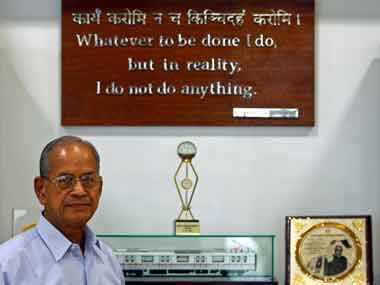

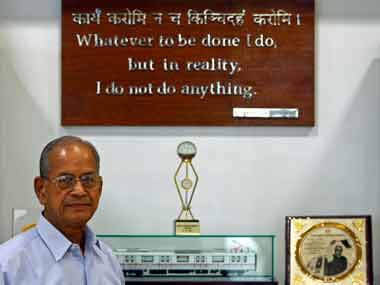

In 2006 something quaint happened: a state funded infrastructure project was completed three years ahead of schedule, sticking to its budget. Many called it a miracle. In a country where infrastructure projects fall behind schedules caught in a web of bureaucracy and political meddling this was a first. The man behind the project, E Sreedharan, became an instant legend and his project, the Delhi metro, became history. He’s fast: On the metro project the average duration of major tenders was 19 days, compared to the three to nine months that is the norm. In 1963, a cyclone washed away parts of Pamban Bridge that connected Rameshwaram to mainland Tamil Nadu. The Railways set a target of three months for the bridge to be repaired. Sreedharan was put in-charge of the execution and he restored the bridge in just 46 days. [caption id=“attachment_170377” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“E Sreedharan in his office. Reuters”]

[/caption] And he likes to do things his way. Unlike most bureaucrats and technocrats working for the government, Shreedharan doesn’t take ’no’ for an answer. When he set out to build an information technology park outside Delhi, the requisite permissions were slow in coming. Sreedharan simply went ahead. Completed in 2005, the IT park now is thriving and houses several high-profile Indian companies, including Genpact, says

Businessweek

. “All the works which the civic authorities are required to do, we did it ourselves without waiting for them,” Sreedharan told

Reuters

. On Saturday, December 31, 2011, Sreedharan called it quits. At 79 he was the oldest technocrat working for the Government of India. Sreedharan officially retired in 1990 but was asked to report back to build the Konkan Railway, before being asked to take over the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation. “For us, time is money. We know that each day is so important and we can’t allow one day to waste,” Shreedharan was quoted by

Reuters

, when asked about Delhi Metro’s success. Perhaps it was this no-nonsense attitude to delivery and sticking to deadlines that led the Delhi government to give him a free hand in to hiring people, deciding on tenders and controlling funds. “The project report of Phase-I envisaged completion in 10 years but one of the first decisions I took was to finish it in seven years. We did it in seven years and three months. There was a query from the government of India, asking why the damn hurry? The money they would have released in 10 years had to be released in seven years. But when they saw the result, they started having confidence and we were able to get what we wanted,” Sreedharan had told

Business Standard

last year. Everyday with the Delhi Metro Sreedharan reminded himself and his employees of his tough deadlines. His desk had a digital clock that counted down the days before the next line must be completed. Similar clocks are found throughout Delhi Metro’s offices and construction sites. His appreciation for punctuality is evident in the way the Delhi Metro functions. Trains run at an interval of 2 minutes 30 seconds between trains at peak frequency at over 90 per cent efficiency when it comes to keeping time. It’s difficult to escape criticism in India, especially if you don’t toe a politician’s line. But even with his seemingly autocratic style of working no one dares question him. And not just that many public sector enterprises have queued up seeking his expertise, the latest in line being the National Highway Authority of India, although he is an aberration among government employees in India: He enjoys breaking rules to get things done. Perhaps the plaque that is in his office summed up Sreedharan, ‘Whatever to be done I do, but in reality, I do not do anything." “That is the way I work, the way I take decisions, the number of hours I utilise. And I have no other distraction except my work. Concentrate on the work, dedication, commitment.” Shreedharan has worked for over 14 years with the Delhi metro, personally overlooking the construction of over 189.63 kilometres with 142 stations. Every Saturday morning Sreedharan dons a white hard hat and inspects parts of Delhi Metro’s citywide expansion. With over 160 trains making nearly 2,400 trips a day and carrying about 1.8 million passengers daily, for Sreedharan Delhi metro project was a personal challenge that he took seriously: every achievement for the metro was a feather in his cap, and every failure was looked by him as his own. Following the collapse of a launching girder lost balance as it was being erected at Zamrudpur, near East of Kailash, which left 6 people dead, Sreedahran offered to resign from his post of MD of Delhi Metro. Chief Minister Shiela Dikshit rejected his resignation saying that the Delhi Metro and the country needed his services. “We respect his sentiments. But we also know that the Delhi Metro and the country need him. Not only he does good work for Delhi but also for the country,” she said. For his services to the nation, which include the construction of the Konkan Railway and the Delhi metro, he was awarded Padma Shri by the government of India in 2001. For a disciplinarian Sreedharan follows a strict routine. A routine he has followed for 10 years. “I come to the office between 8:30-8:45 in the office. I also leave the office by 5:30 and 5:45.” “Within the office there are very regular schedules laid down. What are the meetings that should take place, whom I should meet. These are all very rigidly they are done. And now these things, punctuality is very important. I give lot of importance to punctuality and on Saturdays I keep aside for site visits. So that what are the problems on the sites, what help they need from me. The site visits are not for fact-finding, for witch-hunting. Site visits are mainly to solve the problems on the site and to motivate the people. “That makes lot of difference, you see, people should not be afraid of my visits, my inspections. They should welcome my inspections.” “Of course morning I spent quite enough time on spirituality. One hour, meditation, pranayam,” Sreedharan was quoted by

Reuters

. Following his retirement he plans to spend the rest of his days in his native village in Palakad, Kerala, engaging in spiritual pursuits. “I will go back to my village and pursue things which I could not do so far in my life like reading Srimad Baghvatam, Upanishads and other Vedic literature. I will miss certain things but I will gain certain things. I will miss a good well-oiled organisation. I can give any order and it will get carried out but then it is only external. I will have more internal gains—more peace of mind and better health,” he told

Business Standard

. Sreedharan was succeeded by Mangu Singh. Singh, an Indian Railways Service of Engineers (IRSE) officer of the 1981 batch, worked with Sreedharan on the Kolkata Metro project. He has been associated with the Delhi Metro since its inception.

[/caption] And he likes to do things his way. Unlike most bureaucrats and technocrats working for the government, Shreedharan doesn’t take ’no’ for an answer. When he set out to build an information technology park outside Delhi, the requisite permissions were slow in coming. Sreedharan simply went ahead. Completed in 2005, the IT park now is thriving and houses several high-profile Indian companies, including Genpact, says

Businessweek

. “All the works which the civic authorities are required to do, we did it ourselves without waiting for them,” Sreedharan told

Reuters

. On Saturday, December 31, 2011, Sreedharan called it quits. At 79 he was the oldest technocrat working for the Government of India. Sreedharan officially retired in 1990 but was asked to report back to build the Konkan Railway, before being asked to take over the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation. “For us, time is money. We know that each day is so important and we can’t allow one day to waste,” Shreedharan was quoted by

Reuters

, when asked about Delhi Metro’s success. Perhaps it was this no-nonsense attitude to delivery and sticking to deadlines that led the Delhi government to give him a free hand in to hiring people, deciding on tenders and controlling funds. “The project report of Phase-I envisaged completion in 10 years but one of the first decisions I took was to finish it in seven years. We did it in seven years and three months. There was a query from the government of India, asking why the damn hurry? The money they would have released in 10 years had to be released in seven years. But when they saw the result, they started having confidence and we were able to get what we wanted,” Sreedharan had told

Business Standard

last year. Everyday with the Delhi Metro Sreedharan reminded himself and his employees of his tough deadlines. His desk had a digital clock that counted down the days before the next line must be completed. Similar clocks are found throughout Delhi Metro’s offices and construction sites. His appreciation for punctuality is evident in the way the Delhi Metro functions. Trains run at an interval of 2 minutes 30 seconds between trains at peak frequency at over 90 per cent efficiency when it comes to keeping time. It’s difficult to escape criticism in India, especially if you don’t toe a politician’s line. But even with his seemingly autocratic style of working no one dares question him. And not just that many public sector enterprises have queued up seeking his expertise, the latest in line being the National Highway Authority of India, although he is an aberration among government employees in India: He enjoys breaking rules to get things done. Perhaps the plaque that is in his office summed up Sreedharan, ‘Whatever to be done I do, but in reality, I do not do anything." “That is the way I work, the way I take decisions, the number of hours I utilise. And I have no other distraction except my work. Concentrate on the work, dedication, commitment.” Shreedharan has worked for over 14 years with the Delhi metro, personally overlooking the construction of over 189.63 kilometres with 142 stations. Every Saturday morning Sreedharan dons a white hard hat and inspects parts of Delhi Metro’s citywide expansion. With over 160 trains making nearly 2,400 trips a day and carrying about 1.8 million passengers daily, for Sreedharan Delhi metro project was a personal challenge that he took seriously: every achievement for the metro was a feather in his cap, and every failure was looked by him as his own. Following the collapse of a launching girder lost balance as it was being erected at Zamrudpur, near East of Kailash, which left 6 people dead, Sreedahran offered to resign from his post of MD of Delhi Metro. Chief Minister Shiela Dikshit rejected his resignation saying that the Delhi Metro and the country needed his services. “We respect his sentiments. But we also know that the Delhi Metro and the country need him. Not only he does good work for Delhi but also for the country,” she said. For his services to the nation, which include the construction of the Konkan Railway and the Delhi metro, he was awarded Padma Shri by the government of India in 2001. For a disciplinarian Sreedharan follows a strict routine. A routine he has followed for 10 years. “I come to the office between 8:30-8:45 in the office. I also leave the office by 5:30 and 5:45.” “Within the office there are very regular schedules laid down. What are the meetings that should take place, whom I should meet. These are all very rigidly they are done. And now these things, punctuality is very important. I give lot of importance to punctuality and on Saturdays I keep aside for site visits. So that what are the problems on the sites, what help they need from me. The site visits are not for fact-finding, for witch-hunting. Site visits are mainly to solve the problems on the site and to motivate the people. “That makes lot of difference, you see, people should not be afraid of my visits, my inspections. They should welcome my inspections.” “Of course morning I spent quite enough time on spirituality. One hour, meditation, pranayam,” Sreedharan was quoted by

Reuters

. Following his retirement he plans to spend the rest of his days in his native village in Palakad, Kerala, engaging in spiritual pursuits. “I will go back to my village and pursue things which I could not do so far in my life like reading Srimad Baghvatam, Upanishads and other Vedic literature. I will miss certain things but I will gain certain things. I will miss a good well-oiled organisation. I can give any order and it will get carried out but then it is only external. I will have more internal gains—more peace of mind and better health,” he told

Business Standard

. Sreedharan was succeeded by Mangu Singh. Singh, an Indian Railways Service of Engineers (IRSE) officer of the 1981 batch, worked with Sreedharan on the Kolkata Metro project. He has been associated with the Delhi Metro since its inception.

Metro man retires after 14 years of unmatched efficiency

FP Staff

• January 5, 2012, 11:22:43 IST

On Saturday, December 31, 2011, E Sreedharan of the Delhi Metro Corporation retired. A strict disciplinarian, Sreedharan ensured that Delhi Metro delivered efficiency India had never seen before.

Advertisement

)

End of Article