Editor’s Note: In this eighteen-part series, we will attempt to address the tropes associated with the communities in question from an Adivasi perspective while also exploring the contemporary relationship of Adivasi citizens with the Indian government. This is the the seventeenth article of the series on Adivasi communities in peninsular India.

***

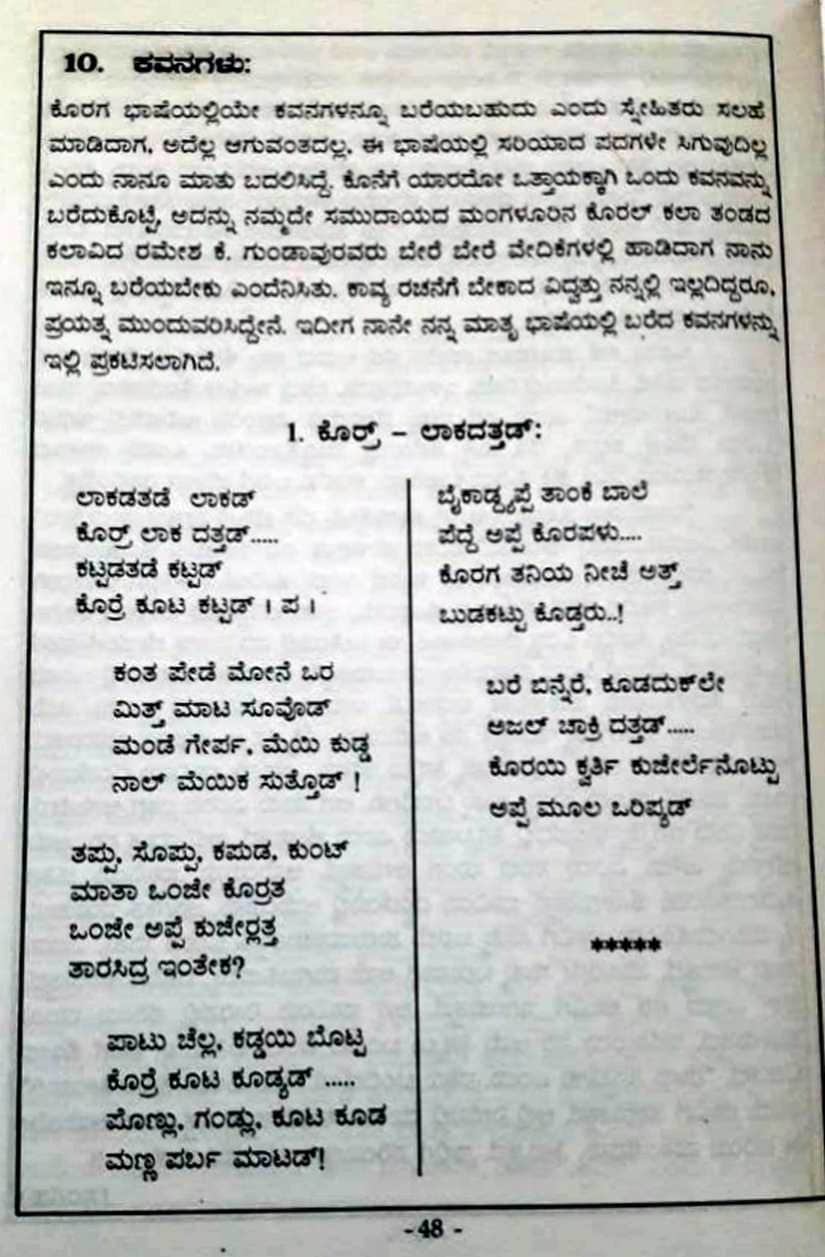

The Linguistic Survey of India, 1921 compiled by George Abraham Grierson lists ‘Koraga’ as “A secret Dravidian language of Madras. Probably a dialect of Tulu.” George Abraham Grierson was wrong. Koragas are a tribal people who live in Dakshin Kannada (DK) and Udupi districts of Karnataka and Kasargod district of Kerala, which is erstwhile South Kanara, popularly referred to as Karavali or Tulu Nadu. The language they speak is also called Koraga. It is an independent language by itself and is not a dialect of the locally spoken common tongue, Tulu. The Koragas are classified as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG). Out of the 23 lakh people who reside in DK and Udupi Districts, only 14,794 speak the language of Koraga. That is the total Koraga population (2011 population census) which has decreased substantially in the past few decades. Koraga language doesn’t have a Sahitya Academy, or a centre for development of the language or even a sub department under an existing language centre in the district, be it Tulu or Kannada. Not even a handful of non-Koragas speak Koraga. ——————— Korr, Laakadatthad Koraga, arise (This is a poem written in Koraga language by Babu Pangala, a writer and poet. There are very limited works in Koraga language and those that are there, like this poem, are written using the Kannada script. It has been translated and republished, with the permission of the poet.) [caption id=“attachment_7371561” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Babu Pangala’s poem. Image procured by Greeshma Kuthar[/caption] Laakadatthade laakad Korr laaka daththad Kattada tade kattad Korre koota kattad Getup now, get up Koragas arise and stand Let us organise Let the Koraga organise Kanta pede mone vora Mitt maata Soovod Mande Gerpa, maeyii kudda Naal maeyika suttod! The head that is bowing down s__hould look up With head held high_, shaking off your body_ t__urn in all (four) directions Kappu, Soppu, Kappuda, Kuntu Maata onje korata Onje appe kujerlata Tara sidra inteka? Kappu, Soppu, Kappuda and Kuntu (different Koraga sub sects) They are all the same Koragas All are children of one mother, then why differentiate? Paatu chella, kaddayi botta Korre koota koodyad Ponlu gandlu koota kooda. Manna parba maatad! S__inging songs, beating the drums, Koraga__s should organise Men and women come together, commemorate the Land struggle* Bykaddi appe tanke baale Pedde appe korapalu Koraga taniya neechae ath Budakattu kodtaru Bykaadi, the mother who raised the child Korapa__lu, the mother who gave birth Koraga Thaniya is not a lowlife, h__e is our Headman/C__hief Bare binnaerae, koodadakulaee Ajal chakri dattad Korayi kvarti kujaerlaenoottu Appae moola oripyad Welcome arriving guests, and gathered ones Ajal practises must stop** Wife and husband along with children, s__hould continue matrilineage (*referring to the annual festival/habba on August 18th, to commemorate the first land struggle in 1993 **prohibited in 2000 by an Act passed by the Karnataka Legislature, ‘Ajal’ are a set of inhuman and discriminatory practises forced on Koragas by Hindu society) Babu Pangala had to go an extra mile to help this reporter translate this poem. While Koragas speak Tulu and Kannada, there are hardly any non-Koraga speakers in South Kanara who speak Koraga. This is not only because the population of the Koraga community is less. There is stigma associated with the language. “Many from the community, especially those who’ve migrated to urban spaces prefer not to speak the language as this serves as an indicator of our identity,” explains Babu Pangala. Babu Pangala’s mentor and inspiration Gokul Das, a legend in DK, has a different take. He first loudly proclaims, “If we want a language to remain, it will remain. It will grow. Or else it won’t. We need to have self-respect to preserve our language.” “Nobody, be it the government or society, recognised our language. Recognition is central to the development of a language, isn’t it?” he questions. After a pause, he continues, “We look at language in comparison with value. If it seems like the language has no value, nobody wants to speak it or improve it.” [caption id=“attachment_7371571” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Gokul Das at a 1999 meeting of the Okutta. Image procured by Greeshma Kuthar[/caption] Gokul Das, born in 1935 in a small village in Karkala, rose to become one of the first leaders of the Koragas in DK. He led a struggle in the 1990s, demanding an end to all the inhuman practices that the Koraga community is made to do, termed as ‘Ajal’. In lieu, he demanded that the Karnataka government allot land to provide means for the community to ground itself. The reason for this was that the Koraga community was constantly pushed around by the administration, which viewed them as encroachers. They wanted to create a base for the community, with land being central to such a base. More than 1,000 people carried out a march, the first of its kind, starting from Boutagudde to the office of the Zila Parishad in DK in 1993. A startled district administration formed a one-man committee to pacify the Koragas. Dr Mohammed Peer was entrusted with the responsibility of speaking with the community and listing what needs to be done. After conducting interviews in 113 Koraga settlements and 407 households, Dr Peer released an eleven-chapter report titled “Social Economic and Educational Conditions of Koragas - An Action Plan.” The crux of the report was that “the Koragas are regarded as the lowest among the backward castes” (Koragas are a tribe, not a caste), “majority of them are engaged in menial and low paid occupations like basket making”, “members of other castes visit Koraga settlements only to invite them for performing Ajal duties” and “modernisation and industrialisation have not helped them improve their social status.” Dr Peer also brought to the fore that funds set aside for the welfare of Scheduled Tribes were being misused, most often for constructing roads and buildings in areas not inhabited by them. He stated that one of the main reasons for the failure of programmes initiated for Koragas was zero effort to understand their “problems, requirement and socio-cultural situation.” He concluded his report by calling upon the government to allot 2.5 acres of land on a per family basis to the Koraga community along with resettlement support, and to plan extensive programmes for their education and employment. Mohammed Peer has passed away. It has been 25 years since the findings were published. The findings of the committee are far from full implementation, even though the tribe in question is so small. The report is still being quoted by Koraga activists but it continues to languish. When I ask Gokul Das what it was like to organise at a time when there was widespread, open discrimination against the Koragas, he offers a broad smile, a smile I get accustomed to over my meetings with him. “We faced antagonism yes, but there were people such as Devdas Shetty who provided us support to organise. We formed the Koraga Abhivridhi Sanghagala Okutta soon after, which has been a source of support and strength for all of us since its formation,” he says. The Okutta was formed to represent the Koraga voice jointly in Karnataka and Kerala. The Okutta has since been leading various struggles, from demands to implement the Peer Committee Report to regular programmes against continued illegal Ajal practices. —————————————————————————— The onset of the Monsoon in the Western Ghats means incessant rains. The rains seemed to mean nothing to the 200+ persons gathered outside the DC Office in Manipal. While the group huddled together under a net of umbrellas, a bunch of police officials looked on from across the road. There was nobody from the media in sight. No flag bearing members from the Right, which holds sway over DK or the Left. No ‘progressive’ crowd with rhetorical calls for justice. Just a bunch of people who in, their own words, had lost count of the times they had been there. The Udupi wing of the Koraga Abhivridhi Sanghagala Okutta had assembled there to highlight the misuse of funds being set aside for them. Susheela Kenjur, a leader from the Okutta mentions that after continuous agitation, Rs 2.2 crore was set aside in Udupi district, “What happened to the money? It was either missed or spent on programmes which are of no use to us. Why can’t they ask us what we want?” [caption id=“attachment_7371621” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Protests in front of the Manipal DC office. Images procured by Greeshma Kuthar[/caption] Puthran, another representative explains, “They started a support scheme for pursuing a fish and chicken business. They gave us fish/chicken carts and nets. Firstly, we don’t have expertise in either of the businesses. What is the point of this scheme without handholding? Secondly, even those who struggled and used the scheme couldn’t sell their wares. No non-Koraga bought fish or chicken from us. How is this scheme supposed to help us?” This mismanagement of funds through schemes which are of no benefit to the Koragas, according to Puthran, is the biggest obstacle they’ve been fighting recently. “We ask for land, we get kotta pikas (shovel and pickaxe), if we ask for food, they give us a plate, if we ask for water, they give us a bucket, if we ask for safety from forest guards who trouble us, they give us a knife. If we ask for things we need, we are given what is of no use. It has gone to the extent that we say ‘please, we don’t want this’, and yet, government officials have forcibly shoved these things down our throat. For example, cows were tied to our yards, water pumps were left at our houses. What should we do with that cow? Or water pump? They take a photo and that’s it. This is yojana implementation for you”, says Sundar M, ex-president of the Okutta. The earliest agitation lauched by the Okutta in the 1990s had a popular slogan which said, “Surutu enkulennu therile, aayidhu bokka yojananeu korlae.” It means ‘First attempt to know us, then give us schemes.’ The slogan doesn’t seem to have had any takers from the Karnataka government, clearly. The Okutta in its letter to the newly appointed DC, IAS Hepsibha Rani Korlapati urges her to first understand the community before planning any future schemes. They also have mentioned how even after the DC approves funds, the lower officers collude to misuse or delay the disbursal or implementation. “They are also part of local caste Hindu communities which discriminate against us. Why will they do anything to help us?,” asks Susheela. The DC on her part informed me that she had already conducted inter-departmental meetings to update herself of the existing situation of the Koragas. She said that she intended to focus on education and launch efforts to tackle dropouts from schools and colleges. But since she is from Andhra Pradesh, she wasn’t aware of the extent of the stigma faced by the community. When I asked her about the illegal practice of Ajal and how she intends to take this on, she wasn’t aware of the practice. “This is another problem. Well-meaning officers take time to understand our predicament, but by the time they are aware and start working towards what we want. they are transferred out. The previous DC Priyanka Mary Francis is an example. She went from pillar to post to arrange schemes which will be of help to our women. But she has been transferred and now, we have to start from scratch,” says Susheela Nada, a social worker. —————————————————————————— Dr Sabitha, the first PhD scholar from the tribe, explains that Ajal practices are a set of inhuman and discriminatory practices forced on the Koragas. This includes offering ‘Dhana’ to Koragas, which is food mixed with hair strands and pieces of nails of sick persons or of those experiencing financial or other problems. This is done with the belief that the Koragas are a medium to get over paapa (sin) and anishta (impurities). Koragas were hence believed to be carriers of evil spirit. The above mentioned practices are just a few. There are more, which were practiced in different forms and ways. Koragas are expected to perform during temple festivals but they are expected to do so without entering the temple premises. They have to stand outside the temple and perform. For their services, they used to be paid in the form of leftover food. The Okutta started agitating for a ban against these practices in the 1990s. After continuous protests and pressure, the Karnataka government passed the Karnataka Koraga (Prohibition of Ajal Practices) Act in 2000. The Act is only two pages long, and is produced in its entirety here. Sabitha is a symbol of struggle that the Koragas face in South Kanara, to do anything at all. Hailing from Gundmi, a village in Udupi District, Sabitha had to decide which way her life should take when she lost both her parents. “I chose the path of education,” she says even though it meant a struggle against the odds of existent discriminatory Ajal practices which she saw her relatives being dragged into, or the lack of monetary support. She had to take breaks in her education so as to save money to study further. Not to be deterred, she saved enough money to pursue a college education and emerged with a Distinction in Masters of Sociology. A PhD followed soon after. Sabitha is now an Assistant Professor at the Department of Sociology, Mangalore University. [caption id=“attachment_7371641” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Sabitha in front of her Department, Mangalore University. Greeshma Kuthar[/caption] Sabitha routinely visits villages in South Kanara to interact with the community. She mentions a recent visit, where she saw how in spite of Ajal practices being outlawed, dominant castes practice it in obscure ways. “Instead of offering leftover or contaminated food outside the house, they invite people inside and do it all the same”, she says. “Some of our people still take part in it, because they fear exclusion by the village or they fear inviting the wrath of our Gods if they don’t take part,” she explains. This ‘inviting wrath of the Gods’ is what has been told to the community for centuries, to make them take part of this discriminatory practice. The Okutta has aggressively been organising programs and meetings to educate the community against giving in to the demands of the dominant castes to practice Ajal, even if it results in threats. They file FIRs whenever they can, in spite of no support from the police administration. If the practice is on the wane, the efforts of the Okutta need to be recognised for this. In fact, the Koraga community completely stopped performing in temple festivals or anywhere where they are expected to perform without remuneration or are disallowed from entering the temple premises. They formed their own group, called the Koral Kala Thanda, a ten-year-old cultural troupe which has performed across the country. Ramesh Manchakal, a senior artist of the Thanda explains that the instruments used by them can only be made by them. The skill is unique to the Koragas and so are the instruments. [caption id=“attachment_7371661” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  File image of Ramesh Manchakal. Image procured by Greeshma Kuthar[/caption] This group has also been assisting the government in imparting public messages about its outreach programmes, such as the importance of voting. This is in addition to the Thanda’s routine performances at Koraga settlements, where they educate the community against Ajal practices through cultural song and dance. [caption id=“attachment_7371671” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Koral Kala Thanda, a cultural troupe. Greeshma Kuthar[/caption] M Sundar, one of the seniormost leaders of the Okutta, has no qualms in calling a spade a spade. “After the law was passed, did the government do anything at the panchayat level to bring the Act into practice? Did any of the dominant castes who are the forefront of these practices and occupy important positions at the panchayats, share the Act with their people? Sundar says while it was the Okutta’s duty to inform its people not to take part in this inhuman caste imposed practise, he also asks an important question. “Shouldn’t it be the duty of the ones who have been the implementers of this practice for centuries, to stop their people from continuing to perform Ajal?” The question that Sundar poses is basic. Shouldn’t the onus of stopping an inhuman unconstitutional practice be on the oppressing communities? —————————————————————————— The most important demand of the Okutta has been about allotment of land. For 25 years, they’ve been agitating for land but with little success. Even the few allotments that have been made by the Karnataka government (which were 1 acre allotments, not 2.5) have been in dry, waste lands. In some cases, they were in vertical, uninhabitable lands on hills. The 2011 census puts the number of Koragas at 14,794. If one were to hypothetically consider a family of five, the number of families would roughly add up to 3,000. The Koraga community has been struggling for allotment of less than 7,500 acres of land in the twin districts of South Kanara, where a Special Economic Zone, petrochemical and other corporations, religious Hindu mutts and establishments, churches and the real estate lobby hold sway over a considerable chunk of land. This is also a district which is lauded for its land reforms in 1964, which saw landlords lose their land and tenants acquire land. The Koragas, who have historically been providing wage labour for close to no wages, got nothing out of any of this. After the Peer Committee report was released, the Okutta identified vacant government lands for allotment multiple times. “Each time we would come close to getting a grant, the panchayat officials would hamper it by coming up with false documents stating that the lands were already in someone’s name,” says Kogga Ramesh, the Vice President of the Okutta. “No non-Koraga wants to see us own land. Even if we own land, they still don’t consider us at par. I own this house. I am still not allowed in any non-Koraga house here,” says Gauri, a panchayat member of Kenjur. [caption id=“attachment_7371681” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Gauri at her residence. Greeshma Kuthar[/caption] Gauri is a household Koraga name. She was part of the Sural Chalavali in 1997 at the age of just 18, demanding land for herself and her family. The chalavali ended with promises from the government to look into the demands, resulting in nothing. In three years, she was one of the leaders at the forefront of the Kalathur Bhumi Chalavali, a fresh agitation to call out the government’s failure to act on its promise. The Kalathur Bhumi Chalavali was a one month-long paada yatra organised in 2000, demanding land for Koragas, as set out in the Peer Committee Report. It started out from Udupi and travelled throughout Udupi, ending in Kalathur at Hebri. Here, the group occupied 200 acres of reserved forest land and built 200 makeshift settlements. In less than 15 days, they were arrested, with charges of destroying forest land being foisted on them by the forest department. Twnety-seven were arrested, out of which 20 were women, 2 were children and 7 were men. Gauri was part of the arrested 27. However, the judgment in the case held that the forest officials had foisting a false case against the protesters. In spite of the arrest, a second group took over. Till 2003, the group stayed at Kalathur in spite of constant harassment from Forest Officials. The government appointed another ST officer in 2003, who led a group to physically remove the group from Kalathur. Violence ensued and many were hurt. This was followed by a 45-day strike. For the first time after this, the Karnataka government organised multiple meetings with the community. Procedures to grant land to the community started only after this. “Gauri’s outspoken attitude has crushed many casteist egos in South Kanara,” say her colleagues at the Okkuta. “The government and dominant castes patronise us often by telling us that we should change ourselves first. That we should reform before making all these demands. I tell them to hold a mirror to themselves before talking to us about what we should do.” says Gauri. She quotes the example of a temple committee of the Veerabhadra Padematta Temple in Kenjur which included a Koraga member for the first time in 2017. “On the first day, the only Brahmin who was part of the committee came to the meeting fully covered in plastic, from head to toe. A Koraga being on the committee meant pollution. There were Bunts, Billavas and Devadigas in the committee. They didn’t say a word. What reform are these people talking about?” The Koraga person in question eventually dropped out of the committee. “We have our own gods. Panjurli, Manja, Haiguli and Thaniya are our gods. Why should we even go to these spaces which treat us like this? I don’t and I also tell everybody I know not to”, questions Gauri. Gauri says she sees many changes since she started out in 1997. She feels her people are more confident now, as compared to a time when it was difficult to convince them to leave the houses of landlords who were exploiting their labour. Gauri’s vision is to create more women leaders like her, to see the land struggle reach its logical end. The most crucial part of the land struggle, according to her, is to make the government accountable for resettlement once land is allotted, as mentioned in the Peer Committee Report. —————————————————————————— The legend of Hubasika “There lived a chieftain once. He guarded the coast, from Banavasi in the north to Majeshwar in the South. His name was Hubasika. When this land came under attack, by the invading forces of Mayur Verma of the Kadamba Dynasty, he held fort. The Kadambas were driven out, beyond Manejshwar. They didn’t leave though. They plotted revenge. Lokaditya, son of Mayur Verma, invited Hubasika for peace talks with the prospect of a marital arrangement. Huabasika was trapped along with his nephew and killed. His people were driven into the forests. All of Tulunadu watched the protector of their realm lose his life. They watched outsiders ravage the lives of Hubasika’s people. As the outsiders integrated into Tulunadu, Tuluvas learnt their ways. They kept at it. They kept the brutalisation of a people going on, for centuries to come. Soon, a young Thaniya was killed in the premises of a temple. He was deified by Tuluvas and is worshipped to this day. This is the irony of the Tulu people of South Kanara. They watched as their protector, a Koraga, was killed. They deified and worshipped Thaniya, another Koraga. While continuing to discriminate against the very people who are more native to this land than them. ” The legend of Hubasika is one which is hardly told in South Kanara, though the district is known for its ancestor gods and their stories. The misrepresentation of the Koragas by non-Koraga scholars is visible in the few books which have written about Hubashika. Writers like Francis Buchanan and William Lavie, refer to Hubashika and his people as ‘chandals’ and ‘savages’. They do not once refer to the ‘savagery’ of the Kadamba dynasty, who they acknowledge of brutalising the Koragas. Further, writers like Raghavendra Rao, while writing about the Koragas and Hubashika refer to the Koragas as being a jealous people, for not offering to share their language with them, while not once acknowledging that self-preservation is a means the Koraga community had to turn to, in order to not completely disappear as a tribe. Koraga scholars like Babu Pangala mention how the only way forward to set this misinformation is for Koraga people to write their history themselves. His book on the legend of Koraga Tahniya will be soon published by the Tulu Sahitya Academy. (The story narrated above about Hubasika has been written in consultation with Babu Pangala, Ramesh Manchakal, Gauri and M Sundar.)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)