increasing intensity in the Sundarbans

. The fate of the Boatkhali Kadambini Primary School is an early warning sign, a precursor, of the devastation the Sundarbans faces. It is the fate that awaits all life in the Sundarbans, humans and animals alike, if we do not heed these signs and act at once to

adapt

if not to mitigate. The author is a climate physicist currently freelancing for Firstpost_. You can get in touch with him on chirag.dhara@protonmail.ch_

End of Article