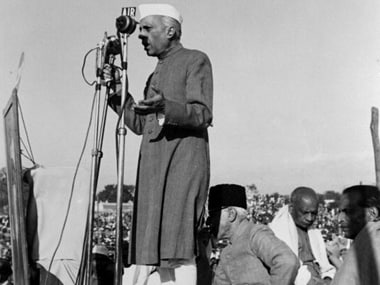

As India struggles over the nature of its identity and as contestations over its nature (or let’s say, soul) grow shriller, a rather curious debate is taking place. This debate pertains to the nature of Jawaharlal Nehru’s ‘legacy’ and its future amid all the fluid and churn that defines India contemporaneity. The debate and its premises are flawed for they assume, a priori, that India owes a debt to Nehru because he was the sole architect of modern India. It was Nehru who, in the world view of these hagiographers, who ‘discovered’ India and bequeathed upon it ideas, institutions and values – pluralism, secularism, tolerance, the modern temper and some may even say democracy – that corresponded to India’s essence. And that, given the nature of India’s contemporary politics - the rise of the far right to political primacy - it is these values and institutions that are in danger and under threat. Or, in other words, the so called ‘Nehruvian legacy’ is under assault and a new idea of India is incubating, one that is diametrically opposed to Nehru’s idea. The former view is akin to the ‘Alice in Wonderland’ fantasy and the latter , if it is conceded there may be some merit to it, is speculative and inferential. To come to pass, it would call for a revolution and would, to quote Naipaul, lead to a ,’Million Mutinies Now’. [caption id=“attachment_1802735” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  February 1948: Pandit Nehru pays tribute to Mahatma Gandhi with Sardar Patel seated in the background. Getty Images[/caption] The Alice in Wonderland view first: While Nehru was indeed an intellectual and even leader of great stature, he merely became an instrument of a larger historical movement and trend, that of, political liberalism. Nehru was hardly original. He was the beneficiary of historical gale of political liberalism (and nationalism) that was sweeping across the then-Imperial metropoles. He appears to have absorbed the basic and fundamental premises of both quite well and then given the mood and temper of the times in colonial India, set to graft these onto India. There then was no special or original insight that Nehru had. This can be validated by his skin deep understanding of economics: his admiration for Fabian Socialism, which he used as a guiding principle for post Independence India’s economic policy is a classic instance. (The redundant Five Year Plans accrued from this and India continues to, in many senses, belabour under these). Nehru was no idealist; he was smitten by a certain ideology and adhered to it. The institutional and ideational rubric that is the hallmark of modern India flowed paradoxically from India’s encounter with colonial modernity. To be fair, while the British rule over India was marked by inequities and iniquities, the British left an institutional and ideational legacy to the country in the form of democracy, the rule of law and Weberian bureaucracy. Nehru appears to have understood this very well but in an attempt to perhaps expunge colonial associations with these ideas, institutions and concepts, set out to ‘discover’ India. This was a vainglorious attempts to draw and tease out some foundational and ‘organic’ idea that could be held to be indigenous. By going, ‘native’, Nehru constructed his, ‘Idea of India’ – an idea which his hagiographers popularized. This Idea of India was and is as mythical as its opposing Idea - the one promulgated by the proponents of Hindutva. Nations, to quote Benedict Andersen, are ‘imagined communities’. To say or assert otherwise is to be guilty of crude and vulgar essentialism. The key, however, is how these imagined communities are willed into being. It is here that Nehru’s role and contribution becomes pertinent. The man extended the residual legacy of colonial modernity onto India and made political liberal the central tenet of his political philosophy and policy. This is, insofar as the ideational and institutional rubric of India that is attributed to Nehru. What about Nehru’s politics? What does the historical record say? Nehru’s egotism, it is held by many, led to the partitioning of the subcontinent. The man could not come to terms with Jinnah. Partition was the inevitable outcome. This pertains to pre-independence India. Post independence India had to deal with the ‘problem’ of Kashmir. Here Nehru practised a smooth and deft realpolitik. He inveigled Sheikh Abdullah and called him a friend and when Sheikh Abdullah questioned the U-turns in policy and politics, Nehru betrayed him. The various opportunities to settle Kashmir for good were squandered by Nehru ‘because of a special attachment to Kashmir’. The question is: how is this for idealism? All this is not to demean the man but to arrive at a sober assessment and perspective. At the time, Nehru was all-in-all, an intellectual par excellence, a great leader but was as human as can be. Attributing super human qualities and originality to him constitutes the fallacy of projection. The institutional and ideational rubric of India predates Nehru. Is this under threat? Maybe. However, to invert India and render it into something grotesque would either call for a bloody revolution or a politics that correspond to inter war European politics. This politics was in the nature of a politics of bitterness, vendetta and revanchism. To transpose this to India successfully would mean that the underlying under currents in India correspond to these themes. Or, in other words, a fundamental discontent must define India for this politics to be successful. This does not appear to be the case. There, however, is some fluid and churn that defines contemporary India. What will this churn lead to? Will the idea of India evolve? Possibly. This change will, however, take place under an institutional and perhaps even ideational firmament that modern India is wedded to. And this will be despite Nehru.

Nehru was all-in-all, an intellectual par excellence, a great leader but was as human as can be. Attributing super human qualities and originality to him constitutes the fallacy of projection.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)