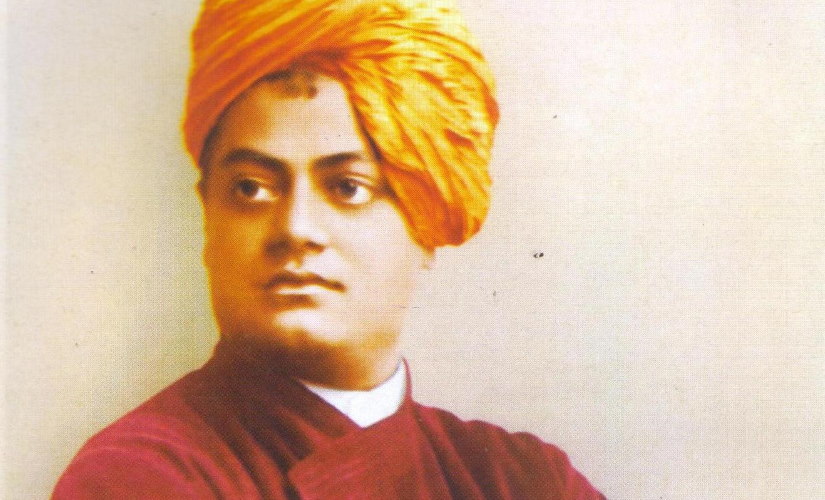

Sometimes, a long walk is all it takes to clear the mind. A few thousand miles across India and a myriad experiences later, I can attest to that. I began walking in 1991 from Bombay. I spent about two years on my journey across India — though not all of it exclusively on foot. Almost 30 years later, I find myself in the unlikely position of being able to give a theological lesson to the Bharatiya Janata Party, the ruling party in India. In 1991, I was a young sub-editor at the Times of India. I showed promise and perhaps could have made a career there. The trouble was, journalism did not interest me. The breathless coverage of interminable political wrangles and the low quality of intellectual discourse dismayed me. Naked political ambition and public immorality of political leaders was analysed, dissected and sought to be understood, “normalising” it in the pages of newspapers. The national resolve I found in reading Nehru, Gandhi or even business leaders such as the Tatas and Birlas was completely missing. The Armed Forces interested me, but I was afraid I could find the discipline constricting. I was a young “rebel”, and I guess I badly needed heroes. In Vivekananda, I found mine. I bought and read his complete works, though haphazardly. [caption id=“attachment_7901121” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Swami Vivekananda. Image via WikimediaCommons[/caption] A few months after I began walking, I became a sadhu of the Vairagi sect. The man who inspired me to do so was the Swami, who was certainly the first English-educated man to study all the main Hindu scriptures in Sanskrit. More so, his intellect and training enabled him to synthesise their teachings into a cogent narrative that could be understood by the layman. He made the scriptures accessible to ordinary people like me. Ironically, if Swami Vivekananda were alive today, he would completely disapprove of Hindutva (Hinduness), or at least the BJP’s interpretation of it. Vivekananda was an Advaitin, or a practitioner of a “monistic” system of philosophy (espousing Oneness) that does not believe in idols, formal worship, outer marks or objects of piety. He declares again and again that the goal of Hinduism is self-realisation, or the first-hand experience of the divine. “The Hindu religion does not consist in struggles and attempts to believe a doctrine or dogma… but in being and becoming,” he told his Chicago audience in 1893. It is doubtful that he would have favoured a Rama temple at Ayodhya. It is true Vivekananda was fiercely proud of Hinduism but it was not of its superstitions or regressive practices. In fact, he was part of the Bengal Renaissance of the 1800s which began with the Brahmo Samaj and reached back into Hindu scripture for support to combat superstition and backward practices like sati and dowry. The Swami was deeply interested in the sciences and mathematics. “Science,” he declared during the same address, “is nothing but the finding of unity.” He also made the momentous claim that the goal of physics, for instance, was to discover “one energy of which all others are but manifestations.” During subsequent visits, the Swami met the great inventor and mathematician Nikola Tesla in an attempt to prove Advaita (or non-dualism) mathematically. “Mr Tesla thinks he can demonstrate mathematically that force and matter are reducible to potential energy. I am to go and see him next week to get mathematical demonstration. (If he is able to do so) Vedantic cosmology will be placed on the surest of foundations,” Vivekananda wrote to a British admirer late in 1895. The attempt failed because, though Tesla grasped that mass must decrease as speed increased, he thought the one “converted” into the other, instead of both being identical in some unknown way, as different expressions of one reality. It was not until Albert Einstein’s paper on relativity in 1905 that this startling concept found scientific expression. In Hinduism it was spirituality and metaphysics the Swami celebrated. Crucially, Vivekananda’s guru, Ramakrishna, whom the Swami worshipped as God Incarnate, openly declared that all revealed religions such as Islam and Christianity were true, and “valid” — something that is diametrically opposed to Hindutva. Guru Ramakrishna’s stand on the validity of all religions is a theme that runs through Indian history. But Ramakrishna reformulated the idea in a unique way. One was in the “globalism” he brought into it. Ramakrishna trained Vivekananda, beginning from when he was a young student, with the express mission to disseminate his teachings to the whole world. So Ramakrishna’s audience was not just Indian, or Hindu alone. The second point of his Guru Ramakrishna’s uniqueness lay in how arrived at his notion of the “validity” of all religions. He did this through personal “sadhana” (or religious effort) prescribed by religions other than Hinduism. He declared that all religions lead to the same God. Ramakrishna said he was initiated into Islam in 1866 and prayed to Allah, and gave up visits to his beloved Kali temple. After three days, “I saw the vision of a radiant figure, approaching and merging in me,” he said. It was thought the figure was Prophet Mohammad. Vivekananda shared this global outlook. He was far from regressive. He never wanted to take India back to a “golden age”. He wanted India to instead embrace the scientific future with confidence. In fact, he advised Parsi industrialist JRD Tata — whom he met aboard a ship from Japan to Canada — to set up scientific institutions in India. When Tata wrote to the Swami to propose the Indian Institute of Science, Vivekananda was effusive in praise. “We are not aware of any project at once so opportune and far-reaching… ever mooted in India,” the Swami wrote in an article in his magazine Prabuddha Bharata. In fact, even verses in the Bhagavad Gita, India’s most sacred single text, can be interpreted to mean that all religions are valid as different paths to suit diverse human temperaments. However, it is important to understand how “validity” of all religions differs from “equality” of all religions — a right first legislated by the Americans. The United States only recognises the right to freely practise religion. It does not declare that all religions are valid paths to the same God. Instead, the US Constitution closely holds to “Judeo-Christian” values at its core. The Indian Constitution stuck to India’s civilisational character by choosing not to be “Hindu". It is a matter of historical record that Hindu India gave refuge to all persecuted people in the world, beginning with the Jews, early Christians, Persians, Ahmadiyyas, Bahais and various others, including Tibetans in 1959. After Partition, when over one million died in Hindu-Muslim riots, it would have been far easier to declare India a country for Hindus but this never tempted the founders. Hindu philosophy had its origins in the Vedas, the most authoritative texts in Hinduism. The Puranas, which are the legends of the many Gods in the Indian pantheon, occupy a lower place. The ruling BJP party’s Hindutva ideology is based on one among the many Puranas — Ramayana. By a fortuitous coincidence, on one fine December afternoon in 1991, a few days after I began walking from Bombay, I met LK Advani, then one of only two BJP MPs in the Lok Sabha. He was going in the opposite direction, in his soon to become famous Rath Yatra, which began the BJP’s rise. I was a journalist walking down the lonely state highway with a rucksack on my back. I must have cut a strange figure. I wonder if he remembers me. Advani was keen to impress upon me the crowds he was drawing on his journey to a disputed temple site where the Rama temple once stood. Even he had no clue what a powerful issue he had found. I wished him luck and continued down the state road towards Navsari, Gujarat. After all, I had a mind to clear.

I began walking in 1991 from Bombay. I spent about two years on my journey across India. Almost 30 years later, I find myself in the unlikely position of being able to give a theological lesson to the Bharatiya Janata Party, the ruling party in India.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)