The COVID-19 pandemic has shifted policy focus to health in an unprecedented manner. Expenditures on health systems and developing targeted health care policies are beginning to get their due in policy discussions as well, and with good reason. There is a broad consensus among multilateral institutions (e.g. the

World Bank

) as well as researchers and activists, that the development of human capital (especially via investment in health) is as critical for a country’s growth as financial or physical capital. Intuitively, a healthy population can enhance the skill and productivity of a nation. However, it is pertinent to ask how we measure health. Measuring health at one point of time can be challenging, although researchers usually measure quantitative changes in health in terms of the height and weight of an individual (i.e. physical development). On the basis of these components, the various measures are summarised as stunting, wasting and underweight. Stunting (height for age) measures the cumulative deprivation from birth, wasting (weight for height) is a measure of short-term nutritional deficiency and underweight (weight for age) measures both stunting as well as wasting.

A recent study

by the World Bank finds that stunting may actually have a huge economic cost. Their findings suggest that stunting in early childhood leads to developmental deficiency and thus lower productivity. The data on stunting, wasting and underweight are usually collected from

Demographic and Health Surveys

, a collection of nearly 400 surveys across 90 countries. In India, these data are collected under the aegis of the National Family and Health Survey (

NFHS

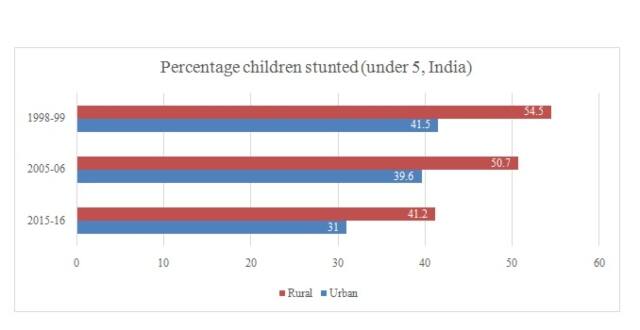

), which is a nationally representative dataset covering health, fertility, and other characteristics in rural and urban India. The graph below shows the proportion of children who are stunted in various rounds of NFHS, separately for rural and urban India. Overall, it would appear that child stunting is on the decline in both urban and rural areas over the past two decades. There have been many associations drawn between protective factors for a child’s nutritional status, including the mother’s decision-making

autonomy

, household wealth, and

others

. [caption id=“attachment_9500801” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Source: StatCompiler, DHS[/caption] Most recent data from the NFHS-5 (2018-19) has been released for phase I for 22 states. The report shows that for most of the states the stunting rates have actually increased. According to

the report

, 16 states out of 22 states have recorded an increase in the wasting and underweight rates which represents long-term deprivation. Overall, as the below figure shows, there is a 1 percent increase in stunting on average across the states for which data was released. There are similar, marginal increases reported if we consider all-India average measures for underweight, wasting, and severe wasting.

Source: StatCompiler, DHS[/caption] Most recent data from the NFHS-5 (2018-19) has been released for phase I for 22 states. The report shows that for most of the states the stunting rates have actually increased. According to

the report

, 16 states out of 22 states have recorded an increase in the wasting and underweight rates which represents long-term deprivation. Overall, as the below figure shows, there is a 1 percent increase in stunting on average across the states for which data was released. There are similar, marginal increases reported if we consider all-India average measures for underweight, wasting, and severe wasting.

| India | China | |

|---|---|---|

| Infant Mortality Rate | 47 | 13 |

| Under 5 Mortality Rate | 61 | 15 |

| Underweight | 43 | 4 |

| Stunted | 48 | 10 |

| Public expenditure on health as a proportion of total health expenditure(%) | 1.2 | 2.7 |

Source: Dreze and Sen (2013) This low spending on health has made our country more vulnerable to external shocks arising from poor health. In spite of the various efforts of the government, there have been setbacks on the nutritional front as can be seen from the NFHS-5. Even as discussions on capitalising on India’s demographic dividend continue, the importance of investing in child health cannot be underscored enough. This can be done by strengthening the already existing delivery mechanisms such as the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and Mid-Day Meal schemes. Both these programmes have an immense capacity to make an impact on nutrition and child health. In recent years, however, there has been a fall in the public expenditure as a percentage of GDP on both these schemes. Besides, the pandemic poses further challenges, especially for vulnerable groups and populations that are hard to reach. The biggest challenge today is to consolidate existing programmes of work, devoting more financial resources, and improving accountability among the public health workers. In a democratic set up such as India, we have all the more reasons to implement and improve the quality of life especially the children who are the future citizens of the country. Chakraborty is a PhD Scholar in Economics at North Bengal University and Independent Researcher at Monk Prayogshala, Mumbai. Tagat is with the Department of Economics at Monk Prayogshala, Mumbai.

)