As reports of

Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman’s capture

by Pakistan appeared to be true on Wednesday, confusion over which side struck which aircraft gave way to a show of solidarity and hopes of a de-escalation of tension between India and Pakistan. Even thought India has

not confirmed the name

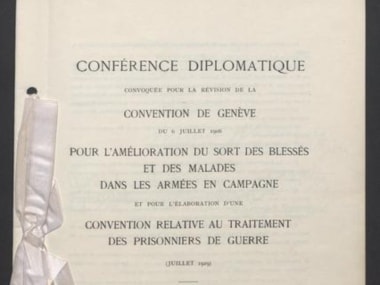

of the missing pilot of the MiG-21 Bison, which went down across the LoC on Wednesday, speculation is rife on the international statutes that require his return soon. The Geneva Conventions: [caption id=“attachment_6171251” align=“alignleft” width=“380”] The cover page of the 1929 Geneva Convention. Wikimedia Commons[/caption] One of the terms most thrown about in this regard, the “Geneva Conventions” are four treaties and three protocols that establish the standards of international law for humanitarian treatment in war. The term “Geneva Convention” refers to the agreements that were arrived at in the aftermath of World War II, in 1949. These agreements were updates of earlier protocols adopted in 1864, 1907 and 1929. As many as 196 countries have given their consent to following the words of the Conventions. The Conventions aim to define the basic rights of both civilians and military personnel who may be taken as wartime prisoners. It also establishes rules to protect those who have been injured, as well as for civilians living or moving in and around a war zone. Importantly for India, the rules of the Conventions apply to times of peace as well. They also apply even if one of the countries has declared a war and the other does not recognise a state of war, if one of them are not a signatory to the Convention and even if one country has occupied another country without facing any armed resistance. In a strongly-worded

statement

, the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) on 27 February had said that it objects to Pakistan’s “vulgar display of an injured personnel of the Indian Air Force”. The MEA mentioned that Pakistan’s conduct was in “violation of all norms of International Humanitarian Law and the Geneva Convention”. Pakistan became a

signatory to the Conventions in 1951

, a year after India did, making it imperative upon both parties to follow the codifications of humanitarian conduct in the Convention. Pakistan army spokesperson Major General Asif Ghafoor tweeted late on Wednesday, seemingly to reassure that the statutes demanding ethical treatment of people captured in conflict are maintained.

The cover page of the 1929 Geneva Convention. Wikimedia Commons[/caption] One of the terms most thrown about in this regard, the “Geneva Conventions” are four treaties and three protocols that establish the standards of international law for humanitarian treatment in war. The term “Geneva Convention” refers to the agreements that were arrived at in the aftermath of World War II, in 1949. These agreements were updates of earlier protocols adopted in 1864, 1907 and 1929. As many as 196 countries have given their consent to following the words of the Conventions. The Conventions aim to define the basic rights of both civilians and military personnel who may be taken as wartime prisoners. It also establishes rules to protect those who have been injured, as well as for civilians living or moving in and around a war zone. Importantly for India, the rules of the Conventions apply to times of peace as well. They also apply even if one of the countries has declared a war and the other does not recognise a state of war, if one of them are not a signatory to the Convention and even if one country has occupied another country without facing any armed resistance. In a strongly-worded

statement

, the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) on 27 February had said that it objects to Pakistan’s “vulgar display of an injured personnel of the Indian Air Force”. The MEA mentioned that Pakistan’s conduct was in “violation of all norms of International Humanitarian Law and the Geneva Convention”. Pakistan became a

signatory to the Conventions in 1951

, a year after India did, making it imperative upon both parties to follow the codifications of humanitarian conduct in the Convention. Pakistan army spokesperson Major General Asif Ghafoor tweeted late on Wednesday, seemingly to reassure that the statutes demanding ethical treatment of people captured in conflict are maintained.

Prisoner of war: While there is little doubt that Abhinandan is governed by the rules of the Geneva Conventions, when it comes to his status as a “prisoner of war”, the codification renders the situation murky. According to the rules, the status of prisoner of war only applies in international armed conflict. The categories of persons entitled to “prisoner of war” status have been broadened and the conditions and places of their captivity gave been more precisely defined, particularly with regard to prisoners of war who are engaged in manual labour, their financial resources, the relief they receive, and the judicial proceedings instituted against them. “Prisoners of war are usually members of the armed forces of one of the parties to a conflict who fall into the hands of the adverse party,” the Conventions state. Such prisoners cannot be prosecuted for taking a direct part in hostilities – something which it is widely speculated the Wing Commander did. He was confirmed to be flying an MiG-21, the same plane that reportedly took down a Pakistani F-16. However, while the Conventions establish the principle that prisoners of war shall be released and repatriated without delay after the end of active hostilities, the question remains as to whether in the lack of clearly defined situation of war, the Wing Commander may be designated as a “prisoner of war”. Nonetheless, the Conventions are firm on the assertion that detention of such a prisoner cannot be by way of punishment, of either the country or the person and must only aim to prevent escalation of the conflict. Notably, the Conventions also mention that the prisoner of war is to be protected against public curiosity, something Pakistan can be accused of flouting, as it has released a video and photographs of the Wing Commander it claims to have taken captive. Hostage: The International Convention against the Taking of Hostages defines the offence as the seizure or detention of a person (the hostage), combined with threatening to kill, to injure or to continue to detain the hostage, in order to compel a third party to do or to abstain from doing any act as an explicit or implicit condition for the release of the hostage. The taking of hostages is considered a grave breach of the Conventions and are bluntly mentioned as “prohibited” in Article 3 of the Fourth Convention. Article 147 of the same Convention reiterates that taking a hostage is a breach similar to that of “willful killing, torture or inhuman treatment, including biological experiments, willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health,” and so on. So Pakistan is unlikely to designate the Wing Commander as a hostage, even though his eventual release will likely be a result of negotiations between India and Pakistan, similar to what is seen when a hostage is set to be freed. International organizations, in particular the United Nations, have also condemned such instances with respect to the Gulf War and conflicts in Cambodia, Chechnya, El Salvador, Kosovo, Middle East, Sierra Leone, Tajikistan and the former Yugoslavia. International armed conflict: The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia had proposed a general definition of international armed conflict. The Tribunal had stated that “an armed conflict exists whenever there is a resort to armed force between States”. This definition has been adopted by other international bodies since then and is considered to be a part of International Humanitarian Law. Rather than “war”, the Geneva Conventions use the term “armed conflict” to highlight that the determination whether an armed conflict exists depends on the prevailing circumstances and not on the subjective views of the parties to the conflict. The threshold for an international armed conflict to be recognised as such is very low, notes the The Rule of Law in Armed Conflict Project. Whenever there is the mobilisation of hostile armed force between two States, there is an international armed conflict. While the Geneva Convention applies both for international and non-international armed conflict, for the latter it stipulates a minimum degree of violence and organisation which it does not for the former. Thus, a skirmish at the border is an international armed conflict, but a scattered group of people fighting with police is not a case of non-international armed conflict. The situation between Pakistan and India is firmly within the category of international armed conflict. War: War is a state of armed conflict between States, governments, societies and informal paramilitary groups, such as mercenaries, insurgents and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence. Because the Geneva Conventions would rather focus on those suffering violence due to a very minimum degree of conflict between States and not on whether the cause to herald the violence has been agreed upon by the two or more parties engaged in violence, it does not go into the definition of war. Follow all the latest updates from the India-Pakistan situation here

)