Editor’s note: This is the second article in a two-part series that examines how Muslims in and around regions near Delhi have had to significantly alter their lives following the recent riots. Read the first article here.

***

At around 11 pm last Sunday on the Delhi Metro going from Botanical Garden towards Shaheen Bagh, a man of about 50, confused, asked a young man- “Is this metro going towards Shaheen Bagh?” The young man, Shahbaz Rizwi, responded, “Yes, it is just three stations away.” Shahbaz noticed that the man was uneasy and had a scared look on his face throughout the journey. This made him interested in knowing why. He didn’t ask — but soon understood the reason. When the man got out of the train at the Jasola Vihar-Shaheen Bagh station, he took out a skull cap from the pocket of his jeans, which had been neatly folded up, and wore it on his head. That Sunday (23 February) was the first day of major violence in northeastern Delhi . Recalling the interaction with the man in the metro train, Rizwi said, “I felt pained to see that. Here was this old man, a practicing Muslim in all probability, who had to remove a part of himself to avoid any trouble. The environment in Delhi has become so hostile towards Muslims, and the recent Delhi riots have scared the community very much.” He also said that the reason for the fear among the Muslim community is also owing to the communalisation of the Shaheen Bagh protests and the threats it has been receiving from radical Hindu organisations. “It has scared not just our elders, but also the youth,” he added. Rizwi used to be a teacher of Physics at a coaching centre in the Jamia Nagar locality. Since the ‘crackdown’ on students of the Jamia Milia Islamia university by the Delhi Police on 15 December, 2019, he hasn’t been teaching his students. He says, “Most of my students are enrolled in Jamia University. I didn’t have the heart to face them.”

‘Don’t dress like a Muslim, don’t talk like a Muslim’

But not all Muslims have the privilege of putting away a noticeable part of their religious identity into their pockets. Khansa Fahad, a Jamia student, is a hijab-wearing practicing Muslim. She said, “People like me, who are visibly Muslim, have to either stay home or accept the risk that we face while stepping out.” She has been avoiding getting out of her house since the riots broke out in Delhi. [caption id=“attachment_8114241” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  A man sits behind his burnt car in Delhi’s Chand Bagh, one of the sites of the recent violence. The man’s shop (seen behind him) and his home located above it were also burnt. Ismat Ara[/caption] However, Khansa has felt the fear of facing prejudice due to her identity earlier as well. She recalled, “While applying for internships, I was worried that I will get rejected if I put my photo in my resume. Although I had worked with Rohingya refugees, I only mentioned social work with ‘underprivileged people’ in the CV. I’m always afraid of being labelled as an extremist, not just by those from the right wing, but also by the people of my own community.” The recent riots have been an eye opener for her. She adds, “Earlier, I was never bothered about these things. I have become more conscious of my identity and the systematic oppression that we had been facing for so many years.” Mehreen Fatima is a Muslim PhD scholar in the Delhi University who travels daily. She says that she has often stopped herself from saying “Allah Hafiz” or “Salaam” in public when she heard people around making anti-Muslim comments. She said, “Since I do not fit in people’s typical stereotypical image of Muslim women, I have often overheard conversations in which people were spewing venom against Muslims right in front of me. This made me stop saying ‘Salam’ or ‘Allah Hafiz’ on a call while I’m out, for fear of inviting any unwanted trouble for myself.” In the past few days, she, too, has become more conscious of her identity. She said, “Of late, I have not even been opening WhatsApp while traveling outside, as most names on the contact list are those of Muslim relatives.” She added, “Every time I mention my name to anyone, I fear that their attitude towards me will change. While it doesn’t always happen, I’m apprehensive about mentioning my name now. If it is not too necessary, I at least avoid mentioning my surname, as it is an obviously Muslim one. That is what these riots have done to us.” Recalling a recent incident from a cinema hall, she said, “We all stood up for the national anthem, and once it was over, a gang sitting in the row behind mine shouted loudly “Jai Shree Ram” and everyone was just fine with it. Is this really a secular country, where I feel unsafe saying ‘Salam’ on call, and these people openly shouted religious slogans without any fear? But then I realise, we’re on the verge of becoming a Hindu Rashtra and this veil of pseudo-secularism has already fallen.”

‘Metro ka naam Anjali, ghar ka naam Adeeba’

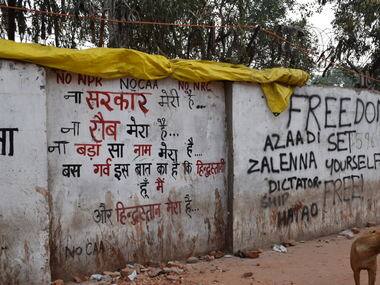

Saima Rehman, a resident of Subhadra Colony in Delhi, recalls an incident which she termed as “scarring”. Her sister, Adeeba, a school student, whispered into her ears while travelling in the Metro- “Baaji, mera Metro ka naam Anjali hai, aur ghar ka naam Adeeba.” (Baaji, my ‘name’ in the Metro is Anjali, and at home, it is Adeeba.) Saima further said, “On one occasion, Adeeba even said while responding to a call, ‘Jai Shree Ram…main metro mein hoon (I am in the Metro.)” Saima said, “We have faced Islamophobia since we were kids, in school. But to see your younger ones erase parts of their identity to safeguard themselves, that too at such a young age, is so painful. My brother, who has been an agnostic for years, prayed to Allah after the riots happened for peace.” [caption id=“attachment_8114251” align=“alignright” width=“380”]  A wall in Delhi’s Mustafabad with slogans against the CAA, NPR and NRC. Ismat Ara[/caption] Saima lives in a Hindu dominated area, and her father had kept the house locked for three days since the riots started. She said, “My father always used to believe that being in a mixed population was best for kids. But now his faith in his neighbours, who he has known for fifteen years, is wavering. He is finally thinking of paying heed to the suggestions of his friends and family- to move into a Muslim ghetto.” Hakim Afzal, a Kashmiri based in Delhi, said that many Muslims have, out of fear, not only changed their appearance, but also the way they speak. Afzal is a personal historian and had completed his post-graduation in political science from Jamia Milia Islamia in 2017. He said, “Sometimes, while speaking, people avoid greetings like ‘Salam’ or ‘Khuda Hafiz’. These days, I also have to be careful about the books I read in the Metro or other public places. I have read literature on Pakistan, but imagine what might happen if I start reading that in public - even if it is a part of my curriculum. Symbolic and pictorial representations that identify a person as belonging to a minority group become a source of threat that community in a situation of conflict. I might even have to be fearful of sneezing in public, because inadvertently what comes out of my mouth after I sneeze is ‘Alhamdulillah’.” Talking about the need to change appearances, he added, “It is all about ‘not appearing like a Muslim’ in the present context. Recently, I got a phone call from my family back in Kashmir. They asked me to get a clean shave so that people don’t identify me as a Muslim in general and a Kashmiri Muslim in particular. As it is, there are layers to the threat we all face and right now. Being a Kashmiri Muslim in Delhi is not the most ideal of things.” Hamza Syed, a researcher with the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, a global research centre, says that he doesn’t tell his name to people unless he is specially asked to. “My work requires me to travel to a lot of places and interact with a lot of government officials as well as farmers, etc. There is a clear change in their tone once they find out that I’m a Muslim, so I tend to avoid that as far as possible. If I’m getting a call from home or from a relative in a public place, I normally try to get out of the place I am in before I pick it up. Sometimes, I don’t pick up the call so I don’t have to greet them with a ‘salaam’,” he says.

Cab drivers refuse Muslim customers

Abu Sufiyan, founder of Purani Dilliwaalon ki baatein, a collective that tells stories of residents of Delhi, says, “I have made some major changes in my Uber app since the riots. Firstly, I have changed my name on the app and put the name of my company. Since I have done that, my rides don’t usually get cancelled. Secondly, I have started to put in the pick and drop location as Kasturba Gandhi hospital in Daryaganj instead of Jama Masjid. Even though they are just next to each other, Jama Masjid rides get cancelled while Kasturba Gandhi hospital ones get accepted.” Sufiyan lives in the interiors of Old Delhi. He says he changed his name on Uber because he once booked a cab and told the driver to go to Jama Masjid, but the driver refused. After a verbal spat, Sufiyan had to cancel the ride and take another cab. He recalls, “The driver was paranoid about going into a Muslim-dominated area. These people are made to believe that such localities are prone to riots and thefts, although nothing of the sort happens.” [caption id=“attachment_8114231” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  A group of people in Mustafabad, one of the riot-affected localities in northeast Delhi. Ismat Ara[/caption] Asia Ikram, a Jamia student also spoke about the difficulty of finding cabs during anti-CAA protests in Jamia. She said, “It’s nearly impossible to get a cab back to Jamia from literally anywhere in Delhi. Even when I did get it once, the cab driver went on talking about the ‘gundas’ in the area, and that he is armed to take care of them. He had a baseball bat. I had to nod along till I reached. It was really scary.” But some people have worked out ways around this issue. Daud Arif is an activist who works in GTB Nagar, close to the riot-affected areas in North East Delhi. His name on Uber, however, is Ankit Singh. He justifies it by saying, “Since the time that we have been working near GTB Nagar, we have changed our names on Uber, so that our identity is hidden when we move to and fro. It’s scary.” The recent riots in Delhi and the demonisation of a certain community has resulted in a nationwide sentiment of hatred towards Muslims. An engineer based in Bangalore, has made a list of things which he calls “An Essential Guide to Surviving in India as a Muslim.” Among the pieces of advice in the list are — “Never participate in political discussions in office or add people from your office to your Facebook list. When in north India, think twice before telling your name to anyone. Drop the habit of enthusiastically getting in a conversation with the cab or auto driver — just put on your earphones. Be careful in sharing things on Facebook, because school and college friends will unfriend and block you for your political opinions.” He said, “It is extremely common to approach a group or people discussing politics and see them change the topic once you get there. Either their volume goes completely down or they change the topic immediately.”

Journalists, activists recount challenges

Ruba Ansari, a reporter at Hind News, a Hindi news portal, said, “On the night of 23 February, I received news that Muslims had been specifically targeted in the riots. At that time, I didn’t pay heed to it and I thought it was an exaggeration. But once I actually went there to report and saw the hostile environment there, I realised that it was true. I was not allowed to use my camera. People were openly chanting ‘Mullon ko kaata jayega’ (Kill the mullahs), even in front of the police.” According to her, her cameraperson, a man named Aamir Tyagi told people in the area that his name was Amit Tyagi to avoid being attacked. “As for me, I was anyway wearing a bindi, due to which people assumed I’m a Hindu,” she remarked. Sabika Abbas Naqvi, a poet as well as a social activist, has been active in relief work in the riot-affected areas of northeast Delhi. She said, “While going to Maujpur for relief-related work, I wore a bindi.” But she didn’t wear the bindi as part of dressing up. She explains, “A bindi is something I wear only when I dress up. On this occasion, I wore it to hide my identity.”

Being atheist doesn’t help

Wamique Gajdhar, an AIIMS doctor says, “I am a staunch atheist, but I’ve faced a lot of hostility just for having a Muslim name. Even my good friends always take my views with a caveat, as they think I have sympathies for fundamentalists.” Talking about issues while house-hunting, he said, “Recently, I was searching for a home, and the broker told me not many people are willing to give homes for rent to Muslims.”

Concerns about mental well-being

Afiya Mohommad, a therapist, said, “The most important bit in cases of human-made disasters such as riots is to secure people’s health and wealth. Once immediate physical safety is secured, crisis intervention should be given to them immediately.” According to her, Muslim clients mostly have issues of security. She says, “My Muslim clients have a tendency of being insecure and have a constant fear of being attacked.” Talking about the clients she is dealing with currently, she said, “Most of my patients have been volunteers who have been working on ground during the Delhi riots. They absorb all the grief around them. So, the major problems they face are grief and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.” She suggested play and group therapy for relief, the distraction of kids, and long-term psychological treatment of adult victims. She says, victims of riots are prone to have nightmares. “There are chances of nightmares, sleep terror and paranoia.”

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)