Editor’s Note: In this eighteen-part series, we will attempt to address the tropes associated with the communities in question from an Adivasi perspective while also exploring the contemporary relationship of Adivasi citizens with the Indian government. This is the the second part of the sixteenth article of the series on Adivasi communities in peninsular India.

***

The following is a compilation of personal narratives of adivasi students, where they speak about how they view their educational journey and their interactions with non-adivasi communities while pursuing education.

***

Roshan Oraon

I hail from Chalouni Tea Garden, Dooars, North Bengal. Currently I am pursuing MA in Education from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. In my native place, there are government as well as private schools. However, one can only study till Class 8 there. To study in Class 9 and 10, children have to travel for ten to fifteen kilometres. For Class 11 and Class 12, they have to travel for a further 30 kilometres. My parents work in the tea garden as daily wage labourers. With the limited income, pursuing education was not an easy journey for me. My parents worked hard so that they could send me to a private school which had a relatively low fee. Though the medium of instruction was English, teachers taught in Hindi, Bengali or Nepali. I had to struggle, as did many others, because of the sudden change in language. At home, we speak in indigenous languages such as Sadri. At this school, none of the teachers had a B.Ed degree. I studied here till Class 8. At the time when I cleared Class 8, my elder sister cleared her Class 10 examination. Till date, there is no avenue for further studies in my area. It was difficult for my parents to find a school for my sister. The major constraint was that of financing. If my sister was to take admission in Class 11, it would mean staying in a hostel. This would entail an additional expense for my parents. It was then that I decided to take a break from education and work so as to be able to support my sister’s education. At that point of time, there seemed to be no other way. I went to Bengaluru, and worked at a restaurant to support my family. After a year, my father asked me to come back and continue with my education. Subsequently, I left the job and took admission in the National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS). [caption id=“attachment_7364121” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Members of Prayatn, a community support collective. Roshan Oraon[/caption] While pursuing my education, I started teaching children in my own village. I had the desire to contribute to the well-being of my own community but I did not know how I should do so. It is then — and I feel it was destiny — that I met a person who helped and guided me. I started working along with him on the pressing issues in my village and in neighbouring tea gardens. We started working to promote education in the region. We conducted a survey to ascertain the dropout rate in the region and also the ways to promote education. In the survey, we found that like me, many people had opted out of education because of multiple reasons. While one reason was that of finances, another reason was that the adivasi communities in the tea gardens were kept in the dark about their constitutional rights with respect to education. Also, many youths were not aware of the so-called elite institutions like JNU, TISS, Delhi University, Azim Premji University, Jadavpur University etc. Then, we as a group started with our movement in the tea gardens to promote education amongst children and youth. We named our group as ‘Prayatn’. The year 2014 brought great joy for us, as a youth from the Chalouni tea garden, Ajay secured admission in TISS, Guwahati. This had a ripple effect in our area Our group continued to strive towards promoting education in the region. All this while, I continued my education through NIOS. I completed my Class 12 and graduation and last year, I applied for admission to TISS, Mumbai. Getting admission in MA (Education) in TISS, Mumbai was a dream come true. And it is the result of the cumulative effort put in by my parents, sister, my community and the group ‘Prayatn’.

Irma Kerketta

In 1999, when I was 12 years old, I heard a classmate of mine exclaim with surprise, “Adivasi gaadi chalata hai! (Look, this adivasi person drives a vehicle).” This remark changed my outlook towards life. Due to it, I began thinking about what it means to be an adivasi. I began to wonder — do adivasis constitute a different species, or do they have different physical features? I saw that adivasis looked like other human beings. I then wondered if the distinctive feature was the darker skin tone that some adivasis have. I often heard the term ‘adivasi’ from my parents, who would always speak about helping the community. I wondered why they always spoke about helping them in particular, not knowing that I was one of them. [caption id=“attachment_7364131” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A field at Konmenjra, Kumhar Toli, Simdega. This is where I belong. Irma Kerketta[/caption] I come from a lower middle class environment, and I have grown up seeing my parents take care of not just my family, but also my uncles and aunts. I saw that they tried to help our extended family in whichever way they could. Although my parents are not very educated, they have always believed that education ensures a better life. After my mother would come back from work, she would help my brother and I as we completed our homework. She would also cook, wash clothes and clean the house. My father worked in a different state, and only visited home twice a year, during Christmas and Easter Holidays. I now know how hard my parents worked to ensure that I got educated. I was a below average student. While my mother helped me with my studies till Class 6, after that, it was very difficult for me to cope with science subjects. Teachers favoured students who performed well and had good grades. Such students were made the heads of the sports team, cultural team, etc. This created a gap between the high-scoring students and the others. Nobody seemed to bother about those who did not score good marks, like me. I remember how one of my teachers never failed to taunt me and my brother in class as well as outside. He would make fun of adivasi students, and would pass comments on what they eat and how they look. I wonder now if I should call him a teacher, in the real sense of the term. However, I cannot deny the fact that there were some teachers who really cared for students like me. My parents had never dreamt big, and they never compared me with other students. They never said that I should become a doctor or engineer. All they said was that we should study hard, or else we would end up tending cows in the village. However, even if adivasis get an education, get a good job, build a good house and own a car or a bike, the non-adivasi society will always look down upon them. Such people will never fail to comment on your status and your identity. I have struggled to create my own space among them, because most of my classmates held such attitudes. My struggle as an adivasi began with engagement with non-adivasi communities. It led me to think deeply about my own identity.

Ritu Kongari

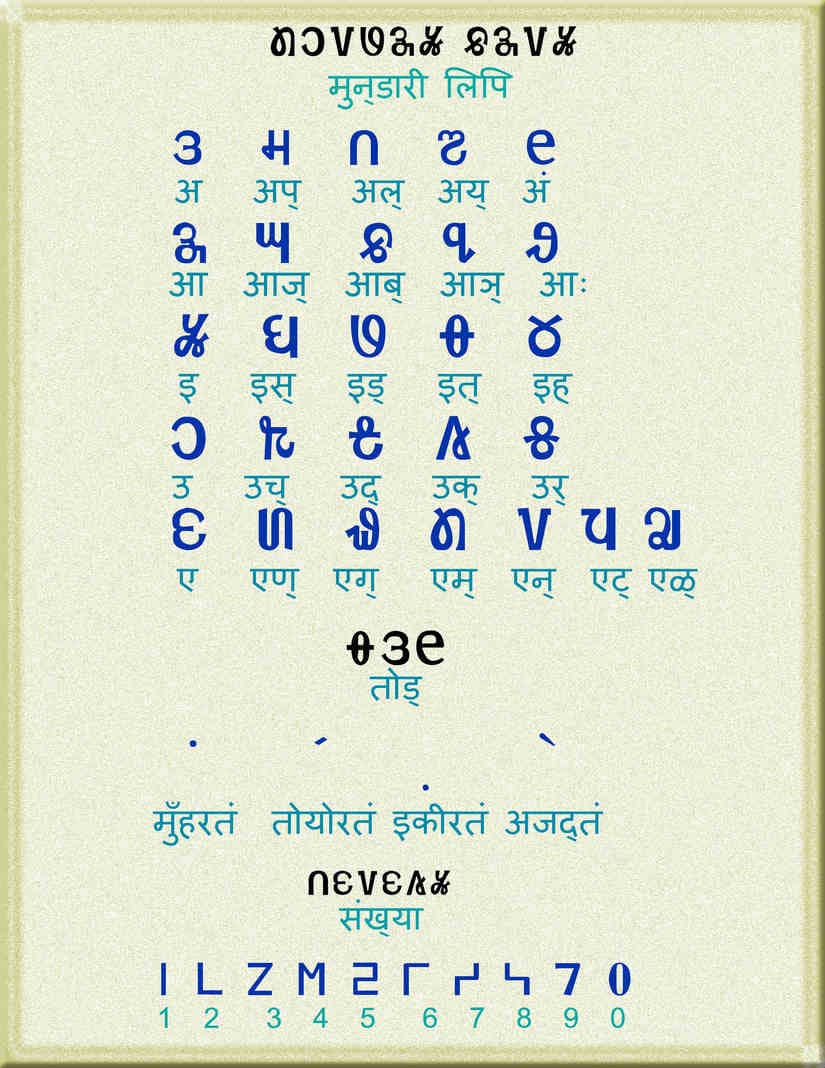

Education serves as a tool to acquire knowledge which inculcates in us the intellectual and moral characteristics that help us to unravel the underlying realities of the world. Although education can be perceived as something external i.e. outside of the being, it is internalised by the individual, due to the control exercised by the social situation. In fact, even access to educational institutions is subject to our social and geographical locations, which, in turn, is guided by the individual’s specific historical context. I am an adivasi woman from Jamshedpur. I consider myself privileged as my geographical location gave me access to education. I studied in an English medium school. My own experience with educational institutions leads me to believe that we have to settle for what is given to us. The structure of our educational institutions is such that despite the presence of the rich cultural storage of adivasi languages, we have to identify a “dominant” language. In my case, that language was English. The pursuit of knowledge, and the need to keep up with a globalized world have, in a way, robbed me of my own language and culture. I can recite poems in English but I cannot do so in my mother tongue ‘Mundari’. I can understand Mundari but I fumble when I try to speak in the language. However, by the time I realised this, I had already internalised the dominant language. [caption id=“attachment_7364181” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Mundari Bani, the script in which Mundari language is written, was developed by Olguru Rohidas Singh. Ritu Kongari[/caption] The formal educational system also conveniently excludes adivasi stories, culture, history and knowledge systems. For instance, Santhal Hul, or the history of how the Khadiya tribe fought the Diku invaders, never found space in the education curriculum. Consequently, formal education alienated me from my own culture, community and language. On one hand, this beautiful tool of education is truly equipping me to stay connected to the larger world. However, at the same time, it is also dismantling the foundations of my identity in a gradual process.

Abhishek Kindo

“New kid in Town There’s talk on the street, it sounds so familiar. Great expectations, everybody’s watching you.” (Eagles (1976), New Kid in Town) I started my education journey with no tags and no labels. Like every other kid, there were tears in my eyes when I went to school for the first time. School life was like a ‘tabula rasa,’ as I began learning language and numbers. Being a believer from a Christian family, going to a convent school suited me. Several memories from that time come to mind every now and then, and they still remain fresh. However, when I was in Class 7, I changed my school, and joined another missionary institution. My memories from my matriculation year are of lessons in bike riding and playing the guitar. As far as academics was concerned, I was awful at mathematics. Despite this, I opted for science and mathematics in my intermediate studies. My experience of studies at this level also continued to be horrible. Things took a turn for the better when I later took up arts, and enrolled in an English (Honours) course. This helped me gain a better understanding of human civilisation, society, cultural markers, and also my own existence. I began becoming more aware about my identity as a believer in God and a tribal. I then started to think about ways in which my community could find representation. In our society, only some communities traditionally had the monopoly over knowledge, and this has left tribal communities marginalised. Consequently, the voices of tribals often go unheard.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)