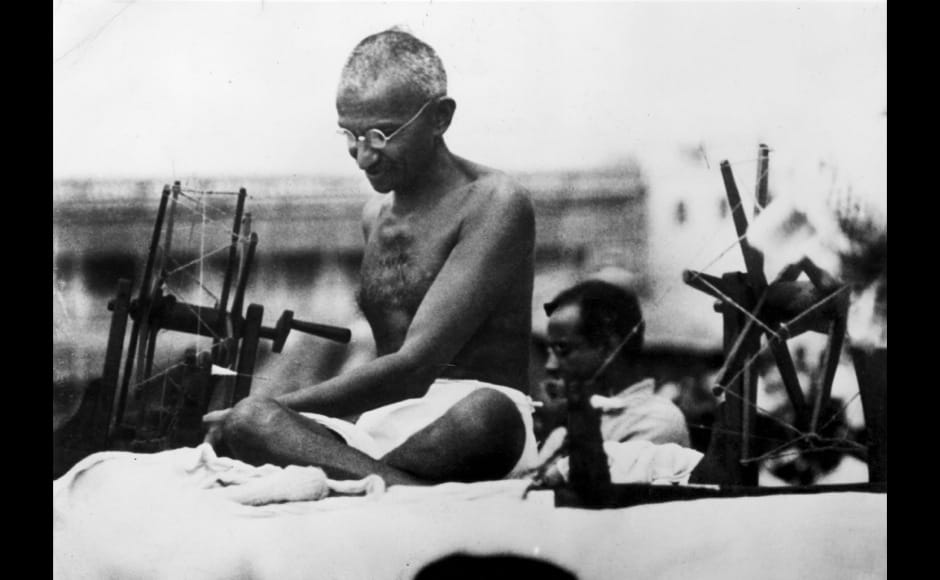

How much can you transform yourself? How much can you change from within, on your own – without any aid from any external agency, like a guru? Mahatma Gandhi is arguably the only individual, after the Buddha, who provides a measure of man’s potential to cultivate a rich inner life and attain self-transformation. Gandhi is a man of many parts: mass leader, social reformer, visionary politician and so on. He is also a model for self-formation. If you are looking for ways to change your life, Gandhi can provide you a few useful tips. “To say that perfection is not attainable on this earth is to deny God,” he writes to Esther Faering, a Danish missionary with whom he had a long correspondence. In the midst of the Champaran satyagraha, he found time to pen this missive from Motihari on 13 January, 1918: “We do see constantly men becoming better under effort and discipline. There is no occasion for limiting the capacity for improvement.” He is echoing one of his favourite authors, Henry David Thoreau, who writes in Walden: “If one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.” [caption id=“attachment_1740399” align=“alignnone” width=“940”]  Mahatma Gandhi. File image[/caption] So, “effort and discipline” turned the shy, diffident youth (with much to be diffident about) who landed in Durban in 1893 into the accomplished visionary with radical ways and mass following and the epithet of ‘Mahatma’, who arrived in Bombay in 1915. For those seeking change from within, it is easier to identify with Mohandas in his 20s – not much different from you and me – than to take as models those messiahs and messengers who claim to be already ‘chosen’ and thus did not have to face inner resistance that we have to. If we wish to explore his path beyond “effort and discipline”, we can follow his commendation of the Bhagavad Gita as his spiritual diagnostic tool (‘nidan granth’), or dip into the Bible which helped him in South Africa to put together his moral framework, and follow him onward in his eclectic mixing of religious and spiritual traditions – a journey well put together by JTF Jordens in Gandhi’s Religion: A Homespun Shawl (Indian edition: OUP, 2012). For a serious seeker of transformation, however, the challenge is ‘how’. We read the Gita (usually in English translation like Gandhi first did); evangelically distribute copies of the Bible, or gift the Dhammapadas to friends, hoping their life would be immediately changed for the better after turning the last page. But sacred books have been sitting on shelves for ages with their wisdom intact: unless we learn how to read them, and more importantly how to put the lessons into practice, books themselves are not going to change much in the world. And it is here, in the ‘how’ part of self-formation, that Gandhi, a man not much different from us in our daily grind, can be our most helpful friend, philosopher and guide. Even in this age of viral life hacks, Gandhi’s seemingly humdrum daily practices have much depth to offer. But before that, a brief detour. In recent decades, a set of thinkers have been calling for a different conception of philosophy. Philosophy is not merely scholarly study, classroom teaching, seminars and so on – as has been the case for centuries. For the ancient Greeks and Romans (and also for ancient Indians), philosophy was a way of life. It was less a matter of textual analysis and more an exploration of the perennial question: How to live. French philosopher Pierre Hadot explains how philosophy was a mode of life, the art of living, for the ancient philosophers. “For the ancients, the mere word philo-sophia – the love of wisdom – was enough to express this conception of philosophy. (…) Philosophy was a method of spiritual progress which demanded a radical conversion and transformation of the individual’s way of being. Thus, philosophy was a way of life, both in its exercise and effort to achieve wisdom, and in its goal, wisdom itself. For real wisdom does not merely cause us to know; it makes us ‘be’ in a different way.” (Philosophy as a Way of Life: Spiritual Exercises from Socrates to Foucault, Blackwell, 1995.) As KP Shankaran, who taught philosophy at St Stephens, once pointed out, philosophy as a way of life still exists, as demonstrated by Gandhi’s life and teachings. Gandhi was alive to this aspect, as he wrote to a correspondent: “All our philosophy is dry as dust if it is not immediately translated into some act of loving service. Forget the little self in the midst of the greater you have put yourself in. You must shake yourself free from this lethargy.” The model sage of philosophy as a way of life, according to Hadot, is Socrates, who did not deliver lectures in classrooms or write any book but lived life more purposefully. Socrates was of course one of Gandhi’s heroes, in life and more so in death. One of his earliest books, a pamphlet actually, is a Gujarati paraphrase of Plato’s ‘Apology’ of Socratic speech (1908). Hadot especially points to Stoic philosophers as the true-blue practitioners of life-oriented philosophy. Gandhi read at least one book on Stoicism, as far as we can say from records, a thick volume titled Seekers After God by Frederic William Farrar, during his incarceration in Yervada (1922-24). “An inspiring book,” he noted in his diary. British philosopher Richard Sorabji writes, “It was noticed by Gandhi’s learned secretary, Mahadev Desai, that his ideals were sometimes remarkably similar to theirs [stoics’]” (Gandhi and the Stoics: Modern Experiments on Ancient Values, OUP, 2012). Following Hadot’s lead, more famous French philosopher Michel Foucault in his final years turned to the related theme of the Care of the Self. “I became more and more aware that there is in all societies, I think, (…) techniques which permit individuals to perform, by their own means, a certain number of operations on their bodies, on their own souls, on their own conduct, and this in such a way that they transform themselves, modify themselves, and reach a certain stage of perfection, of happiness, of purity, of supernatural power, and so on.” If one can’t think of Gandhi while reading these lines, here is a more explicit reference connecting the “technology of the self” with politics: “… I think we may have to suspect that we find it impossible today to constitute an ethics of the self, even though it may be an urgent, fundamental and politically indispensable task, if it is true after all that there is no first or final point of resistance to political power other than in the relationship one has to oneself.” What these parallels show is that Gandhi was as much inspired by the Gita and the Bible as by Socrates and Stoics. In Hind Swaraj, he defines true freedom, Swa-Rajya, as the self-rule in the sense of rule over the self. In his journey towards this goal, he innovated and developed many “practices of the self” which happen to resonate with ancient secular wisdom. So, can we understand Gandhi’s ‘self-practices’ or spiritual exercises in the light of the ancient wisdom? Hadot calls such practices “spiritual exercises”. His list, gleaned from ancient Western philosophers, include research (zetesis), thorough investigation (skepsis), reading (anagnosis), listening (akroasis), attention (prosoche), self-mastery (enkrateia), indifference to indifferent things, therapies of the passions, and the accomplishment of duties. In modern times, people like Leo Tolstoy, John Ruskin and Henry David Thoreau turned to such practices, and following in their footsteps was Gandhi, whose life is an example of Philosophy as the Art of Living. Writing — and writing the self Foucault says, “Writing was also important in the culture of taking care of oneself. One of the main features of taking care involved taking notes on oneself to be reread, writing treatises and letters to friends to help them, and keeping notebooks in order to reactivate for oneself the truths one needed.” In this light, the 97 volumes of the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (CWMG) is nothing less than an exercise in self-formation. Think of his correspondences, beginning with naive questions to spiritual mentor Srimad Rajachandra to his replies to various people giving detailed advice on reading the Upanishads and maintaining brahmacharya. We should also add, to the CWMG, his alter ego Mahadev Desai’s diaries running into several volumes. The autobiography is also a purely spiritual exercise for Gandhi: “I simply want to tell the story of my numerous experiments with truth, and as my life consists of nothing but those experiments, it is true that the story will take the shape of an autobiography.” (For more on this, see the introduction to the critical edition of the autobiography, prepared by Tridip Suhrud, Penguin, 2018) Notably, writing as a way of self-fashioning is not something one finds in Indian religious/spiritual tradition. Reading Citing ‘Philo’, Hadot considers reading as an exercise in itself. As with writing, Gandhi’s sadhna is inconceivable without reading: the Gita, the Bible, pamphlets…. In the autobiography, he declares three modern men (ancients not included) who influenced him most: Raychandbhai (Srimad Rajchandra), Tolstoy and Ruskin. In a letter to Premabehn Kantak in 1931, he also adds Thoreau to this list. He repeatedly claimed in letters, lectures and interviews that if his life was most dramatically changed by anything, it was by reading Ruskin’s book, Unto This Last. Friendship Hadot writes that Epicureans emphasise the role of friendship in one’s spiritual development. This puts in perspective Gandhi’s special relationship with some key companion, notably Hermann Kallenbach – the two of whom indulged in a series of spiritual exercises together. Community Hadot says, “All philosophical schools [in ancient Greece and Rome] engaged their disciples upon a new way of life, albeit in a more moderate way. The practice of spiritual exercises implied a complete reversal of received ideas: one was to renounce the false values of wealth, honors, and pleasures, and turn towards the true values of virtue, contemplation, a simple life-style, and the simple happiness of existing.” Gandhi’s ashrams seem closer to this conception of community engagement in self-practices than to those ashrams of ancient India. Among other self-practices with obvious Gandhian counterparts are taking care of the body, silence, retreat, listening to the self for the truth within (“inner voice…”), moral purification, and parrhesia (speaking truthfully, especially the ethical obligation to speak a difficult truth to the powerful). And philosophy as training for death – the art of dying. As the world witnessed on that day 71 years ago. The author is the editor of Governance Now.

Mahatma Gandhi is arguably the only individual, after the Buddha, who provides a measure of man’s potential to cultivate a rich inner life and attain self-transformation

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)