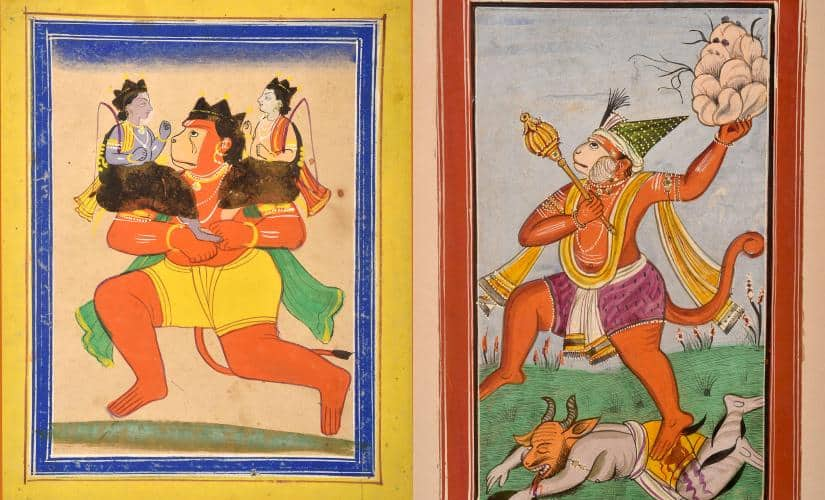

In Tulsidas’ Ramcharitmanas, Hanuman says to Ram, “When I know who I am, you and I are one.” Last week, the Uttar Pradesh chief minister Yogi Adityanath set both heads and eyes rolling when he claimed that Hanuman was a Dalit. Since then, criticism has been levelled against Adityanath from within and outside the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). While his statement has infuriated some, the Dalit community in Uttar Pradesh has worn it like a mockingly self-aware band of redemption. The political saga is surface-level, limiting itself to jabs and counter-punches that only cause embarrassment. However, this attempt to place Hanuman within a category comes across as all the more bewildering if you view the collection of late artist KC Aryan, which is part of the exhibition Hanuman: The Divine Simian. Aryan, an artist himself, began collecting artefacts related to Hanuman in the 50s. “His interest in and fascination with folk and tribal arts was inherent, deep down, going back to his childhood years. He was instinctively drawn to objects of folk and tribal flavour. What compelled him to collect these artefacts was the idea that they would disappear and get irretrievably lost,” Suhasini Aryan, the daughter of the late artist says. The artefacts on display date as far back as the 17th century, with a few even older. The artworks, whether it is the paintings or brass icons, have been retrieved from different corners of the country. “He collected images of Hanuman during his travels and they reached him automatically through diverse sources. Persons unknown to him came to sell bronze icons and paintings,” Aryan says. [caption id=“attachment_5731761” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

All photographs courtesy of the Museum of Folk and Tribal Art/IGNCA[/caption] Building a collection as vast and varied must have been a challenge. “He travelled across India to photograph the Hanuman images consecrated in the temples, big and small. He faced problems in most places, as the temple priests and other locals did not let him photograph them. I recollect this happened in Bhilwara in Rajasthan, and after that, in the Sankatmochan temple in Varanasi. But things found a way of working out for him. For example, a local person obtained the photograph of the Panchmukhi Hanuman in Bhilwara somehow and mailed it to my father, much to his surprise,” Aryan says. A number of textiles, artworks from Raja Ravi Varma’s press, and folk paintings that go back centuries in some cases, showcase different facets of the monkey god, from fearsome types of gait to five-headed incarnations. The interpretations and presentations are as varied a spectrum of ideas as is possible to imagine. As to just why Hanuman seems to have travelled as a character out of folklore rather than the Ramayana, Aryan offers an explanation. “Hanuman’s popularity is mainly on account of the Ramayana. This epic has countless versions popular within our country, some of which travelled across the frontiers to Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia. Their interpretations of Hanuman were in accordance with the Ramayana versions that travelled there,” she says. “Some of the most influential saints in the 20th century, such as Neem Karoli Baba and others like him, were great devotees of Hanuman. They set up his temples in different places within the country and abroad. In the course of the past five or six centuries, the Ramanandi saints from South India played a vital role in popularising the cult of his five-headed images all over the country.”

All photographs courtesy of the Museum of Folk and Tribal Art/IGNCA[/caption] Building a collection as vast and varied must have been a challenge. “He travelled across India to photograph the Hanuman images consecrated in the temples, big and small. He faced problems in most places, as the temple priests and other locals did not let him photograph them. I recollect this happened in Bhilwara in Rajasthan, and after that, in the Sankatmochan temple in Varanasi. But things found a way of working out for him. For example, a local person obtained the photograph of the Panchmukhi Hanuman in Bhilwara somehow and mailed it to my father, much to his surprise,” Aryan says. A number of textiles, artworks from Raja Ravi Varma’s press, and folk paintings that go back centuries in some cases, showcase different facets of the monkey god, from fearsome types of gait to five-headed incarnations. The interpretations and presentations are as varied a spectrum of ideas as is possible to imagine. As to just why Hanuman seems to have travelled as a character out of folklore rather than the Ramayana, Aryan offers an explanation. “Hanuman’s popularity is mainly on account of the Ramayana. This epic has countless versions popular within our country, some of which travelled across the frontiers to Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia. Their interpretations of Hanuman were in accordance with the Ramayana versions that travelled there,” she says. “Some of the most influential saints in the 20th century, such as Neem Karoli Baba and others like him, were great devotees of Hanuman. They set up his temples in different places within the country and abroad. In the course of the past five or six centuries, the Ramanandi saints from South India played a vital role in popularising the cult of his five-headed images all over the country.”

Hanuman beyond labels: Amid debate over his caste, an exhibition showcases monkey god's diverse forms

Manik Sharma

• December 17, 2018, 09:40:54 IST

The collection of late artist KC Aryan, which is part of the exhibition Hanuman: The Divine Simian, features images of Hanuman in textiles, paintings and photographs

Advertisement

)

Fables about Hanuman — of him carrying mountains or cutting open his chest to reveal the presence of Ram — are common to households in India. “Folk artists, as you can see in the exhibition, did not deviate from the basic iconography. The differences are stylistic – the folk images are far more simplified; the sophistication, the greater finesse, greater attention to details, better finish seen in courtly style paintings are not discernible in folk art/images,” Aryan says. The artistic flourish to each piece is unique, telling a story that needs to be read on its own. Naturally, Aryan believes that the recent statements that have unexpectedly thrust Hanuman into debates over identity and origins, are misguided. “No mention of his caste exists anywhere in the Ramayana. He was not a Dalit. He wears a janeu/yajnopavita, according to Tulsidas,” she says. Aryan further stresses that Hanuman exists in Indian culture in multiple forms, often guided by the subjectivity of perception, which is also how he is best understood. “In later centuries, that is, during the medieval period, his one-headed, five-headed, seven-headed, eleven-headed forms found favour with Tantric priests, for attaining spiritual powers. All these manifestations are portrayed in paintings and sculptures across India, from where they travelled to Nepal,” she says. But in times when identity carries not just privilege but mileage as well, can theory and theatrics combine to blur divinity to the point where even Hanuman becomes a political derivative? “No, it is not possible to categorise him. Even in the Ramayana, he assumes so many diverse forms. His presence in Indian culture is vast and varied,” Aryan says. The exhibition is on display at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts, Delhi (IGNCA)

End of Article