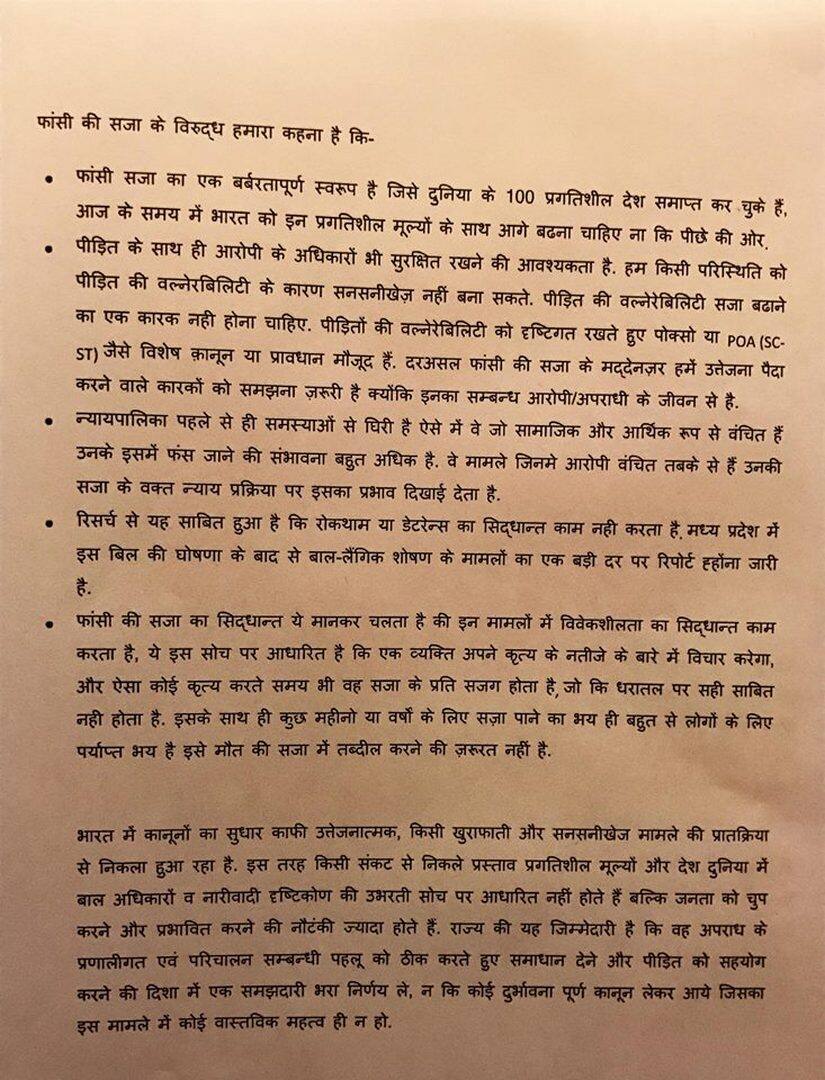

In 2017, the Madhya Pradesh Assembly unanimously passed a Bill introducing the death penalty for those found guilty of raping minors aged 12 years or less. This came a week after the state cabinet approved amendments to the Public Safety Bill. The Bill proposes death penalty or a minimum of 14-years’ rigorous imprisonment, or life imprisonment till death for those convicted of raping minors. After an 8-year-old girl was raped in Mandsaur on 26 June, Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan promised the death penalty for the accused. “These beasts are a burden on the earth. They do not deserve to live,” he told reporters at his Bhopal residence a day after the incident. However, some people in Madhya Pradesh are opposed to the idea of death penalty for such crimes, and fear that it will have disturbing implications. One of these fears is that the existence of the death penalty may lead the perpetrator to kill the victim, in an effort to erase evidence. Another reason cited is that a penalty like this one acts as a distraction from the need to undertake structural changes and to put in place mechanisms to prevent such incidents in the first place. Sachin Jain of Vikas Samvad, a research and policy advocacy organisation based in Bhopal spent the last six months collecting National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data on crimes against children in India from 2000 to 2016. He shared the following findings concerning Madhya Pradesh: During this period, the number of crimes against children grew from 1,425 to 13,746 (865 percent) in Madhya Pradesh. Out of the 153,701 cases of rape of children and sexual abuse registered across the country, 23,659 were from Madhya Pradesh. As many as 249,383 children were kidnapped in India and Madhya Pradesh accounted for 23,564 (9 percent) of these. The number of cases of crimes against children which were pending in courts in Madhya Pradesh stood at 2,065 in 2001. In 16 years, this number has risen to 31,392. [caption id=“attachment_4649621” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  A candlelight march seeking justice in the Mandsaur case. Pallavi Rebbapragada/Firstpost[/caption] “For the year 2018-19, the government of Madhya Pradesh made a total allocation of Rs 90.61 crore for 3.2 crore children, which amounts to Rs 28 per child per year. Of this, Rs. 67.76 crore has been provided for the Integrated Child Protection Scheme, a government programme aimed at ensuring the safety of children. From this, 27.09 crore (40 percent) goes towards salaries and wages,” stated Jain, and added that a review of MP’s budget for 2018-19 suggests that only 0.044 percent of the total budget of Rs 2.05 lakh crore has been provided for child protection. “Even after looking at these findings, we feel that only about 5 percent cases of sexual abuse are being reported. The one way to bring about a seriousness on the issue of crimes against children is to make protection of women and women and children a central indicator of socio-economic development. Political parties, the Parliament, Assemblies and media institutions should conduct special training programs on child protection and gender,” Jain said. Rekha Shridhar, a member of the Child Welfare Commitee in Bhopal, said, “Instead of asking for a law that eliminates the criminal, does it not make sense to redouble efforts to weed out persistent errors from the system?” She added, “Time and again, we have faced a situation wherein the police station refused to register FIRs even in cases that fall under the POCSO Act.” Shridhar cites a case she encountered in 2015 involving a girl from Vidisha who was being trafficked by her family. It took Shridhar 15 days and appeals to state authorities at all levels to register an FIR at Kamla Nagar Police Station, Bhopal. Firstpost reached out to organisations involved in advocacy on child safety in Madhya Pradesh to understand if the introduction of death penalty and the demands for justice by civil society are enough. Devendra Gupta works at a shelter home for over 200 underprivileged children run by a charitable organisation Nitya Seva Society in Gandhinagar. He told Firstpost children are rescued from bus stands, railway stations or come from broken families. “One district has only one Child Welfare Committee, which functions as a court and assigns the child to an orphanage or a shelter home. The lack of cooperation from the side of the police becomes evident when FIRs for missing children take three to four days to get registered.” In agreement with Gupta’s views is Smriti Shukla, who works with the Saathiya Sanstha, a community welfare group working on training and capacity building in Betul, Bhopal, Sehore and Shajapur. She said, “In Sehore, I have seen that women who complain of sexual violence, especially in marriages, are asked to go home and resolve matters with their partners. Gender sensitisation of women police staff towards dealing with women and girls must become a priority.” Javed Anis, who addressed the UN Forum on Minority Issues in Geneva in 2013, described the call for death penalty as a purely populist move. Anis states that even a social problem like rape cannot be discussed openly in government schools of a big city like Bhopal. “The teaching staff at government schools must be sensitised towards discussing subjects pertaining to sexual abuse with children,” he stated. But teachers, who are the primary non-family point of contact for children, have problems of their own. A report tabled in Parliament in 2016 showed that more than 17,000 schools in Madhya Pradesh had only one teacher and the state accounted for one-sixth of ‘single-teacher’ schools in India. Anis said that temporary staff members, who are paid Rs 10,000 to Rs 15,000 a month, exceed the permanent staff. They are burdened with additional work like mid-day meals and even getting underprivileged children admitted to private schools in compliance with the Right to Education Act. He added, “The other aspect is that of children dropping out of school, inhaling cheap chemical drugs like tyre puncture solution, and subsequently getting drawn to crime.” People who know the family of Irfan, the prime accused in the Mandsaur rape case of 26 June, told Firstpost he had a history of alcohol abuse. In 2014, a one stop crisis centre was opened in Bhopal. Here, survivors of sexual abuse can register an FIR, get medical treatment, counselling and legal aid. The centre was opened after an episode on rape on the television show Satyamev Jayate. Two years later, the Women and Child Development (WCD) department set up its own centre adjacent to it. The two are a part of the complex of JP Hospital. The government establishments came to be known as Sakhi Centres. As on 1 March, 2018, 17 such centres have been set up: One each in Indore, Bhopal, Burhanpur, Chhindwara, Dewas, Gwalior, Hoshangabad, Jabalpur, Katni, Khandwa, Morena, Ratlam, Sagar, Rewa, Sagar, Satna, Shadol, Singrauli and Ujjain. Speaking on these centres, Neelam Tiwari, legal rights awareness coordinator at the Samhita Development Network, said, “The initiative is unprecedented, but there are two issues that must be structurally resolved. One is that minors won’t go to a designated centre to report an FIR, in a state of trauma, they will be taken by others to police stations closest to them. Secondly, the woman or parent of a minor victim might not want to speak in public about the incident of rape. They may fear losing anonymity by going to a place designed for crisis cases. Moreover, these centres in large cities like Bhopal and Indore are crowded public platforms.” Indu Pandey, administrator, one stop crisis centre in Indore, said that she doesn’t receive cases pertaining to sexual abuse of children but deals with many cases of marital violence. At a similar centre in Burhanpur, Swabhav Jain, the assistant director, said the same thing. At Ratlam’s one stop crisis centre, District Child Protection Officer RK Mishra said that the possible reason why the centre has not received a single case of sexual abuse of a child till now is that in most such cases the perpetrator is known to the victim and the families don’t want to come forward. “The problem is not in the structure of the institution, but the mentality that prompts people to first reach out to the police, and the lack of awareness of the POCSO Act. In order to educate children, we stream films on the POCSO Act in schools and put up hoardings. But unless parents and communities are able to discuss the topic of rape openly, it will be difficult to even quantify the problem,” he explained. In April, members of the Child Rights Alliance (CRA), a group of nearly 50 people (NGOs and independent social activists) from Bhopal submitted a memorandum to Governor Anandiben Patel demanding repealing of the Public Safety Bill. The memorandum submitted by the Child Rights Alliance to the Madhya Pradesh governor states that 100 countries have banned death penalty and that such a rule will burden courts and make it harder for those from economically impoverished backgrounds to defend themselves in court. The members of the alliance have emphasised on the possibility of a victim of sexual abuse being killed by the perpetrator, if the punishment for rape and murder is the same. Anjali Noronha, who has been working for 35 years with Eklavya, an education organisation, is a part of the alliance. Following is a copy of the memorandum she shared with Firstpost: [caption id=“attachment_4649671” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  The memorandum by Child Rights Alliance. Pallavi Rebbapragada/Firstpost[/caption] “Imposing death penalty increases the possibility of the criminal killing the victim to erase evidence. The POCSO Act has been amended to include the death penalty. There was already punishment up to life imprisonment for penetrative and aggravated sexual assault in the provisions of the POCSO Act. The POCSO Act already had stringent punishment for molestation and penetrative sex and also protection of child victims from invasive investigative procedures. By imposing death penalty, the entire issue of women and child safety gets diverted to punishment of the criminal, and the vulnerability continues,” said Noronha. The alliance, which also submitted the memorandum to the President Ram Nath Kovind, believes that better implementation of existing laws, improved safety measures, greater awareness and education would go a long way to reduce sex crimes, and that the death penalty would have the opposite effect. This is the second of a two-part series. Read the first part here.

Some people in Madhya Pradesh are opposed to death penalty for crimes such as the Mandsaur rape, and fear that it will have disturbing implications.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)