Editor’s Note: This article first appeared in Issue 12 of Firstpost print. When Vineet Chauhan graduated from Neelkanth Institute of Engineering and Technology, Meerut, with a B.Tech in 2016, he did not think that he would be looking forward so keenly to the 2019 general elections. Working for the local Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) candidate — his family has long been a supporter of the party — in his village in western Uttar Pradesh’s Kairana parliamentary constituency has given a bit of structure to his days, which are otherwise spent in some pursuit of meaning. “I don’t know what it is to be busy. Outside of my student life, I have never known what it is to have important work to do,” says 25-year-old Chauhan who has been looking for a job, but with no luck. [caption id=“attachment_6435801” align=“alignleft” width=“371”]

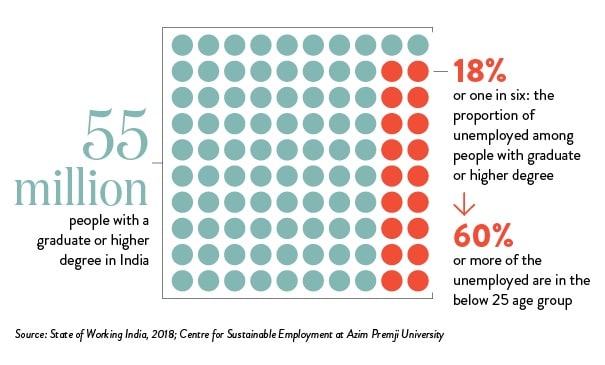

Youth at a job fair. File photo[/caption] Everyone from Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Congress president Rahul Gandhi has been working hard to reach out to India’s first-time voters, promising employment and entrepreneurial opportunity. But underemployed, under-educated, India’s Timepass Generation has become cynical about politics and is putting its faith in TikTok and tequila shots. There are 55 million people in the labour force with a graduate or higher degree, according to the State of Working India, 2018 report, released by the Centre for Sustainable Employment at Azim Premji University. Almost one in six is unemployed and Chauhan falls in this category. The facts, terrifying in their starkness, just keep piling up. Unemployment in the category of people with a graduate or higher degree is three times the national average. And more than 60 percent of the unemployed are in the 15-25 age group. The problem is as much the unavailability of jobs as the kind of employment opportunities that this workforce feels are commensurate with their skills and degrees. Chauhan has travelled from Meerut to Delhi to Chandigarh in search of a job, but at best, he was offered entry-level positions at private companies at a starting salary of Rs 6,000 to Rs 8,000. His family spent upwards of Rs 5 lakh on his graduation. “Everyone keeps asking me, ‘What are you doing?’ Lage hue hain bas (I’m trying),” he says. In 2004-05, Craig Jeffrey, director of the Australia India Institute in Melbourne, worked with a large number of young people “who had acquired qualifications but been unable to secure work and lacked the skills to start businesses or find lucrative jobs in the private sector”. Jeffrey, in an email interview to Firstpost, describes these young people as being in a limbo, “stuck somehow between the modern and traditional, urban and rural, childhood and adulthood”. During the course of his research, he came across one word over and over again, “timepass”. It became the title of his book, Timepass: Youth, Class and the Politics of Waiting in India. At 46, Vijendra Singh is a little older than the people Jeffrey would have interviewed for his book, but he understands the phenomenon all too well. Only he doesn’t call it timepass. “Samay pathra sa gaya hai,” he says, the closest approximation of which is that time has fossilised for him. He holds a diploma in engineering but never got down to looking for work as the family came into money during the property boom in Ghaziabad. “We did the usual things: build a big house, buy big cars. Then money ran out.” ALSO READ: Lack of jobs is a very real challenge Singh’s day begins at dawn with a game of badminton with other men of his village. “Then we sit and chat.” Politics? “Sure,” he chuckles. The conversation usually centres on who drank what last night, who will drink what tonight. “Then we nap. Then we go for a walk. Then people assemble and start drinking. I realised later in life that youngsters need jobs to keep them grounded. It gives you your identity.”

![image-2019-04-12 (2)]()

Singh is a native of Sadopur village, in Ghaziabad. He and neighbour Jagbir Singh run the Ambition Library, which is akin to a study centre for the local youth. The idea was to provide a space for youngsters to prepare for government exams rather than while away time in the village. “A lot of people active in student political groups come from this area. They would pile these boys up in jeeps every time they needed some muscle flexing in Delhi. The centre is meant as an alternative to all of this,” says Vijendra. Girls and boys from various academic backgrounds come to the centre. From MBAs to B.Com graduates, they are all there, everyday, in a bid to crack government service exams because that is where the real job security lies. “I am an MBA and even worked in a private firm for some time. But I was being paid a pittance and the workload was too much,” says Bhim Singh Nagar. He is hoping to clear the SSC exams in June. “The truth of the matter is that even if you are a Group D employee, it is better than earning ₹1 lakh in a private company,” says Aakash Nagar (no relation to Bhim Singh). Aakash has a B.Tech degree from the Hi-Tech Institute of Engineering and Technology, Ghaziabad. He is a remarkably self-aware 22-year-old with strong views on the education system. “Quality education in this country is of very low quality.” He is under no illusion about the value of his engineering degree or what he may have learnt in the classroom. “There is no push on understanding but rather about getting the degree. And colleges don’t help you in getting a job.” The engineering college boom in India was triggered by government education loans. The proliferation of institutes with next to no quality control has long been an area of concern. According to the National Employability Report – Engineers, 2019, prepared by Aspiring Minds, only 3.84 per cent of India’s engineers are employable in software-related jobs. And while India may be under the impression that Silicon Valley runs on engineers trained here, the US has a much higher proportion of engineers, almost four times, who have good programming skills. MBAs are not far behind. A study by ASSOCHAM had found that only 7 per cent of India’s business school graduates are employable. The Annual State of Education Report, 2017, established that quality of education in the 14-18 age group of Indian students remains a matter of grave concern. “We have generations that are growing up into an aspirational life but we are not able to guarantee a standard of living for them. Be it school level or higher, we are not doing well. Our failure to provide for the youth of the country can lead to social unrest. We may as well be sitting on a ticking time bomb,” says professor Amit Basole, an economist at the Azim Premji University. By 2020, India is expected to be the youngest nation in the world with half of its population under the age of 25. It is this section that will shape the future of the country. But their own future remains uncertain. Pushpendra Singh, a 29-year-old with an M.Com degree had made up his mind in school itself that he wanted a “private” job. He comes from a family of farmers and, while they were never poor, money was always a concern. He ticked all the boxes he thought were needed to do well: a degree, an additional skill course. But that wasn’t enough. “I was working in a sugar factory in Nagpur at a salary of ₹15,000 out of which rent alone was ₹5,000. I wasn’t saving any money and eventually had to return home.” Home is a village some distance away from Bareilly. He apologises for the way he speaks, a patina of local dialect with Hindi thrown in. “I used to speak like city people when I studied in Bareilly. Now, I talk like everyone else in the village,” he says ruefully. Singh understands the concept of timepass very well though he says not all days are like that. “There are seasons when we are busy and then there are seasons when we are not.” Playing cards and going to neighbouring villages to meet relatives are the two principal ways in which he and other young men in the locality spend their time. “The elders taunt us, ask us why are we not working, why are we doing tapribaazi (goofing off). It’s humiliating but I don’t have an answer for it.” An increasingly dissatisfied educated youth population will have a big impact on the social, economic and religious fabric of a society like India’s. The recent agitation by Jats and Patidars, traditionally well-off communities, for reservation can be seen through this lens. In the Ambition Library centre, for instance, there is deep resentment against caste-based reservation with students feeling that it should be stopped once a family has managed to lift itself up by the bootstraps. “We don’t get a foot in the door otherwise,” says Aakash. Unemployment and underemployment, especially after the NSSO data leak, had “the potential to be the biggest electoral issue for these elections but neither the government nor the Opposition is interested in highlighting it. The youth of the country, on the other hand, feels completely abandoned,” says Anupam (who goes by only one name) of Swaraj India. The party has started a Yuva Halla Bol campaign against the SSC paper leak that also works with young people on issues of unemployment. While unemployment has become a simmering concern, Anupam is right when he says that the mainstream political parties aren’t really addressing it. The Congress in its manifesto has promised a new ministry of industry, services and employment apart from filling in all the 20 lakh vacancies in government jobs. The BJP has not made any concrete claims, for its part, but has vowed to increase investment for job creation. But how will the issue end up impacting voting behaviour of the unemployed youth in the coming weeks? Voting behaviour still seems to be dictated by caste concerns rather than economic ones. Most of the people interviewed by Firstpost did not seem to hold the government or any party directly responsible for the mess they find themselves in.

“In the current cycle of elections, the unemployment issue has manifested itself in rallies for reservation. Political mobilisation still follows caste lines,” says Basole. Lack of employment can bring about a strong sense of dislocation as well as identity crises, particularly in a society as hierarchical as India where secure, sustained employment is often seen as a ticket out of penury. Increasingly, this has also started impacting the wedding prospects of young men, with most families and girls preferring a stable government job as opposed to farming or even private sector employment. Faced with the lack of all these factors, can caste and religious identities start taking hold, leading to unrest? ‘Youth bulge’ and its impact on society has been a subject of much research with one extreme view, as posited by German demographer Gunnar Heinsohn, stating that there are links between violence and an increasingly young population. This theory, however, has been contested. Professor Jeffrey feels that there is also evidence to show that “educated unemployed or underemployed young people can play constructive roles…the world has changed so much since middle-aged Indians were growing up. In this context, young people in their twenties often play a key role as a type of ‘intermediary generation.’ They advise their younger peers on issues such as career choices, education, health care, relationships…young people act under the radar to assist youth in their neighbourhoods”. A prime example of this would be someone like Ashish Patwa, a resident of Gorakhpur. Patwa holds several degrees (“BA, MA, B.Ed, I have done it all”) but works in his father’s cotton store as he says he never had good enough grades to really qualify for anything. “I advise young men on career options and choices quite a bit. My degrees give me a certain standing in society and I do feel that they have expanded my horizon.” The leaked NSSO data reveals that unemployment in India was at a 45- year high of 6.1 per cent in 2017-18. In such a scenario, Vineet Chauhan is hoping that his involvement with the local politician may lead to employment opportunities before existential crisis swallows him whole. “Everyone needs astitva (a sense of being). Without work, life is meaningless.”

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)