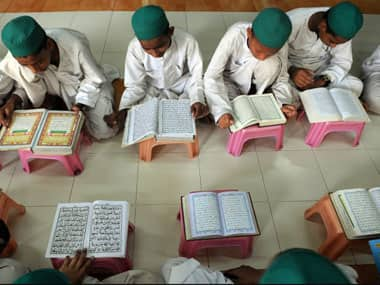

The Maharashtra government’s position that madrasas educating students without teaching them science, mathematics and social studies are non-schools and the children studying there will be considered “out of school” has predictably drawn outrage from the Muslim community. However, many voices from the community candidly admit that the syllabus of the religious seminaries needs to be revised so that poor students of the community can also have access to mainstream, modern education. Maharashtra’s Minority Affairs Minister Eknath Khadse on Thursday said, “Madrasas are giving students education on religion and not giving them formal education. Our Constitution says every child has the right to take formal education, which madrasas do not provide. Thus, madrasa is not a school but a source of religious education. We have asked them to teach students other subjects as well. Otherwise, these madrasas will be considered as non-schools and will not be eligible for government funding.” [caption id=“attachment_2327130” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

Representational image. AFP[/caption] In addition, around one lakh Muslim students would me marked “out of school” as the state’s school education department, which will conduct a survey to determine the number of children being taught at religious seminaries, has been asked by the minority affairs department to do the same if the madrasas do not follow a “proper academic curriculum”. Arshad Alam, assistant professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) who has researched on madrasas and has authored ‘Inside a Madrasa: Knowledge, Power and Islamic Identity in India’, described the government’s move “absurd” but admitted that there is an urgent need of completely overhauling the madrasas. “The minister’s statement is absurd and declaring students studying in theological madrasas ‘out of school’ will be like playing with the educational future of Muslim children. But at the same time, there is an urgent need of completely overhauling these madrasas,” he told Firstpost. Explaining that “students studying there have a bleak future because these institutions do not equip them skills required to take advantage of opportunities available in the modern world”. “Secular and modern” education should be introduced in madrasas if the community wants its poor students to compete in this competitive era, he added. Alam feels that the religious leaders of the community, who consider themselves custodians of Islam and oppose modernisation of madrasas, need to be challenged. “Our ulemas (religious scholars) argue that studying theology is the only education and any other knowledge is just a skill to validate Islamic teachings. This understanding must go. And it can happen when the community starts questioning the clerics with logic,” he added. Mumtaz Alam Falahi, who studied in a madrasa till Almiyat (equivalent to pre-university) before pursuing graduation in English from IGNOU and doing masters in journalism, argues that “delisting madrasas” is “unconstitutional” and in “violation” of Article 30, which is called a Charter of Education Rights. “Madrasas are administrated by the Article 30. Article 30 mandates that all minorities, whether based on religion or language shall have the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice. It provides absolute right to the minorities that they can establish their own linguistic and religious institutions and at the same time can also claim for government’s grant and aid without any discrimination. Thus, declaring madrasas non-schools if they do not impart formal or modern education and denying its right to claim government aid is unconstitutional and in violation of the said article,” he told Firstpost. He raised doubt over the government’s “serious concern” for a small percentage of students of the Muslim community. “Only 4% Muslim children study at madrasas. I fail to understand why the government is so concerned about them. What about the rest 96% Muslim students?” he asked. Though he also advocates revision of the madrasa syllabus, he refuses to accept that only religious teachings are imparted in these seminaries. “There are several madrasas in the country where students are taught mathematics, science, and social science and language papers like Hindi, English and even Sanskirt in addition to Islamic studies. Such madrasas are affiliated to different central as well as global universities where students pursue higher education. These varsities recognise the certificate issued by them. At Jamiatul Falah in Uttar Pradesh’s Azamgarh district, where I have studied, English, Hindi, science and social studies were compulsory papers till class 10. We were trained there in journalism as well. We had to come up with a magazine, organise lectures and debates on contemporary issues,” added Falahi, who edits an English news portal. But Falahi also accepted that madrasa syllabus needs to be updated and made professional as per the requirement of the day. He said there are few papers in the existing syllabus that are a century old. “Such obsolete subjects should be replaced with the modern one. The syllabus should be designed in such a way that after getting admission in different universities, madarsa students do not feel like aliens. They should have the idea of outer world,” he said and added, “But madrasas cannot be like mainstream schools. Do not forget that they are religious seminaries set up for a specific purpose which cannot and should not be diluted.” Eminent educationist Firoz Bakht Ahmed, who is the grandnephew of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, agrees with Falahi to a great extent. “The Maharashtra government’s diktat is unreasonable and unjustified. Madarsa is a place where children from extremely weak economical background come to study. If the government de-recognise such institutions, where will these poor children go? There are over 600 madrasas in Maharashtra that are affiliated to the state board. These have to follow the government syllabus. Only private madrasas have their own syllabus and they have all the right to frame it as per their own choice. The government must not interfere in the autonomy of Islamic religious institutions. If the government is so serious about madrasas, it should improve the infrastructure of aided seminaries, release and revise the salary of their staff in time,” he told Firstpost. He said the madrasa syllabus should be revised but the reform should not be imposed. There are many madrasas that impart modern education and promote even sports. “Madrasa Jameatul Hidaya at Ramgarh town in Rajasthan is a symbol of liberation from that dogmatic precept that the traditional ulema have always thrived on to present a lopsided view of the Islamic heritage. The seminary happens to be the only madrasa where deeni taleem (religious education) has been perfectly blended with the modern and technically advanced system of education in such a way that the students passing out from there can even join the general institutions. It has computers, electronic labs, cricket, basketball and volleyball teams and debating societies in English and Hindi,” he said adding that this institution is not the only one in this country. There are hundreds of such Islamic seminaries across the country. “Therefore, instead of derecognising of madrasas, the government should make effort to break the common perception that Islamic institutions are ghettoes of antiquity, obscurantism and orthodoxy,” he concluded. M Reyaz, a research scholar at Jamia Millia Islamia, agrees that those madrasas catering to teenagers need to accommodate more of mainstream subjects, but the religious institutions are not homogenous. “The tragedy is most people who speak against madrasas have never actually visited one. While I agree that those madrasas catering to teenagers – middle, high school level – need to accommodate more of mainstream subjects, it should be understood that madrasas are not a homogenous entity. There are many already doing it. Most madrasas cater to poorest people and if it were not for these they would have never got any education,” he told Firstpost. “It is nothing but prejudice to ask how many engineers have come out of madrasas. It is like asking a social science college, why you don’t produce science graduates. Moreover, there are indeed many madrasa graduates who later study in universities to become doctors, teachers and are even working in the IT sector”.

Representational image. AFP[/caption] In addition, around one lakh Muslim students would me marked “out of school” as the state’s school education department, which will conduct a survey to determine the number of children being taught at religious seminaries, has been asked by the minority affairs department to do the same if the madrasas do not follow a “proper academic curriculum”. Arshad Alam, assistant professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) who has researched on madrasas and has authored ‘Inside a Madrasa: Knowledge, Power and Islamic Identity in India’, described the government’s move “absurd” but admitted that there is an urgent need of completely overhauling the madrasas. “The minister’s statement is absurd and declaring students studying in theological madrasas ‘out of school’ will be like playing with the educational future of Muslim children. But at the same time, there is an urgent need of completely overhauling these madrasas,” he told Firstpost. Explaining that “students studying there have a bleak future because these institutions do not equip them skills required to take advantage of opportunities available in the modern world”. “Secular and modern” education should be introduced in madrasas if the community wants its poor students to compete in this competitive era, he added. Alam feels that the religious leaders of the community, who consider themselves custodians of Islam and oppose modernisation of madrasas, need to be challenged. “Our ulemas (religious scholars) argue that studying theology is the only education and any other knowledge is just a skill to validate Islamic teachings. This understanding must go. And it can happen when the community starts questioning the clerics with logic,” he added. Mumtaz Alam Falahi, who studied in a madrasa till Almiyat (equivalent to pre-university) before pursuing graduation in English from IGNOU and doing masters in journalism, argues that “delisting madrasas” is “unconstitutional” and in “violation” of Article 30, which is called a Charter of Education Rights. “Madrasas are administrated by the Article 30. Article 30 mandates that all minorities, whether based on religion or language shall have the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice. It provides absolute right to the minorities that they can establish their own linguistic and religious institutions and at the same time can also claim for government’s grant and aid without any discrimination. Thus, declaring madrasas non-schools if they do not impart formal or modern education and denying its right to claim government aid is unconstitutional and in violation of the said article,” he told Firstpost. He raised doubt over the government’s “serious concern” for a small percentage of students of the Muslim community. “Only 4% Muslim children study at madrasas. I fail to understand why the government is so concerned about them. What about the rest 96% Muslim students?” he asked. Though he also advocates revision of the madrasa syllabus, he refuses to accept that only religious teachings are imparted in these seminaries. “There are several madrasas in the country where students are taught mathematics, science, and social science and language papers like Hindi, English and even Sanskirt in addition to Islamic studies. Such madrasas are affiliated to different central as well as global universities where students pursue higher education. These varsities recognise the certificate issued by them. At Jamiatul Falah in Uttar Pradesh’s Azamgarh district, where I have studied, English, Hindi, science and social studies were compulsory papers till class 10. We were trained there in journalism as well. We had to come up with a magazine, organise lectures and debates on contemporary issues,” added Falahi, who edits an English news portal. But Falahi also accepted that madrasa syllabus needs to be updated and made professional as per the requirement of the day. He said there are few papers in the existing syllabus that are a century old. “Such obsolete subjects should be replaced with the modern one. The syllabus should be designed in such a way that after getting admission in different universities, madarsa students do not feel like aliens. They should have the idea of outer world,” he said and added, “But madrasas cannot be like mainstream schools. Do not forget that they are religious seminaries set up for a specific purpose which cannot and should not be diluted.” Eminent educationist Firoz Bakht Ahmed, who is the grandnephew of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, agrees with Falahi to a great extent. “The Maharashtra government’s diktat is unreasonable and unjustified. Madarsa is a place where children from extremely weak economical background come to study. If the government de-recognise such institutions, where will these poor children go? There are over 600 madrasas in Maharashtra that are affiliated to the state board. These have to follow the government syllabus. Only private madrasas have their own syllabus and they have all the right to frame it as per their own choice. The government must not interfere in the autonomy of Islamic religious institutions. If the government is so serious about madrasas, it should improve the infrastructure of aided seminaries, release and revise the salary of their staff in time,” he told Firstpost. He said the madrasa syllabus should be revised but the reform should not be imposed. There are many madrasas that impart modern education and promote even sports. “Madrasa Jameatul Hidaya at Ramgarh town in Rajasthan is a symbol of liberation from that dogmatic precept that the traditional ulema have always thrived on to present a lopsided view of the Islamic heritage. The seminary happens to be the only madrasa where deeni taleem (religious education) has been perfectly blended with the modern and technically advanced system of education in such a way that the students passing out from there can even join the general institutions. It has computers, electronic labs, cricket, basketball and volleyball teams and debating societies in English and Hindi,” he said adding that this institution is not the only one in this country. There are hundreds of such Islamic seminaries across the country. “Therefore, instead of derecognising of madrasas, the government should make effort to break the common perception that Islamic institutions are ghettoes of antiquity, obscurantism and orthodoxy,” he concluded. M Reyaz, a research scholar at Jamia Millia Islamia, agrees that those madrasas catering to teenagers need to accommodate more of mainstream subjects, but the religious institutions are not homogenous. “The tragedy is most people who speak against madrasas have never actually visited one. While I agree that those madrasas catering to teenagers – middle, high school level – need to accommodate more of mainstream subjects, it should be understood that madrasas are not a homogenous entity. There are many already doing it. Most madrasas cater to poorest people and if it were not for these they would have never got any education,” he told Firstpost. “It is nothing but prejudice to ask how many engineers have come out of madrasas. It is like asking a social science college, why you don’t produce science graduates. Moreover, there are indeed many madrasa graduates who later study in universities to become doctors, teachers and are even working in the IT sector”.

Maharashtra govt’s stand on madrasas reeks of ignorance, but seminaries need to modernise too

Tarique Anwar

• July 4, 2015, 13:30:52 IST

The Maharashtra government’s position on madrasas being non-schools is ignorant however the syllabus of the religious seminaries needs to be revised so that poor students can have access to modern education.

Advertisement

)

End of Article