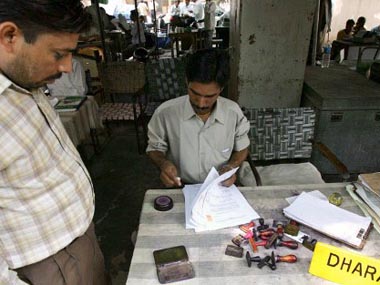

by Abhay Vaidya Corruption in the Indian bureaucracy — be it civil or defence — is once again under sharp focus in the wake of Army chief Gen VK Singh’s extraordinary charge that he was offered a Rs14 crore bribe to approve the purchase of substandard vehicles. Two statements by Gen Singh in his Hindu interview indicate the scale of corruption in the defence establishment: Singh said he was targeted on his date of birth controversy because he had cracked down on corruption. And that the man who offered him the bribe had recently retired from the Army and had told him that “…people had taken money before me and they will take money after me.” What can be more shocking and shameful for a country that even its serving army chief is made to feel helpless by a bribe-giver? Ironically, India has not paid as much attention to the corrupt bureaucrat as much as to politicians even though the corrupt bureaucrat — whether he is from the IAS, IPS or any other service — is far more insidious than the corrupt politician. He is the bigger traitor of the two. The sooner Indians realise this truth, and do something about it, the better it would be for the nation in its battle against corruption. [caption id=“attachment_256253” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“AFP Photo”]

[/caption] Unlike the politician who is always under the public glare and has many enemies and competitors within and outside his party, the corrupt bureaucrat stays hidden from the limelight. He lies embedded in the system, spreading the rot like a cancerous tissue, till some Adarsh housing society scam or a 2G spectrum scam erupts and brings him out in the open. No matter who wins the elections, it’s always win-win for the corrupt bureaucrat because he is sought out by his new political master who knows that he has a limited term to make quick money. At his master’s bidding, such bureaucrats efficiently do the paperwork and move the administrative machinery to favour vested interests. This is the story of big ticket corruption in India, in state after state, driven by the double-faced monster. Look at what is happening in the Adarsh housing society scam in Maharashtra. It was only after the most-recent whiplash from a Bombay High Court bench that the CBI last week arrested IAS officer and state finance secretary Pradeep Vyas, former MLC Kanhaiyalal Gidwani and former deputy secretary in the state urban development department, PV Deshmukh, among others. In fact, it was 14 months ago, in December 2010, that a high court bench had first asked the Maharashtra government why no action had been taken against the bureaucrats in the Adarsh scam who had cleared key files in the revenue and urban development departments, manipulated the system and got flats allotted to ineligible entities, including their relatives. A day after Vyas’s arrest, the Prithviraj Chavan government suspended Vyas and former Mumbai municipal commissioner Jairaj Phathak, also from the elite IAS. Vyas has been accused of accepting false documents as proof of income and granting membership in the society to those who were ineligible. His wife and IAS officer, Seema Vyas, was one of the beneficiaries. Phatak, whose son received a flat in the Adarsh society, is accused of allowing the height of the building to be raised over 100 metres without clearance from the civic body’s High Rise Committee. Last year, former urban development secretary Ramanand Tiwari, who was appointed information commissioner after retirement, was suspended from that post and former principal secretary Subhash Lalla, resigned as member of the state human rights commission. Both are co-accused in the Adarsh scam. Former chief minister Ashok Chavan is among the 14 persons named as accused by the CBI in the Adarsh scam. While all the accused are innocent until proven guilty, what the Adarsh and other scams magnify is the role of top bureaucrats in facilitating corruption. A 2009 Asian survey that ranked Singapore as the country with the best bureaucracy and India with the worst, had provoked a newspaper letter writer to comment eloquently that “Pakistan has been ruined by the army and India by the bureaucracy.” Corruption in the Indian bureaucracy at the top levels has been troubling honest officers too. In December 1996, the Uttar Pradesh IAS Association created a sensation by undertaking a secret ballot to identify the three most corrupt bureaucrats in their midst and hand over the results to the government for necessary action by the investigating agencies. Ten years later, in 2006, a citizens’ group, the India Regeneration Initiative (IRI), headed by a former chief justice of India, decided to enlarge this exercise and identify “20 most corrupt” senior bureaucrats in UP. IRI’s convenor explained that corruption was “eating into the vitals of the system” in UP “and since we know that this malady grows from the top, we need to first do the weeding at the higher echelons of the administration.” Just as corrupt bureaucrats are often favoured and given plum postings, upright ones are hounded and harassed with transfers and cannibalised by their own cadre. A striking example is that of Arun Bhatia who was transferred 26 times in his career of 30 years. Acting on a public interest litigation concerning Bhatia’s transfer, the then chief justice of the Bombay high court termed his transfer as “outrageous” and observed: “We wish to emphasise that during the present days when, unfortunately, corruption and dishonesty are at their peak, honesty and action as per law deserve a pat, rather than punishment. The transfer of Bhatia, in our view, is in the nature of punishment”. Many IAS aspirants admit that although they could have pursued successful and lucrative careers in the corporate world with their top class backgrounds in engineering and management, what draws them to the IAS is the phenomenal power enjoyed by the brahmins of Indian bureaucracy. A white Ambassador with a red, revolving beacon is the first symbol of power for them. As they rise in their careers, their power — and wealth, in the case of corrupt bureaucrats — increases proportionately. This continues- undetected- till one odd scam gets exposed in the media. The corrupt bureaucrat is more insidious than the corrupt politician because he exists in multiples and does far greater damage while remaining largely undetected. The indictment, suspension and arrest of IAS officers and other bureaucrats in corruption-related scams will go a long way in cleaning up the Indian system.

[/caption] Unlike the politician who is always under the public glare and has many enemies and competitors within and outside his party, the corrupt bureaucrat stays hidden from the limelight. He lies embedded in the system, spreading the rot like a cancerous tissue, till some Adarsh housing society scam or a 2G spectrum scam erupts and brings him out in the open. No matter who wins the elections, it’s always win-win for the corrupt bureaucrat because he is sought out by his new political master who knows that he has a limited term to make quick money. At his master’s bidding, such bureaucrats efficiently do the paperwork and move the administrative machinery to favour vested interests. This is the story of big ticket corruption in India, in state after state, driven by the double-faced monster. Look at what is happening in the Adarsh housing society scam in Maharashtra. It was only after the most-recent whiplash from a Bombay High Court bench that the CBI last week arrested IAS officer and state finance secretary Pradeep Vyas, former MLC Kanhaiyalal Gidwani and former deputy secretary in the state urban development department, PV Deshmukh, among others. In fact, it was 14 months ago, in December 2010, that a high court bench had first asked the Maharashtra government why no action had been taken against the bureaucrats in the Adarsh scam who had cleared key files in the revenue and urban development departments, manipulated the system and got flats allotted to ineligible entities, including their relatives. A day after Vyas’s arrest, the Prithviraj Chavan government suspended Vyas and former Mumbai municipal commissioner Jairaj Phathak, also from the elite IAS. Vyas has been accused of accepting false documents as proof of income and granting membership in the society to those who were ineligible. His wife and IAS officer, Seema Vyas, was one of the beneficiaries. Phatak, whose son received a flat in the Adarsh society, is accused of allowing the height of the building to be raised over 100 metres without clearance from the civic body’s High Rise Committee. Last year, former urban development secretary Ramanand Tiwari, who was appointed information commissioner after retirement, was suspended from that post and former principal secretary Subhash Lalla, resigned as member of the state human rights commission. Both are co-accused in the Adarsh scam. Former chief minister Ashok Chavan is among the 14 persons named as accused by the CBI in the Adarsh scam. While all the accused are innocent until proven guilty, what the Adarsh and other scams magnify is the role of top bureaucrats in facilitating corruption. A 2009 Asian survey that ranked Singapore as the country with the best bureaucracy and India with the worst, had provoked a newspaper letter writer to comment eloquently that “Pakistan has been ruined by the army and India by the bureaucracy.” Corruption in the Indian bureaucracy at the top levels has been troubling honest officers too. In December 1996, the Uttar Pradesh IAS Association created a sensation by undertaking a secret ballot to identify the three most corrupt bureaucrats in their midst and hand over the results to the government for necessary action by the investigating agencies. Ten years later, in 2006, a citizens’ group, the India Regeneration Initiative (IRI), headed by a former chief justice of India, decided to enlarge this exercise and identify “20 most corrupt” senior bureaucrats in UP. IRI’s convenor explained that corruption was “eating into the vitals of the system” in UP “and since we know that this malady grows from the top, we need to first do the weeding at the higher echelons of the administration.” Just as corrupt bureaucrats are often favoured and given plum postings, upright ones are hounded and harassed with transfers and cannibalised by their own cadre. A striking example is that of Arun Bhatia who was transferred 26 times in his career of 30 years. Acting on a public interest litigation concerning Bhatia’s transfer, the then chief justice of the Bombay high court termed his transfer as “outrageous” and observed: “We wish to emphasise that during the present days when, unfortunately, corruption and dishonesty are at their peak, honesty and action as per law deserve a pat, rather than punishment. The transfer of Bhatia, in our view, is in the nature of punishment”. Many IAS aspirants admit that although they could have pursued successful and lucrative careers in the corporate world with their top class backgrounds in engineering and management, what draws them to the IAS is the phenomenal power enjoyed by the brahmins of Indian bureaucracy. A white Ambassador with a red, revolving beacon is the first symbol of power for them. As they rise in their careers, their power — and wealth, in the case of corrupt bureaucrats — increases proportionately. This continues- undetected- till one odd scam gets exposed in the media. The corrupt bureaucrat is more insidious than the corrupt politician because he exists in multiples and does far greater damage while remaining largely undetected. The indictment, suspension and arrest of IAS officers and other bureaucrats in corruption-related scams will go a long way in cleaning up the Indian system.

Target bureaucracy, break the backbone of corruption

FP Archives

• March 26, 2012, 19:28:20 IST

Interestingly, the anti-corruption crusaders of all hues are obsessed with political corruption while the real culprit is the babudom.

Advertisement

)